When it comes to what to do about China, the 2020 presidential contest may be more about style than substance.

Analysts and foreign policy insiders say a rapid shift in American politics has pushed President Trump and Democratic presidential nominee Joseph R. Biden onto shared turf. The two men still have notable policy differences, but Beijing’s economic rise, growing military adventurism and long-term plan to knock the U.S. off its perch as the leader of the 21st-century global order have fueled a growing bipartisan consensus on big-picture points and spawned fiery rhetoric on both sides of the aisle.

The result is a much more skeptical view of Beijing among leading Republicans and Democrats — and the necessity for virtually all candidates to appear “tough on China.” That new reality has left Mr. Biden — a foreign policy establishment mainstay in Washington with decades of experience on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee — in a far different place than he was during his eight years as vice president during the Obama administration.

“There’s clearly bipartisan consensus in Washington on hardening U.S. policy toward China. I think there’s almost an inevitability that Biden also would seek to take a very tough line on China, fundamentally different than where the Obama administration was several years ago,” said Mark Simakovsky, former chief of staff for Europe and NATO in the office of the secretary of defense for policy and now a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council.

“I think there is natural progression in U.S. policy,” he told The Washington Times in an interview.

Mr. Trump and his administration’s China hawks may have pushed the envelope, starting a tariff war with Beijing, repeatedly denouncing the “Chinese flu,” and taking precedent-breaking steps in support of Taiwan, but neither party sees any political gain in going back to a more conciliatory and cooperative relationship with China’s Communist Party leadership.

Indeed, the core of Mr. Trump’s and Mr. Biden’s approach to the People’s Republican of China (PRC) is similar in many key ways, though the former Delaware senator has stressed that he would rely less on bilateral confrontation and more on regional and global partners to exert leverage on China, while continuing to use the U.S. military to keep Chinese expansion in check. Mr. Biden also has argued that he would shine an even greater spotlight on China’s human rights violations, such as its treatment of its Uighur Muslim minority and its recent security crackdown in Hong Kong.

Mr. Trump, meanwhile, has made China a central foil throughout his political career, arguing that past administrations of both parties have allowed Beijing repeatedly to “rip off” America and undermine its manufacturing base. That belief has driven the president to take dramatic action on trade and diplomacy, including the recent closure of China’s Houston consulate that U.S. officials charged was at the center of a spy ring.

Senior Trump administration officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and FBI Director Christopher A. Wray gave a series of harsh addresses this summer outlining the diplomatic, economic and security dangers posed by China. Some Trump backers have even spoken of “decoupling” the U.S. and Chinese economies, setting up separate spheres of commercial interest and online activity for the globe’s two biggest economies.

Not unexpectedly, the candidates are responding to the voters.

A Pew Research Center survey in late July found anti-Chinese feeling at a record high among American voters, with 73% of those polled saying they had an unfavorable view of China — up 26 percentage points from just two years ago.

Similar majorities back Mr. Trump’s argument that Beijing badly mishandled the COVID-19 outbreak and bears much of the blame for the current global pandemic.

“More generally, Americans see Sino-U.S. relations in bleak terms,” the pollsters wrote.

As the White House race heats up, both Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden are trying to paint the other as soft on China and unequipped to handle the major 21st-century challenge Beijing presents. At the same time, the global COVID-19 pandemic and mounting global criticism of China’s early reluctance to admit the true nature of the virus have drawn strong bipartisan criticism and sparked new anger with Beijing, and seems to have created an even deeper appetite among voters for a more sharp-edged policy.

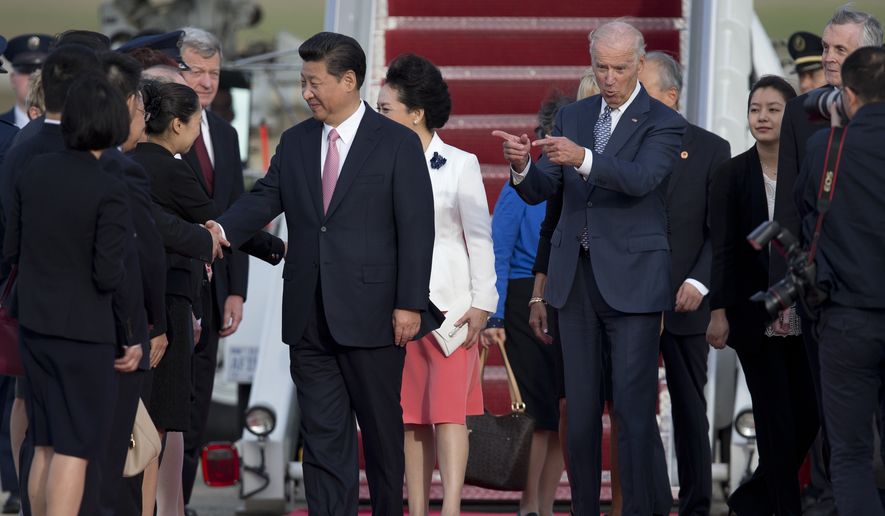

One of the clearest indications of new political paradigm has been how clearly and negatively both Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden now speak of Chinese President Xi Jinping. An early rapport as the two sides struggled to strike a new trade deal has given way for Mr. Trump to harsh criticism as the COVID-19 pandemic has exploded this year.

“I used to have a very good relationship with him,” Mr. Trump told Fox Sports Radio in an August interview. “I had a great relationship with President Xi. I like him, but I don’t feel the same way now. … I certainly feel differently.”

Throughout the Democratic primary campaign, Mr. Biden boasted about how long he’s known Mr. Xi and how that will enable him to better manage the U.S.-China relationship. But his word choice also has steadily evolved from tough diplomatic talk to a more blunt, almost Trump-esque style.

At a primary debate in February, for example, he called Mr. Xi “a thug.”

“This is a guy who doesn’t have a democratic-with-a-small-’d’ bone in his body,” Mr. Biden added.

A different emphasis

While Mr. Trump has emphasized aggressiveness in his public statements and private dealings with China, Mr. Biden’s political advisers have said the former Delaware senator will focus more on constructively engaging Beijing from a position of strength.

Republicans campaign strategists are hoping to use Mr. Biden’s own words from a May 2019 Iowa City event against him, when he belittled China’s economic prowess and asserted “they’re not competition for us.”

There’s also a belief around the world that a Biden presidency would bring a much less harsh rhetorical tone, even if some of the core policies remain the same.

“While the campaign rhetoric may well be dialed back post-election, when Biden will have no pressing electoral need to employ China-bashing language, the harder edge that has inserted itself into American foreign policy with respect to the PRC [will] likely remain, if not intensify,” Elena Collinson, senior researcher in the Australia-China Relations Institute at the University of Technology Sydney, wrote in a recent analysis.

A slightly less abrasive tone under Mr. Biden is perhaps one reason why U.S. intelligence assessments have concluded China would “prefer” if Mr. Trump is not reelected. Beijing also is keenly aware of Mr. Biden’s mixed record on U.S.-China relations and the former vice president’s broader malleability when it comes to foreign policy.

Mr. Trump has no doubts that the Chinese would prefer his opponent in the White House.

“If China makes a deal with the United States with Joe Biden in charge they would own our country,” he told a White House press conference in August.

While Mr. Biden has routinely criticized China throughout his long political career, he’s also often championed engagement. He supported China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization, a move Mr. Trump has repeatedly cited as an example of his rival’s poor judgment.

On the other hand, Mr. Biden in 1979 voted in favor of the Taiwan Relations Act, a bill that spelled out the relationship between the U.S. and Taiwan and specified American security commitments to the island. The Trump administration has built on that decades-old law by greenlighting numerous arms sales to Taiwan.

On economics, Mr. Trump throughout his nearly four years in office has focused on China’s trade practices, its theft of intellectual property, and other ways by which Beijing has tried to gain a leg up on the U.S.

The president has tried to address those problems by pursuing a broad new trade deal with China, instituting tough tariffs, and most recently by pulling the U.S. out of the World Health Organization amid accusations the group was too lax with Beijing during the crucial early days of the coronavirus crisis.

Mr. Biden has focused on many of the same underlying problems.

This year’s Democratic platform, for example, zeroes in on “unfair trade practices by the Chinese government, including currency manipulation and benefiting from a misaligned exchange rate with the dollar, illegal subsidies, and theft of intellectual property,” though the Biden campaign has strongly objected to the president’s use of tariffs and the broader way in which he’s approached trade negotiations.

Mr. Biden has echoed the president in opposing Chinese involvement in the construction of 5G and other technological infrastructure.

Such agreement on the foundational challenges facing Washington means that many tangible policies could remain in place regardless of who wins in November. The Biden campaign also has indicated that it will continue the Trump administration’s efforts to aggressively push back on China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea and elsewhere across the Pacific — though with a greater focus on regional partnerships.

“I would expect there to be more continuity than change,” said Charles Kupchan, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and former special assistant to the president on the staff of the National Security Council during the Obama administration.

“I’m reasonably confident in saying that a Biden administration would, very early on, [seek to] reassure allies,” he said. “When it comes to China, I think a relationship is in a difficult place, and is likely to remain there even if there is a change of power. And that’s because there are fundamental conflicts of interest on trade, on security, on human rights, on other issues that are not going away. I think that you’re likely to see some changes that I would call more changes in emphasis rather than in fundamentals.”

• Lauren Toms can be reached at lmeier@washingtontimes.com.

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.