OPINION:

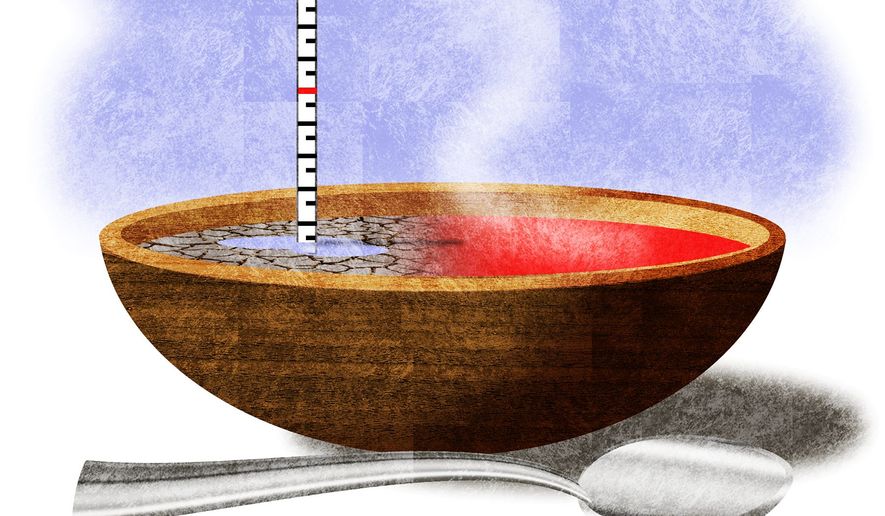

The American West is witnessing a climate disaster. The 21-year drought is the second-worst since the year 800.

Regional authorities planned reasonably well but what’s happening in the West is not a millennial event. Thanks to global warming, a more arid climate, and scorching temperatures are now a permanent condition. Solutions require federal involvement, not merely to see farmers and municipalities through the next few years, but to harden infrastructure and promote patterns of conservation in the national interest.

Rivers won’t be low and thermometers won’t reach new highs each year, because dry conditions and heat won’t be annually exacerbated by shifts in the jet stream and ocean currents. Those created the heat domes in the West and massive flooding in China, Germany, Belgium, and elsewhere.

Larger and more intense forest fires, water shortages, and lost hydroelectric capacity will occur with greater frequency. The West is making tough choices that make sense to the region but perhaps not for the whole country.

Western states have supported booming cities and agriculture for more than a century with complex systems of damns, reservoirs, canals, and by tapping groundwater.

Most compelling is the Hoover Dam. Completed in 1935 at a junction between Arizona and Nevada, it tamed the mighty Colorado River and created the nation’s largest artificial store of water at Lakes Meade and Powell. Those are currently at about one-third capacity.

Slipping fast are California’s reservoirs—Shasta, Orville, San Luis, and others, and those patterns repeat throughout the West.

Many reservoirs are replenished each spring by mountain snow melts. With higher winter temperatures, less snow accumulates, and the dry ground, trees, and other plants absorb more water before it gets to streams or sinks deeper into aquafers. Higher temperatures cause more evaporation in river systems and lakes.

The upper Midwest faces more frequent droughts too. The Ogallala Aquifer, which supports farming from Texas to South Dakota, is depleting.

Over the last century, water allocations have permitted farmers and ranchers to prosper, and the nation and the world have become increasingly dependent on western fruits and vegetables, cattle, and other commodities—that cannot be easily reversed.

The Northeast was much more food self-sufficient 150 years ago, but the opening of the Midwest for crops like wheat and corn and transcontinental rail transportation and refrigeration created new dependencies. Farmland in the East became suburban subdivisions and forests again. In many places, that cannot be easily reversed.

This interstate trade is based on comparative advantage—California and Arizona have more winter sunshine and fewer field stones than New England—and regional specialization that has taken global proportions. California grows 80 percent of the world’s almonds, but now the lack of water is forcing farmers to abandon orchards.

The Northeast could grow its own string beans but it lacks the climate and land to replace California’s winter lettuce.

In Arizona, Nevada, and elsewhere in the West, water has been more effectively conserved by municipalities through higher water rates and novel technologies but with populations rapidly growing, these have limits.

San Diego draws 10 percent of its water from the Carlsberg Desalinization Plant. But that is hardly a generalizable solution because the process is terribly energy-intensive and the bioproduct of salt and other minerals potentially causes significant environmental damage if dumped back into the ocean.

The more frequent solution has been to shift water allocations from farms to households and businesses, and this supports the region’s tourism, high-tech activities, and manufacturing renaissance. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and Intel are planning chip factories for Arizona.

While those industries may be higher value-added propositions and create desirable jobs for western states, the impact on the national food supply and economy could be wrenching. The overall economic cost to the nation imposed by high grocery prices and importing more food could easily outweigh the regional benefits.

A coalition representing western farmers, ranchers, water providers, businesses, and municipalities has identified a 10-year $49 billion program to invest in conservation and recycling, conveyance, desalinization, groundwater storage, and surface storage, and the need is likely a lot larger.

The bipartisan infrastructure plan wending its way through Congress contains $105 billion for water resiliency and drinking water programs—for example, to eliminate lead in the nation’s service lines and pipes—but only $8.3 billion for western water projects.

President Trump established a Water Subcabinet to coordinate interagency efforts to assist state water managers to invest in conservation and new technologies, but more comprehensive federal-state planning is needed to effectively target federal cost-sharing and place agriculture on an equal footing with urban growth.

• Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland, and a national columnist.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.