OPINION:

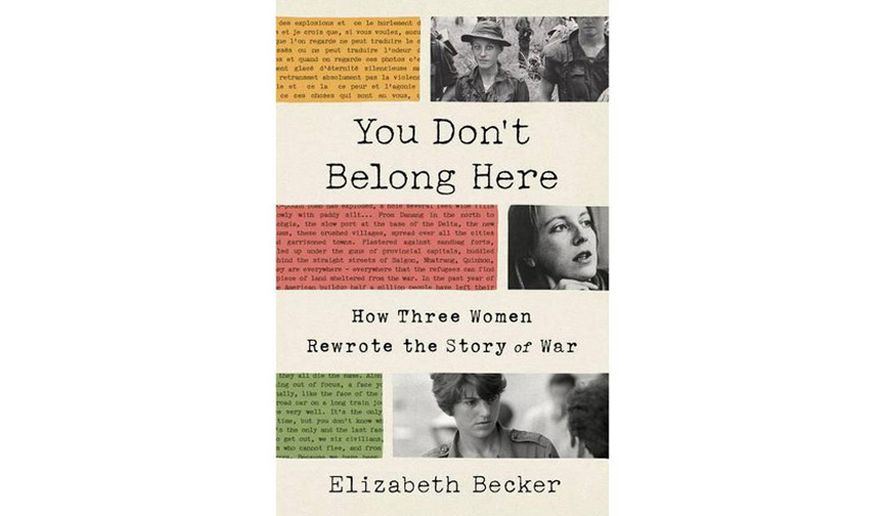

Vietnam was less quagmire and more a crucible for more than 468 women accredited reporters during a war where lives and deaths could never be measured by lines on a map. Elizabeth Becker’s new book, “You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War,” offers insightful portraits of courageous women war correspondents who helped break down stereotypes.

During the divisive and transformative 1960s, both Presidents Kennedy and Johnson offered reporters, men and women alike, unrestricted access to the first war where casualties — soldiers and the truth — were broadcast on the evening news.

The war brought professional reporters to Vietnam, but for many women it was their first job. All of them were young and many found initial employment as freelancers (stringers). President Johnson’s support, along with the U.S. State Department’s “Maximum Candor” press briefings, created opportunities for female reporters and it’s where Ms. Becker’s reporting and her experiences as a correspondent take the reader.

“We were all fixated on reporting the war that it took us decades to understand what we had accomplished as women on the front line of war,” writes Ms. Becker, an award-winning journalist and author who began her career as a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post.

The author’s selection of Kate Webb, Catherine Leroy and Frances Fitzgerald offers a personal and historical examination of women who challenged the rules imposed on them by the military, male peers, cultural and sexist barriers. I couldn’t help wondering why these three, when others like Dickey Chapelle, Gloria Emerson, Jurate Kazickas, Beverly Deepe, also distinguished themselves.

Ms. Becker’s meticulous reporting from conversations, diaries, notebooks, letters, photographs, classified military files, and their own writings, offers us new ways to see the war. There’s much to unpack in this non-linear sweep of these female reporters’ stories.

Catherine Leroy, a diminutive 21-year-old French photographer, never hesitated to jump into the fires of war becoming the first accredited journalist to parachute into Vietnam with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in “Operation Junction City” in 1967. Her photos found their way onto the pages of Life and Time, earning her many awards, including the Robert Capa Gold Medal Award for exceptional courage and enterprise; although never a steady income.

Ms. Becker skillfully threads her narrative and analysis of the impact of the heroic efforts of her subjects. Since she was also in Vietnam and Cambodia, she bears witness to the journeys these reporters made crawling, walking, slogging through rice paddies and jungle, with some suffering from malaria.

She recalls Leroy’s photographing the assault on Hill 881, where the Marines had 900 casualties and one captured image of a medic, Vernon Wike, cradling a dead Marine. Ms. Becker also offers a graphic visual of the post-battle terrain. “The bombing has defoliated the jungle and plowed up the earth, leaving an empty landscape of dead wood blackened by explosions and muddied by monsoon rains.”

The book’s narrative shifts intermittently to Frances Fitzgerald, author of the Pulitzer and National Book Award for “Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam. The Radcliffe graduate and daughter of deputy CIA Director Desmond Fitzgerald and a socialite mother, Marietta Peabody, arrived initially in Vietnam as a freelance journalist.

From Ms. Fitzgerald’s coverage in the Mekong Delta, to her examination of the hospital wards, to the glitzy Black & White Ball hosted by Truman Capote in 1966, and the love affair between Ms. Fitzgerald and Ward Just, Ms. Becker offers just enough backstage gossip to propel the narrative forward from the fog of war.

Ms. Becker’s assessment of Ms. Fitzgerald’s contribution to the war reporting effort is evidenced in this assessment. “She (Fitzgerald) described how the Americans had little interest in understanding the Vietnamese as a separate culture outside the American experience …”

Her reportage invokes at times her own reveries when describing her close friend, Kate Webb, who in 1967 became the first United Press International (UPI) woman resident correspondent in Vietnam. Ms. Webb distinguished herself for fearless battlefield reporting and at one point was held prisoner for weeks by North Vietnamese troops. New Zealand-born and Sydney-trained, she spent more than six years covering the war, including crossing into Cambodia.

Like her subjects, Elizabeth Becker felt the same “compulsive pull” that had propelled Ms. Webb and others to bear witness to war. By April 1973, Phnom Penh became the new front line.

“Nothing in my short life had ever mattered as much as witnessing Cambodia’s war as a reporter. Every part of everyday had meaning. I had never felt more involved, more alive, or more vulnerable,” writes Ms. Becker.

Women reporters went to Southeast Asia because it was the most important story of the decade and they wanted to be part of it. Most of them fought and won battles on and off the field, too. However, what’s clear is their perspectives and wide-angle lenses allowed Americans a glimpse into the war’s effect on soldiers and locals.

• James Borton is a veteran journalist who has reported on Southeast Asia for more than two decades and who frequently writes for The Washington Times.

• • •

YOU DON’T BELONG HERE: HOW THREE WOMEN REWROTE THE STORY OF WAR

By Elizabeth Becker

PublicAffairs, $28, 320 pages

Please read our comment policy before commenting.