OPINION:

“The Constitution is not neutral. It was designed to take the government off the backs of the people.”

— Justice William O. Douglas (1898-1980)

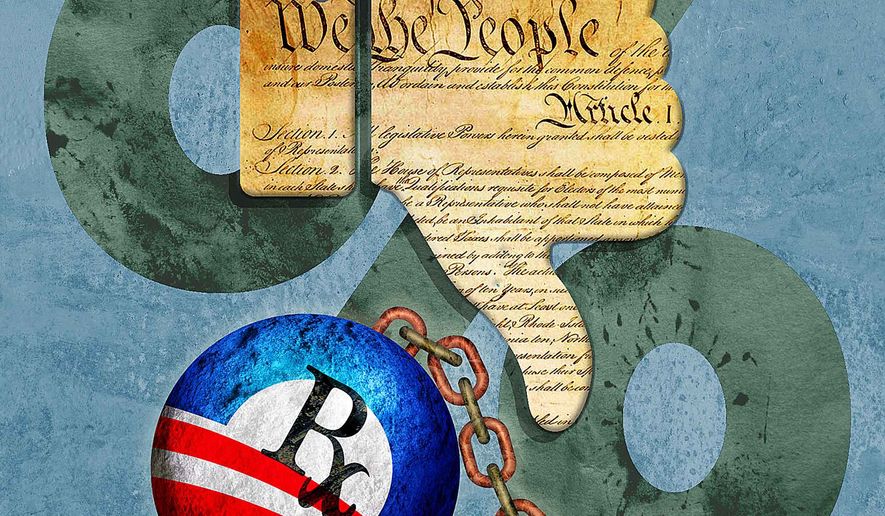

With President Trump’s nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the U.S. Supreme Court, the Affordable Care Act — Obamacare — is back in the news. Judge Barrett expressed constitutional misgivings about Obamacare 10 years ago when she was a professor at Notre Dame Law School, and some folks who oppose her nomination have argued that should she be confirmed in the next month, she should not hear the Nov. 10 arguments on Obamacare.

Wait a minute. Didn’t the Supreme Court already uphold Obamacare in 2012? Yes, it did. So why is the constitutionality of this legislation back before the Supreme Court?

Here is the backstory.

The Affordable Care Act of 2010 marked the complete federal takeover of regulating health care delivery in America. It eliminated personal choices and mandated rules and regulations on almost all aspects of health care and health care insurance. It created a complex structure that, at the back end, directed the expenditure of hundreds of billions of dollars on health care and, at the front end, received health insurance premiums from or on behalf of every adult in America.

To assure that every adult obtained and paid for health care coverage, the ACA authorized the IRS to assess those who failed to have health insurance about $8,800 a year and use that money to purchase a bare-bones insurance policy for them.

The requirement of all adults to maintain health care coverage, and the power of the IRS to assess them if they don’t, is known as the individual mandate.

When the ACA was challenged in 2012, the challengers argued that Congress lacked the constitutional power to micromanage health care and to enforce the individual mandate. The feds argued that this was all “interstate commerce” and Congress’ reach in this area is broad and deep.

Yet, both the challengers and the government agreed that the IRS assessment was not a tax. The challengers argued that it was a penalty for failure to comply with a government regulation, and thus those not complying with the individual mandate were entitled to a hearing before they could be punished.

The government argued that the assessment was triggered by people choosing freely to have the feds purchase their insurance for them. The feds could not argue that this assessment was a tax because President Obama had promised that his health care programs would not increase anyone’s taxes.

In 2012, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the individual mandate was a tax and since, under big government constitutional jurisprudence, Congress can tax anything it wants, the ACA was constitutional.

This logic was deeply disconcerting to those of us who believe that the U.S. Constitution doesn’t unleash the federal government but restrains it. The Constitution was written to keep the government off our backs. Yet, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote, along with his four liberal colleagues, that while Congress cannot order us to eat broccoli, it could tax us if we don’t. The same, he reasoned, is the case for maintaining health care insurance.

In 2017, Donald Trump became president and the Republicans retained control of Congress. During a massive reform of American tax law, Congress did away with the tax on those who fail to maintain health insurance by reducing it to zero. Then, 18 states challenged the ACA again, this time arguing that since there was no longer a tax associated with the ACA, and since the tax formerly associated with it was the only hook on which the Supreme Court hung its constitutional hat, the ACA was now unconstitutional.

A federal district court and the 5th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals agreed, and the lawyers representing the federal government filed an appeal to the Supreme Court. I wrote “the lawyers representing the federal government” because the Department of Justice, which defended the statute in the district court, withdrew from the case under Mr. Trump’s orders.

Then, the House of Representatives hired a team of private lawyers to defend the statute. This is very irregular. The presidential oath requires that the president “faithfully execute” his office. James Madison — who wrote the oath and many other parts of the Constitution — insisted on using the word “faithfully” because he anticipated the presidential temptation to enforce only statutes with which a president agrees. The word faithfully was intended to remind presidents of their oath of fidelity to the Constitution and all laws written pursuant to it, whether they agree with those laws or not.

Now, back to Judge Barrett.

When she questioned the chief justice’s logic about congressional taxation used to bootstrap a 2,700-page regulatory takeover of the delivery of health care, she did so in an academic setting designed to stimulate student understanding; she did not do so as a judge. Having taught law school for 16 years, I can tell you that professors of law often make provocative remarks just to see how students will analyze them. Their remarks are hardly a textual commitment to a legal position.

Yet, Judge Barrett’s remarks were well-grounded, and Justice Roberts’ broccoli example is telling. What is the effective difference between ordering me to eat broccoli and taxing me if I don’t? Nothing except a rejection of the Constitution as an instrument designed to preserve freedom — a design that rarely works that way today.

Its original end was that the government leaves us alone. But that end is no longer in sight.

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.