Several cities and states, including some jurisdictions with White majorities, are backing the explosive idea of giving Blacks reparations in recognition of slavery and racism in the nation’s past.

But supporters of the idea have not reached a consensus about how reparations would work.

The politically charged idea of sending checks to all Black people remains on the table. But most plans, such as a measure approved by the St. Paul, Minnesota, City Council in February and a bill in the U.S. House, do not go that far.

In many cases, the proposals would create commissions to examine questions such as defining what form reparations might take.

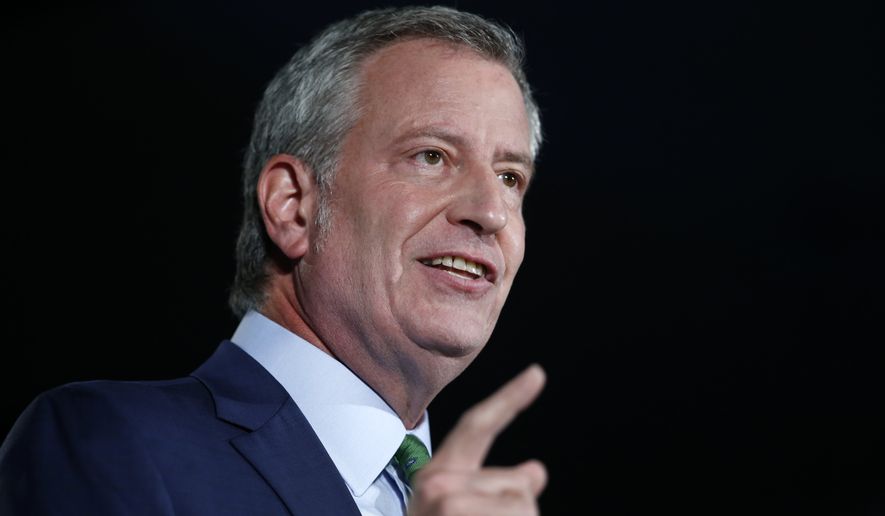

Two weeks ago, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, a Democrat, created a Racial Justice Commission to examine the question. He did not spell out what reparations would mean, but among the possibilities are making payments to Blacks or creating savings accounts for Black infants.

Other reparations proposals, including one approved by the City Council of Evanston, Illinois, two weeks ago, focus on providing redress for specific wrongs, such as city policies that prevented Blacks from buying homes or were aimed at keeping them in poor neighborhoods.

The city will give $25,000 to Blacks who lived in Evanston from 1919 through 1969, when the discriminatory housing policies were in place, or are descendants of Blacks who lived in Evanston during that time. The reparations must be used for housing-related costs such as down payments or home repairs.

Evanston’s population is 66.6% White and 16.5% Black, according to the latest census data.

Many believe the use of reparations to address past racism is itself racist.

The goal of a “‘color-blind’ society is now directly under attack by this unjust Evanston measure,” Rep. Tom McClintock, California Republican, said at a House Judiciary Committee hearing in February on a Democratic bill to create a reparations commission.

The proposal “requires people who never owned slaves to pay reparations to those who never were slaves, based not on anything they had done but because of what race they were born,” he said.

But to Robin Rue Simmons, the Evanston alderwoman who proposed the measure, past discriminatory housing policies meant that Whites, unlike Blacks, had homes that grew in value and were able to pass on that wealth to their children.

The policies might be long gone, but their impact is still being felt in the wealth gap between Blacks and Whites today, she said. Reparations proponents say the gap has to be addressed.

But Mike Gonzalez, a senior fellow at the conservative Heritage Foundation, said proposals aimed at helping only some Blacks, such as farmers eligible for loans for people of color in last month’s coronavirus relief bill, are unfair. He said the measure is based on the color of people’s skin, not on whether they need the money, and he asked whether wealthy Blacks such as Oprah Winfrey should get reparations.

“America has been free of government-mandated racial discrimination now for nearly 60 years. It should remain that way and not reintroduce this vile idea in order to address disparities,” said Mr. Gonzalez, author of “The Plot to Change America: How Identity Politics Is Dividing the Land of the Free.”

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, Kentucky Republican, said last year that he didn’t think “reparations for something that happened 150 years ago” was a good idea.

“We’ve tried to deal with our original sin of slavery by fighting a civil war, by passing landmark civil rights legislation. We elected an African-American president,” Mr. McConnell said.

Studies show that a wide gap persists in the wealth of Blacks and Whites and has grown since the Civil Rights movement.

In 1968, the average middle-class Black household had $6,674 in wealth, one-tenth of the $70,786 for the typical middle-class White household, according to the Federal Reserve Board. By 2016, the typical middle-class Black household had $13,024 in wealth, one-twelfth of the $149,703 of the median White middle-class household.

That disparity is passed down. In 2019, a study by the left-leaning Brookings Institution said 30% of White households received an inheritance and the average was $195,500. Only 10% of Black households received an inheritance, $100,000 on average.

What to do about the gap isn’t clear, even among proponents of reparations.

Evanston’s decision to initially limit how the money can be used was opposed by some. They said the government has no right to dictate what Blacks can do with the redress.

The money amounts to 4% of the $10 million that Evanston has committed for reparations over the next decade. A commission created by the city could opt to send checks to all Blacks or focus on other areas such as education or entrepreneurship.

Cornell Brooks, a professor at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and former president of the NAACP, said reparations should give money directly to all Blacks.

“The point is to erase the racial wealth gap,” he said.

Pennsylvania state Rep. Chris Rabb has a different approach. The Democrat, who represents a largely Black section of Philadelphia, said he plans to introduce a bill this year to create a state reparations commission.

He hasn’t ruled out the idea of making payments to all Blacks. But instead of a one-time payment, he would create a pot of continuous funding for areas such as education until racial equity increases.

“We need a systemic solution because we’re dealing with a systemic problem,” Mr. Rabb said.

New York state Sen. James Sanders Jr., a Democrat, is also sponsoring a bill to create a reparations commission. Mr. Sanders said reparations for younger people should go for education or buying homes, which could help close the wealth gap over time.

Congress included $5 billion in farm loans for people of color in last month’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package. Black farmers in the past were denied federal loans that White farmers were able to obtain. Advocates say the loans could help preserve Black-owned farms.

A proposal by Sen. Cory A. Booker, New Jersey Democrat, calls on the federal government to buy 32 million acres of farmland and sell it only to people of color under favorable terms.

Mr. Brooks said it’s telling that even a proposal to form a commission, such as a House bill proposed by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, Texas Democrat, is controversial because Congress routinely creates such panels. It points to “the fear there is in talking the truth about our country,” he said.

At the hearing on Ms. Lee’s bill, former NFL star Herschel Walker said the idea would split the nation further apart on race.

“My religion teaches togetherness,” he said. “Reparation teaches separation.”

• Kery Murakami can be reached at kmurakami@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.