A Supreme Court ruling that bars state prosecutions of American Indians in Oklahoma for crimes on tribal land has led to a wave of appeals from convicts, a rising backlog of cases in federal and tribal courts, and an accused serial rapist walking away free on a technicality.

“If you were going to make a nightmare, you couldn’t make one better than this,” said Scott Walton, sheriff in Rogers County, Oklahoma.

Before the high court handed down its ruling in July, the U.S. attorney’s office for the Northern District of Oklahoma prosecuted about 240 cases a year. The office now is indicting about 100 cases a month, about five times more, as the federal government picks up cases formerly in the state’s jurisdiction.

In the past eight months, the U.S. attorney’s office has accepted 600 major felony cases for prosecution and sent 830 less-serious cases to tribal courts.

Some prosecutions are falling through the cracks because of statutes of limitation for some federal crimes — a legal hurdle state prosecutors didn’t face.

“There is a small percentage of cases that cannot be prosecuted due to lack of/loss of evidence or due to the federal statute of limitations,” said a spokesperson for the U.S. attorney’s office in the Northern District of Oklahoma. “Our office continues to work closely with district attorneys and tribal attorneys general to ensure a seamless transfer of cases for prosecution.”

For minor crimes that carry maximum prison sentences of three years or less, tribal courts have the authority to prosecute defendants. Critics say the Supreme Court’s 5-4 ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma left certain crimes such as larceny, which can carry a five-year sentence, in limbo between tribal courts and federal courts.

Another concern is that federal prosecutors will focus on violent crimes such as rape and murder, leaving home burglary and others unresolved.

“Those cases just won’t get prosecuted,” Sheriff Walton said.

The McGirt case has major implications in Oklahoma because about half of the land in the state is considered Indian country, covering dozens of tribes. The city of Tulsa, which has a population of more than 400,000, sits predominantly on a reservation.

The high court’s ruling, which sent shock waves through the state, overturned the conviction of Jimcy McGirt, an American Indian charged with sexually abusing a 4-year-old girl in 1996.

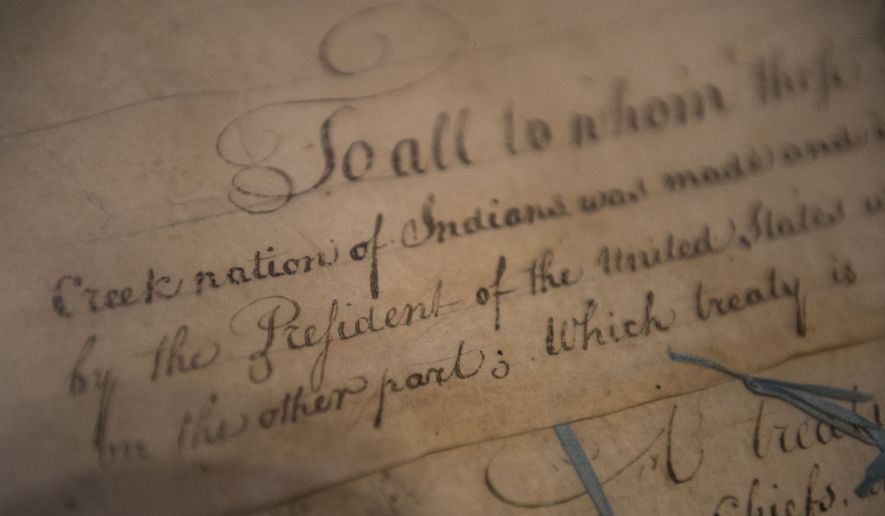

The court’s majority agreed with McGirt’s argument that the state didn’t have jurisdiction to prosecute him because the crime took place on a reservation and he is American Indian. The justices said Congress never disestablished the 1860s-era boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, a Trump appointee, joined four Democratic appointees, including Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in overturning McGirt’s conviction.

The federal government retried McGirt four months later. McGirt was found guilty in November of two counts of aggravated sexual abuse and one count of abusive sexual contact. Each count carries a sentence of at least 30 years in prison.

“Prosecuting decades-old cases are difficult at best, but the prosecution team, along with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, demonstrated tenacity and commitment to the federal government’s trust responsibility in Indian country in the Eastern District of Oklahoma,” U.S. Attorney Brian J. Kuester said at the time.

Some other prosecutions haven’t been able to move forward. In one high-profile case, a federal judge in August dismissed charges against Leroy Smith, who was accused of raping five women in Muskogee County in the 1990s.

The judge ruled that the federal statute of limitations had expired in a case that was moved out of state court after the Supreme Court’s decision. Smith maintained his innocence. State prosecutors charged him after getting a DNA match in their “cold case” investigation.

The federal statute of limitations is a major concern of state law enforcement officials. Once a conviction is overturned, they say, there is no guarantee that federal prosecutors or tribal courts will be able to prosecute the accused person again.

Even if another trial is held, they say, witnesses’ memories may have faded and some could have died since the original proceedings.

“These are all concerns we have been struggling with,” said Oklahoma Attorney General Mike Hunter. “The statute of limitations issue is something that we struggle with here. We do our best to communicate and stay in close contact with the federal government — with particularly the more serious crimes — to make sure someone doesn’t use ‘McGirt’ as a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

Mr. Hunter said the state does not have a statute of limitations for rape, but federal courts place time limits on filing charges for certain rape crimes.

State law enforcement officials say federal courts already were handling many cases before the ruling ordered them to pick up crimes from state courts.

The U.S. attorney’s office for the Eastern District of Oklahoma, like the Northern District, has had a surge in cases. In one week this month, the office returned 90 felony indictments — more than the office normally brings in a full calendar year.

An internal source said the U.S. attorney’s office for the Eastern District could be handed 200 murder cases to try by the end of May.

“It is a conundrum without certainty,” the source told The Washington Times, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “We need some sort of legislative fix.”

Many convicted felons are citing the McGirt case in appeals in an effort to overturn their sentences.

Robert Gifford, a lawyer who works with tribes in Oklahoma, dismissed law enforcement’s concerns. He said most accused felons will be prosecuted again.

“They are portraying it that these people are walking free, but most of the major cases are being picked up federally,” he said. “Any major crimes would go to the U.S. attorney’s office.”

A spokesperson from the Justice Department did not return a request for comment about the implications of the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Mr. Hunter said he would like the state to have concurrent jurisdiction with the tribes, but Congress would need to enact a law authorizing the state and the tribes to negotiate joint jurisdiction.

Oklahoma lawmakers have not introduced such a bill, but any federal law would require the tribes to reach a deal with the state to resolve another hurdle.

“It’s definitely a process, and it’s complicated by the fact that only two of the five tribes are supporting that legislation,” Mr. Hunter said.

Sara Hill, attorney general for the Cherokee Nation, said her tribe would like the power to negotiate with the state because the federal system has put it in a complicated situation.

“We would definitely like to have the option to do that,” she said. “It would be good especially in those cases where the tribe cannot exert jurisdiction over non-Indians. It’s a complex issue, and I think the primary thing that the nation wants is … to be able to make decisions on our reservation. That makes sense for us. We want the authority to be able to do that.”

Ms. Hill said the Cherokee Nation has spent $10 million to prepare the tribal courts for the increased docket.

More than 530 criminal cases have been filed in the Cherokee Nation, more than the tribe had in the previous 10 years.

• Alex Swoyer can be reached at aswoyer@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.