A federal judge ruled Friday that the Obama administration violated procedural laws when it created the DACA program for illegal immigrant “Dreamers,” and blocked new applications from being approved.

U.S. District Court Judge Andrew S. Hanen’s ruling could throw the issue back to Congress, where lawmakers have for decades been at a stalemate over the fate of the young adult illegal immigrants who came to the U.S. as children and are seen as the most sympathetic cases.

DACA, created in 2012, grants Dreamers a tentative stay of deportation and some taxpayer benefits, giving them a chance to embed into society, though it is not permanent legal status. The Obama administration created it through a Homeland Security memo, claiming it was exercising “prosecutorial discretion” not to pursue immigration consequences of deportation against Dreamers.

Judge Hanen ruled that was a major policy change that should have gone through the full regulatory process, and he said because it didn’t, it violated the Administrative Procedures Act.

“Accordingly, the court holds that DHS was required to undergo notice and comment rulemaking in order to adopt DACA. DHS failed to engage in the statutorily mandated process, so DACA never gained status as a legally binding policy that could impose duties or obligations,” the judge wrote.

He said the hundreds of thousands of Dreamers currently protected by DACA, officially known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, have come to rely on the protection and will continue to be protected until higher courts have a chance to review his decision.

DACA was the first of the Obama administration’s attempts at a deportation amnesty through executive action, and it was announced during the 2012 election year, as the Obama campaign team was worried about his prospects with Hispanic voters.

Two years later the Obama administration tried to expand DACA to include millions of illegal immigrants who had children who were U.S. citizens or legal residents. That program was known as Deferred Action for Parents of Americans, or DAPA. At the same time, DACA’s amnesty grant was expanded from two years to three years.

Judge Hanen blocked DAPA just before it was to take effect in early 2015. He also halted the expansion of DACA to three years.

That ruling, confirmed later by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and affirmed by an evenly divided 4-4 Supreme Court, strongly suggested DACA itself would also be illegal.

But the program has limped along for six years under that legal cloud.

President Trump attempted to phase out the program, but that attempt was declared illegal by lower courts who said the Trump team didn’t offer a good enough justification, therefore violating the APA.

That created the bizarre situation where DACA was likely in violation of the APA, but so was Mr. Trump’s attempt to erase it.

Judge Hanen’s decision reignites those court battles — but it also creates a new opportunity, and headache, for Congress.

There’s broad bipartisan support for some legalization for Dreamers, but there is disagreement over how broadly to draw it.

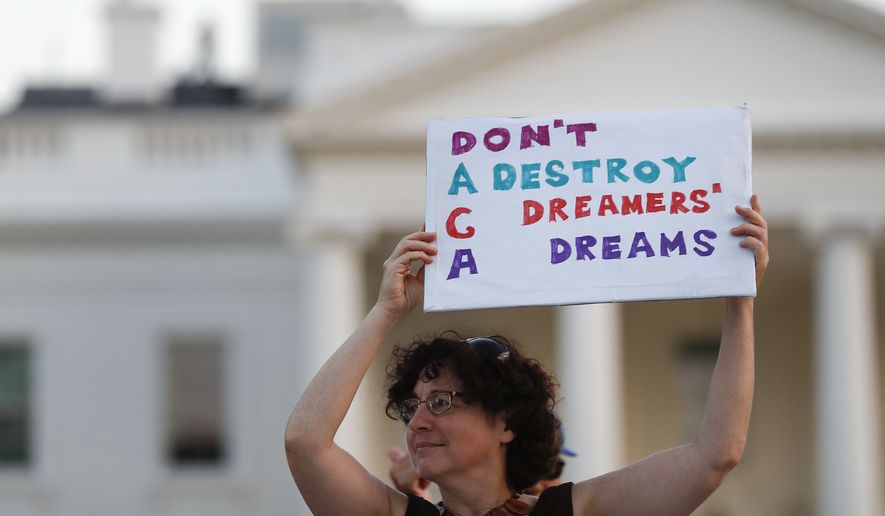

Immigrant rights activists, while complaining about Judge Hanen’s ruling, said Congress must step up with the broadest possible legalization.

“It is absolutely urgent that Congress acts now through the budget reconciliation process to provide Dreamers and other undocumented members of our communities with reliable status and a pathway to citizenship,” said Omar Jadwat, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s immigrant rights project.

Democrats have already taken steps toward that. A bill to legalize a broad class of Dreamers has already cleared the House, though it’s been declared dead by key Republicans in the Senate.

Earlier this month one of those key Republicans, Sen. John Cornyn, a Texas lawmaker who’s been involved in immigration battles for two decades, proposed a smaller bill that would only legalize DACA holders.

DACA applies to illegal immigrants who arrived before mid-2007 and had been in the country for five years, when DACA became active in 2012. The applicants were to have kept a relatively clean criminal record and to have pursued education.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.