Social Security’s revenue will begin to decline this year, crossing a critical fiscal threshold as the program begins a slide toward depletion of its trust funds in little more than a decade, the program’s trustees said in a stark report Tuesday.

And both of Social Security’s benefit programs, Old-Age Survivors Insurance for older adults, and Disability Insurance for those unable to work, failed the trustees’ tests of short-range financial adequacy.

The revenue decline had been predicted in previous reports, but its arrival is still a stark warning sign in the federal government’s fiscal health checkup.

The trustees said that while the trajectory has been grim for some time, the coronavirus pandemic and the economic downturn it spawned took a significant toll on Social Security, slicing a year off the deadline for when the trust funds will be depleted and the program will no longer be able to pay out full promised benefits.

The new deadline is 2034, and payments will be reduced to 78% of what was promised, the trustees said.

“The pandemic and precipitous recession have clearly had significant effects on the actuarial status of the OASI and DI Trust Funds, and the future course of the pandemic is still uncertain,” the trustees said.

Medicare was also slammed by the pandemic, said the trustees, as income plummeted and expenses surged, with payments for testing and treatment of an older population particularly ravaged by the disease.

But Medicare beneficiaries also put off procedures amid the pandemic, “more than offsetting” the new costs, the trustees said in a separate report on Medicare, the federal health program for those 65 and older.

The trustees didn’t calculate the impact of higher death rates on Medicare but said otherwise, the pandemic is expected not to change the program’s outlook, where it faces “a substantial financial shortfall.”

The 2021 reports are the first to take full stock of the pandemic.

For Social Security, the trustees said COVID-19 deaths have cut into the projected growth of old-age beneficiaries. It also said people were chased out of the workforce, sapping the program of income. And a birth dearth has cut into the future workers the program had projected in previous reports.

Last year’s report came early in the pandemic and didn’t include much of the economic chaos the virus has caused.

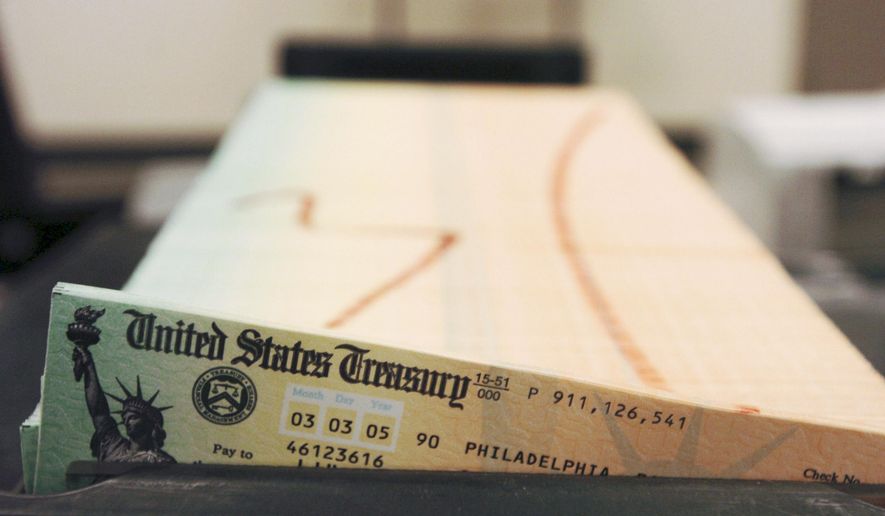

Social Security is funded by a payroll tax applied to wages earned. It is not a welfare program but is instead supposed to be a type of pension, in which Americans across the income spectrum pay into it and get benefits commensurate with those payments.

The program’s finances have been declining for years, with annual payroll tax income insufficient to cover the program’s benefit payments since 2010.

But the program has been coasting on interest paid into the trust funds over the previous 25 years, when revenue was greater than payouts and the excess income was pumped into the trust funds, earning interest from intragovernmental loans.

This year will be the first that the combined income from payroll taxes and interest won’t be enough to cover promised benefits, the trustees said. That imbalance will continue for the rest of the century, with the two combined trust funds depleted in 2034.

Under the law, Social Security then will have to cut its payments to meet income, and will pay out 78 cents on each dollar the program has promised to pay. By 2095, the end of the 75-year actuarial period the trustees studied, the program will pay out 74 cents of each dollar promised.

“If we wanted to fix the system and we wanted to act immediately, we would have to cut benefits 21% next year,” said Chuck Blahous, who used to serve as one of the public trustees for Social Security.

Underlying the imbalance is the ratio of workers supporting retirees.

From 1974 to 2008, the ratio was 3.2 to 3.4 workers per beneficiary. That began to decline with the Great Recession, and is now down to 2.7 workers per beneficiary. By 2035, when baby boomers will mostly have retired, it will be 2.3 workers per beneficiary.

Efforts to overhaul Social Security have gone nowhere on Capitol Hill over the years, with Democrats’ demands for bigger benefit checks sunk by the fiscal realities of paying for them.

On Tuesday, a key Democrat said it’s time to try again.

“It has been 50 years since Congress has done anything to improve benefits,” said Rep. John B. Larson, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee’s Social Security subcommittee. “The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored just how important this program is to our country, never missing a payment even during economic downturns. We must work to expand benefits now and strengthen the program for today’s seniors and generations to come.”

Even before talk of expanding benefits, though, budget watchdogs said it’s time Congress fixes the existing imbalance.

“It makes no sense that we allow programs as essential as Social Security and Medicare to remain on such shaky and uncertain fiscal ground,” said Michael A. Peterson, CEO of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation.

He said the solutions are known, “and it is fully within our lawmakers’ control to put these programs on a more sustainable path.”

Mr. Blahous said the numbers are so bad that both sides of the ideological spectrum must give — conservatives will have to embrace tax increases, and liberals will have to stomach benefit cuts — to fix it.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.