OPINION:

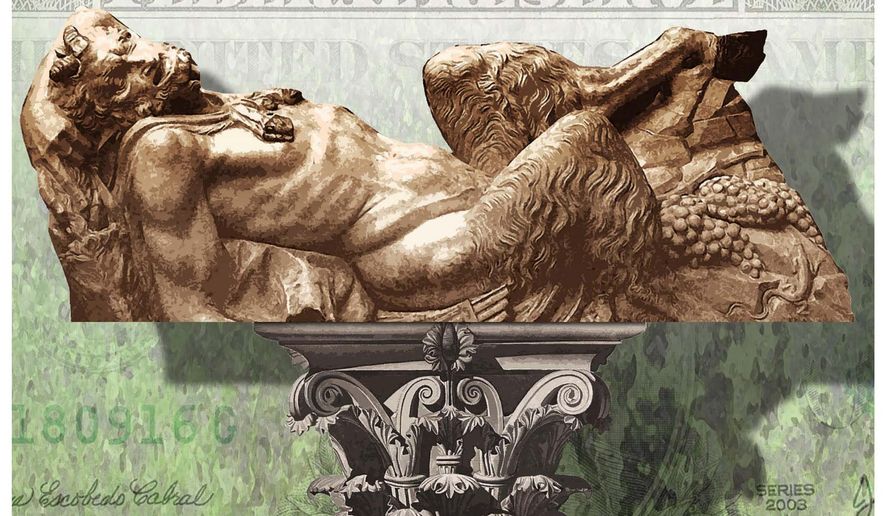

The Federal Reserve has become a decadent institution. If it does not scale back easy-money policies soon, Americans risk a deep recession or at least stagflation.

Last August, the Fed announced that it would prioritize “maximum employment” and no longer act preemptively to stem inflation. It would accept a period of inflation greater than 2% to compensate for undershooting that target in the 2010s.

Since April, the annualized pace of month-over-month inflation has been 8.7%. That cannot be attributed merely to adjustments in pandemic depressed prices for airplane tickets, rental and used cars, hotel rooms, and the like. Consumers are complaining about higher prices for houses, cars, household appliances, and other goods, postponing discretionary purchases, and expect inflation to be near 5% for the next year.

The change in the Fed’s policy framework is anchored in the view that it tightened too quickly in the past and denied workers the opportunity to enjoy a sellers’ labor market and bargain for higher pay.

That’s a “progressive” urban legend.

In this century, the Fed has raised interest rates in steps twice—June 2004 to June 2006 and December 2015 to December 2018. During both episodes, the unemployment rate continued to fall.

By June 2019, unemployment reached 3.6%, but Mr. Powell let President Trump bully him into stopping the process, and now Biden White House economists have a preference for accommodative policies.

The Fed has lost its political independence.

In 2013, Chairman Bernanke raised the idea of scaling back the Fed’s holdings of mortgage-backed securities. The 10-year Treasury rate jumped, a stock market rout was feared, and Mr. Bernanke proceeded to add more than another $1 trillion to the Fed balance sheet, not the reverse.

Monetary policy is supposed to work by the Fed influencing interest rates through the bond market. Still, as the “temper tantrum” illustrated, financial markets dictate what the Fed can do. It’s all silly because historically, we have had much higher interest rates and thriving equity and housing markets.

The current economic recovery has reached the point that the Fed should be scaling back its Treasury and mortgage-backed securities purchases. Employers have millions of jobs they can’t fill. Issues include fear of COVID-19 among many who refuse vaccinations, federal supplemental unemployment benefits, inadequate childcare, and a mismatch between the skills and location of jobs seekers and vacant positions in the post-pandemic labor market.

Easy money and instigating more inflation won’t change those conditions, but easy money enables large federal deficits. If the Biden administration had to pay 3.5% instead of 1.5% on the federal debt, it would be more careful about what it spends.

Fed bond purchases artificially suppress mortgage rates, but that does nothing to increase the supplies of scarce building lots, materials, and skilled tradespeople.

Pulling back on those purchases would raise mortgage rates and limit bidding wars for new homes but have little impact on new home construction and employment.

As lumber prices have receded owing to an unwinding of hoarding. Builders are not reducing prices because, like university masters programs with overpriced tuition, they know home buyers have cheap credit enabled by the Fed to sustain inflated prices and bloated profits.

Waiting too long to tighten monetary policy, the Fed is distorting capital markets—in particular, corporate junk bonds are being sold at terribly low rates. Bankruptcies that should have occurred have become zombie enterprises. Similarly, some of the spectacular valuations of IPOs would not be possible if the Fed were not pumping so much liquidity into capital markets.

Importantly, raising short-term interest rates and slowing bond purchase can take considerable time to affect business decisions and rein inflation.

With is permissive policies, when inflation forces the Fed to tighten, the cycles of rising wages and prices will be entrenched and difficult to break. Higher interest rates will unleash a greater wave of corporate bankruptcies and layoffs, and the pull-back in home prices will put recent buyers underwater on their mortgages.

Mr. Powell will face a choice between a tough, deep recession and stagflation—somewhat elevated unemployment and inflation at 3% to 5% and perhaps higher.

The longer Mr. Powell waits, the worse it will be for him, congressional Democrats, and President Biden.

This fall, as schools reopen and federal unemployment benefits end in blue states, Mr. Powell should begin raising the federal funds rate and scaling back Treasury and mortgage-backed security purchases.

That might cost him his job, but I won’t want his legacy if he caves to the preferences of the Biden administration.

• Peter Morici is an economist and emeritus business professor at the University of Maryland and a national columnist.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.