The Defense Department on Monday issued long-awaited rules to identify and root out political extremism in the armed forces, specifically zeroing in on social media and giving new guidance to commanders who will be responsible for policing their units.

Acknowledging the need to thread “a very fine needle” with respecting First Amendment rights, senior defense officials said that the new policy — which has been under development for nearly a year — is “group agnostic,” meaning that simple membership in a white supremacist organization or other extremist outfit won’t technically violate military guidelines.

But active participation in such groups isn’t allowed, nor is any attempt to share extremist content online, recruit other potential members, or otherwise promote a hateful, anti-government or discriminatory ideology.

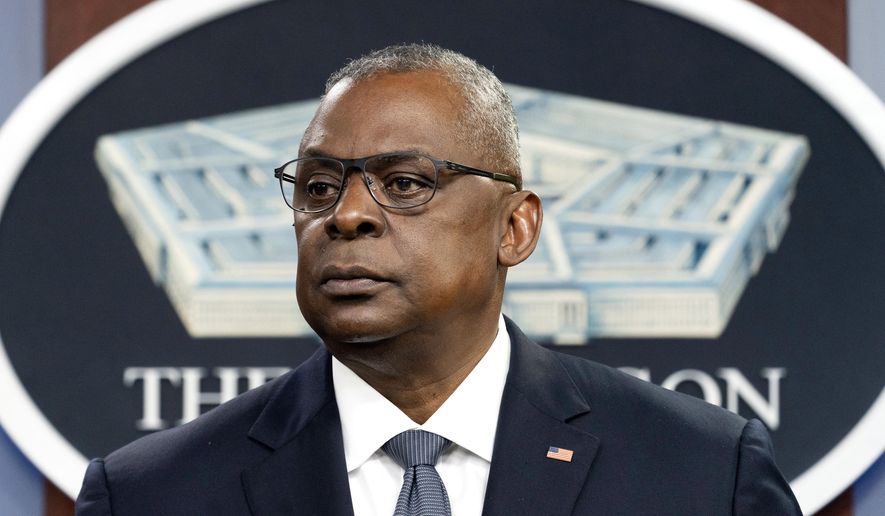

Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, who launched the counter-extremism push in the weeks immediately after the Jan. 6 Capitol riot, said the new guidelines will strengthen the military.

“The overwhelming majority of the men and women of the Department of Defense serve this country with honor and integrity. They respect the oath they took to support and defend the Constitution of the United States,” he said in a memo to Pentagon leaders Monday. “We believe only a very few violate this oath by participating in extremist activities, but even the actions of a few can have an outsized impact on unit cohesion, morale and readiness — and the physical harm some of these activities can engender can undermine the safety of our people.”

The new policy is sure to be controversial. Critics have argued that the Pentagon’s anti-extremism push has often appeared overly broad and could be viewed as inadvertently — or perhaps intentionally — targeting conservatives or Christians, for example. Some Republicans on Capitol Hill have argued a “woke” military under President Biden is more interested in policing the opinions of those in the ranks than it is in training soldiers and sailors to fight wars.

The issue attracted more urgency after it was revealed that scores of participants in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot had a military background, including at least one active-duty Marine. The military’s anti-extremism push was one of Mr. Austin’s first initiatives after taking office in February.

The new Pentagon rules do not offer a specific list of extremist organizations. Instead, they identify broad classes of extremist activities and then provide more than a dozen definitions of “active participation” to military commanders.

The commanders then will use those definitions, along with other factors, to determine whether service members in their unit violated the policy and should be subject to discipline.

The definitions of “extremist activity” include: advocating or engaging in unlawful force or violence to deprive others of their constitutional rights; advocating or engaging in unlawful force or violence to achieve a political or ideological goal; advocating or supporting terrorism; advocating or supporting the overthrow of the government; encouraging military or civilian personnel to violate U.S. laws; and advocating discrimination based on, race, color, religion and other factors.

The definitions of active participation, meanwhile, focus more on specific actions an individual might take toward those broader aims, such as demonstrating, rallying, attending meetings, sharing information, recruiting others, sharing literature or displaying words or symbols known to be associated with extremist groups.

The Pentagon has vehemently denied that politics plays any role in the initiative, and officials said they went to great lengths to protect free speech rights to the extent possible.

“It’s threading a very fine needle when we’re engaging in prohibiting conduct that may be protected by the First Amendment,” a senior defense official told reporters on a conference call Monday afternoon. “We have more flexibility than we do with the civilian population, nevertheless we’re aware of trying to protect service members’ rights. … There’s always going to be this balancing going on.”

Promoting terrorism or actively working to overthrow the government are among the banned activities laid out in the new Pentagon policy, which comes amid fears that extremism is spreading in the ranks as American political and cultural divisions seemingly grow deeper.

In all of 2021, officials said they identified about 100 cases of extremism among active-duty military personnel, up from the “low double digits” across each of the services in prior years.

Moving forward, officials believe the new policy will make it easier to identify cases of extremism while also clarifying the rules of the road, both for commanders and the men and women in their units.

For example, simple membership in a group isn’t outlawed, but officials said the rules are strict enough that it will be impossible “for someone to be a member of an extremist organization in any meaningful way.”

The most notable changes come in the realm of social media.

While previous extremism policies lacked specifics as to what is and isn’t allowed on Twitter, Facebook or other avenues, the new guidance zeroes in on social media engagement designed to promote the message.

In other words, simply viewing an extremist page isn’t necessarily a violation of the policy. But any engagement with that page — including “liking” its posts — likely would be.

“There has to be amplification of the message,” a defense official told reporters.

Still, the Pentagon acknowledged that individual cases will vary and that commanders will carry much of the burden in determining whether a service member should face discipline.

“It will be very, very fact-specific, something the commander is going to have to look at, along with their legal counselor, to assess,” the defense official told reporters.

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.