YEREVAN, Armenia (AP) — In Iran, the urgency of getting vaccinated against COVID-19 is growing by the day.

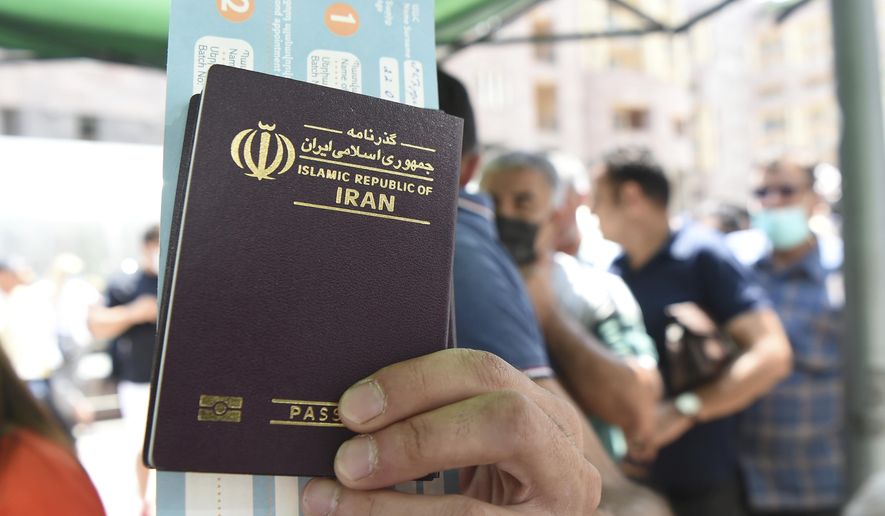

A crush of new cases fueled by the fast-spreading delta variant has threatened to overwhelm Iranian hospitals with breathless patients too numerous to handle. But as deaths mount, and the sense swells that protection for most citizens remains far-off, thousands of desperate Iranians are taking matters into their own hands: They’re flocking to neighboring Armenia.

In the ex-Soviet Caucasus nation, where vaccine uptake has remained sluggish amid widespread vaccine hesitancy, authorities have been doling out free doses to foreign visitors - a boon for Iranians afraid for their lives and sick of waiting.

“I just want her to get the jab as soon as possible,” said Ahmad Reza Bagheri, a 23-year-old jeweler at a bus stop in Tehran, gesturing to his diabetic mother who he was joining on the winding 20-hour road trip to Armenia’s capital, Yerevan.

Bagheri’s uncle had already received his first dose in the city and would soon get his second. Such stories have dominated Iranian social media in recent weeks, as hordes of Iranians head to Armenia by bus and plane. Acting Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said last week that foreigners, including residents, have accounted for up to half of about 110,000 people who were vaccinated in the country. Armenia administers AstraZeneca, Russia’s Sputnik V and China’s CoronaVac vaccines.

In Iran, which has the highest COVID-19 death toll in the Middle East, less than 2% of the country’s 84 million people have received both doses, according to the scientific publication Our World in Data.

Although the sanctions-hit country has imported some Russian and Chinese vaccines, joined the U.N.-supported COVAX program for vaccine sharing and developed three of its own vaccines, doses remain scarce. Authorities have yet to inoculate nonmedical workers and those under age 60, promising that mass vaccinations will start in September.

“I can’t wait such a long time for vaccination,” said Ali Saeedi, a 39-year-old garment trader also waiting to embark on the journey at a Tehran bus station. “Officials have delayed their plans for public vaccination many times. I’m going to Armenia to make it happen.”

Others, like 27-year-old secretary Bahareh Khanai, see the trip as an act of national service, easing the daunting inoculation task facing Iranian authorities.

It remains unclear just how many Iranians have made the trip to get vaccinated, as Armenia also remains a popular summer getaway spot. But each day, dozens of buses, taxis and flights ferry an estimated 500 Iranians across the border. Airlines have added three weekly flights from Iran to Yerevan. The cost of bus tours has doubled as thousands devise plans. Travel agents who watched the pandemic ravage their industry have seen an unprecedented surge in business.

“The number of our customers for the Armenia tour has tripled in recent weeks,” said Ahmad, the manager of a tour agency in Tehran who declined to give his last name for fear of reprisals.

The surge of Iranians has inundated Armenia’s coronavirus testing centers, leaving scores stranded in the buffer zone, Iranian semiofficial ILNA news agency reported, with several fainting from the heat. Roughly 100 miles away in Yerevan, hundreds of Iranians lined up to get a vaccine shot, with some sleeping on the streets to secure a place.

Hope sustains them through the long lines under an unforgiving sun. In the streets of the Armenian capital, Iranians cavort to Farsi music outside vaccine centers, clapping as they receive doses, videos show.

“We couldn’t expect that our humanitarian act would become popular and spread so much and that we would have a big flow of foreigners,” Armenian Health Minister Anahit Avanesyan told reporters. “Our citizens are our priority, but I repeat again that the pandemic doesn’t recognize citizenship.”

But even as Armenian authorities encourage vaccination tourism, the sheer number of Iranians flooding vaccination centers has pushed Armenia to tighten the rules.

At first, Iranian vaccine-seekers headed for clinics in the southern border town of Meghri. A local doctor, speaking to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak to the media, reported seeing at least 100 Iranians vaccinated there over the past few weeks.

But last week the government decreed that foreign visitors can only receive a jab at five designated AstraZeneca mobile clinics in Yerevan, and, in an apparent bid to boost the country’s tourist sector, must spend at least 10 days in Armenia before getting vaccinated.

Now, the profile of Iranian visitors is changing, as cross-border bus jaunts become extended vacations, with some flights routed through Qatar. The surge in interest has also pushed up the price, putting the journey out of reach for all but the wealthy.

Ethicists, who said they otherwise wouldn’t take issue with needy foreigners securing excess shots shunned by citizens, say the price hike and new 10-day requirement exacerbates the stark inequalities in the pandemic.

“It increases the money and time required … and so the inequity of who is going to be able to participate,” said Alison Bateman-House, an assistant professor of medical ethics at New York University.

More broadly, she added, vaccination vacations, like all travel in a time of contagious virus variants, carries “unintended consequences” and increases “the possibility of disease transmission.” A fairer alternative, she noted, would be for Armenia to transfer its surplus doses to the international COVAX initiative.

But for many in Iran, where scores are dying daily in an outbreak that has exhausted the health system and economy, the cost of waiting has grown too high.

Mohammad Seifpour, a 48-year-old Tehran resident, grimly surveyed the crowds of Iranians at the Yerevan vaccine clinic.

“This is just because of the horrible situation we are facing,” he said.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.