Krish Vignarajah has been in survival mode for four years as the Trump administration slashed refugee admissions by 85%. She’s had to close a third of her resettlement agency’s 48 offices and lay off more than 120 employees, some with decades of experience.

Now, she’s scrambling to not only rehire staff but double the capacity of her Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, an expansion not seen since the agency scaled up for the wave of refugees that arrived after the fall of Saigon in 1975.

All nine U.S. resettlement agencies are experiencing the whiplash. They’re gearing up to handle 125,000 refugees this year and possibly more after that if President Joe Biden makes good on his promise to restore the number of people able to create new lives in America after fleeing persecution or war.

Agencies say they welcome the challenge after being pushed to the brink. But the last four years illustrates the need to make the 41-year-old program that’s long enjoyed bipartisan support less vulnerable to political whims if America is to regain its position as a leader in providing sanctuary for the world’s oppressed.

“We’ve seen how the sole concentration of refugee policy in the White House can wreak such destruction in the wrong hands,” Vignarajah said.

The Trump administration created so many obstacles that there are doubts whether the pipeline can rebound quickly enough to meet Biden’s expected target this year, especially during a coronavirus pandemic that has restricted the ability to safely interview refugees in camps and crowded cities.

“The foundation of the system has been so broken that to even get to 125,000 next year, there’s a big question mark,” said Jennifer Foy, vice president of U.S. programs with World Relief, a resettlement agency.

Refugee admissions are determined by the president each year, and federal funding for resettlement agencies is based on the number of people they resettle in a given year.

As president, Donald Trump targeted the refugee program under his anti-immigration policies, dropping admissions yearly until they reached a record low of 15,000 for fiscal year 2021, which started in October. Historically, the average has been 95,000 under both Republican and Democratic administrations.

The Trump administration defended the cuts as protecting American jobs during the pandemic and said it sought to have refugees settle closer to their home countries while working on solving the crises that caused them to flee.

More than 100 U.S. resettlement offices closed during Trump’s term, including eight of 27 belonging to World Relief, Foy’s agency. Its warehouses of donated household goods have grown sparse, and its relationships with hundreds of landlords have waned because almost no refugees are arriving.

The Trump administration also cut or reassigned U.S. support staff overseas who processed applications.

Despite potential problems reopening the pipeline, advocates say it’s important that Biden set this year’s ceiling at 125,000 people to start building the program back up.

He’s also vowed to seek legislation setting an annual baseline of 95,000 refugee admissions, which would help stabilize funding for resettlement agencies. Biden’s campaign said the number could go beyond that “commensurate with our responsibility, our values and the unprecedented global need.”

Biden, who co-sponsored legislation creating the refugee program in 1980, says reopening the doors to refugees is “how we will restore the soul of our nation.”

“Resettling refugees helps reunite families, enriches the fabric of America, and enhances our standing, influence and security in the world,” Biden said in June for World Refugee Day.

For decades, America admitted more refugees each year than all other countries combined, only to fall behind Canada in 2018. While the U.S. program shrank and a dozen other countries followed in shutting their doors, refugee numbers worldwide ballooned to a record 26 million because of political strife, violence and famine.

Biden has said he wants to make it easier for refugees to get to the United States by expanding efforts to register and process them abroad and making higher education visas available to those seeking safety. He’s also indicated more priority should be given to Latin Americans, especially Venezuelans whose numbers now rival Syrians among the largest group of displaced people.

Refugees already underwent more rigorous screening than any other person entering the U.S. before additional requirements under Trump slowed the process to almost a standstill, according to the International Refugee Assistance Project.

Last year, the Trump administration started requiring refugees to provide addresses dating back 10 years, a near impossible task for people living in exile.

“The Trump administration began to incorporate novel and untested techniques that overwhelmed the system with delays and dubious vetting results,” said Vignarajah, the CEO of Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service.

Still, changing that won’t be easy.

“It’s easy to ratchet it up, very difficult to ratchet it down, and that’s not to say some of those duplicative layers of vetting actually make us safer,” she said.

There are also questions about who should be at the front of the line.

The Trump administration changed the eligibility rules, setting up its own categories of who qualifies rather than using the long-standing referral system by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees that makes selections based on a person’s need to be resettled.

For instance, there was no category for people fleeing war, like Syrians.

As a result, tens of thousands of refugees conditionally approved by the Department of Homeland Security suddenly were disqualified.

Advocates want such cases to get priority.

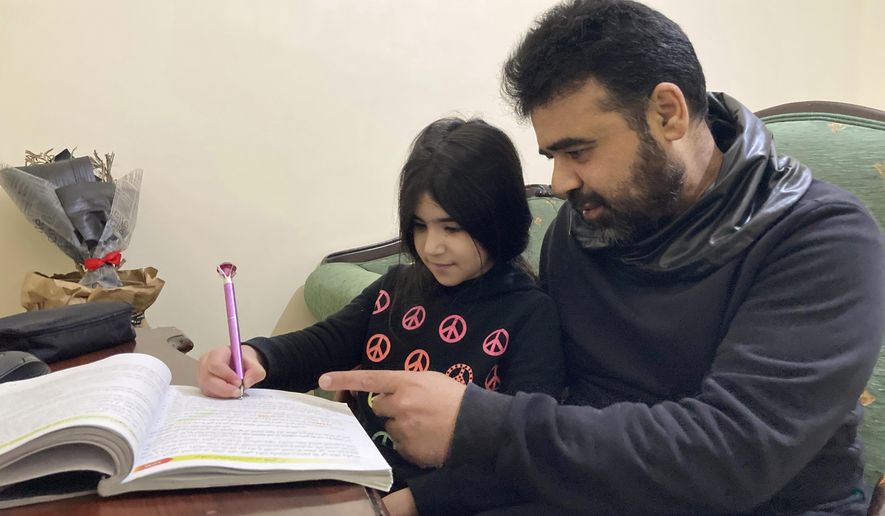

Mahmoud Mansour, who fled Syria’s civil war to Jordan, hopes to regain his spot. His family had completed the work to go to the United States when the Trump administration issued its travel ban barring people from Syria indefinitely and suspending the refugee program for 120 days.

“The past four years, during Trump’s term, our lives were ruined,” said Mansour, a tailor who has been out of work for a year and relies on help from his two brothers in the U.S. to survive. “In one moment, our dreams vanished.”

Now, Mansour feels optimistic again. The 47-year-old father said Biden sent a strong message about restoring humanitarian policies when he lifted the travel ban on his first day in office.

Mansour hopes his family will finally be reunited. And he wants the new president to know: “We will not be a burden. We will be workers there. You will benefit from us, and of course, we will benefit from you.”

___

Watson reported from San Diego. Associated Press reporter Omar Akour in Amman, Jordan, contributed to this report.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.