OPINION:

There has been an excessive amount of talk about the U.S. Senate, Judge Merrick Garland, and the pending confirmation of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s replacement. It is probably time to clear away some of the chaff and focus on the wheat.

Democrats and their allies in the media have bored everyone complaining about the looming confirmation vote in the Senate and claiming that it is “unfair” in the context of how the nomination of Judge Garland was handled.

Let’s get serious for a moment.

Almost 600 years before Christ, the Ecclesia (“gathering of those summoned”) in Athens the first legislative body for which we have meaningful records was assembled and began to meet once a month to make decisions about civic issues. About 80 years later across the Adriatic, the Roman Republic was established, and the Roman Senate became its principal legislature.

In the intervening 2,500 years, there have been numerous legislative bodies across the globe, ranging from the United Nations to town councils. They all have one thing in common: They resolve questions by voting. In most instances the majority rules. In some, supermajorities are required. But in all instances, they aggregate preferences by voting. Coming to a decision by majority vote is the very essence of popular sovereignty.

In ancient Greece, they counted stones and sometimes broken pieces of pottery (“ostrakon,” from which we get “ostracize”). In Rome, they counted raised hands. Nowadays in Washington, the Senate calls the roll and records the yeas and nays that are called out by the senators.

What does this have to do with Judge Garland and the current nominee?

The U.S. Constitution is pretty clear on how judges happen: “[The president] shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint judges of the Supreme Court.”

It doesn’t say anything about vacancies near elections, or possible breaches of the Marquess of Queensberry rules, or historical precedent, or who is being mean to whom. The president shall nominate with the advice and consent of the Senate. That’s it.

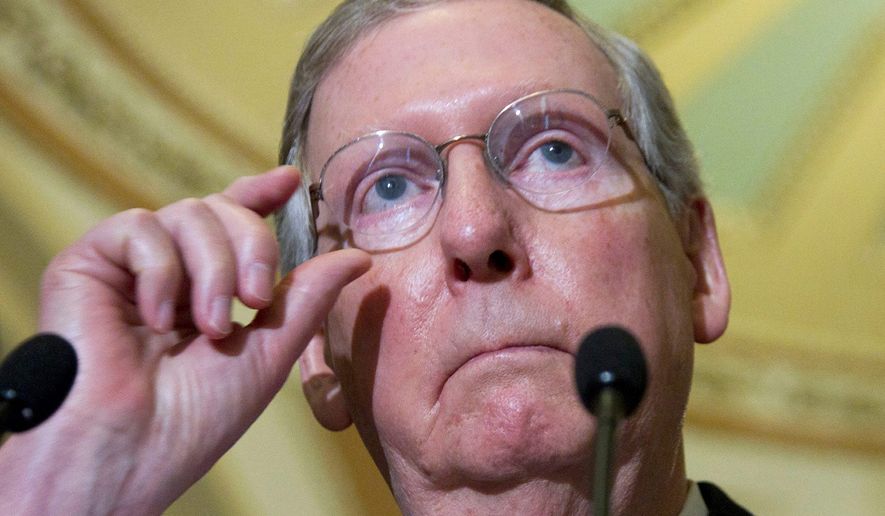

If those senators who supported Judge Garland back in 2016 had the votes to confirm him, the Senate would have confirmed him. It makes no difference whether Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was in favor of him or opposed to him or indifferent about him. If there were 50 votes in the chamber to confirm him, he would have become a Supreme Court justice. But there weren’t, so he isn’t.

In short, if you have the votes, you call the vote. That is a foundational, essential rule in any legislative body and has been for 2,500 years. If you don’t have the votes, you complain about the process.

We will know soon whether there are 50 votes to confirm President Trump’s nominee. If there are, the Senate will proceed to do so. If there are not, the chamber won’t. All the legislative maneuvering in the world won’t change that.

One final feature of the process is worth noting. There is a lot of discussion about whether it is better to have the confirmation vote before Election Day or after. Mr. McConnell knows better than anyone that (again) when you have votes, you call the vote. You don’t wait for something else to happen. He will call this vote at the earliest possible moment.

• Michael McKenna, a columnist for The Washington Times, is the president of MWR Strategies. He was most recently a deputy assistant to the president and deputy director of the Office of Legislative Affairs at the White House.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.