OPINION:

It was only earlier this month that the Trump administration announced a ban on teaching “Critical Race Theory” in federal agencies and already leaked documents show the CDC had planned to ignore the president’s executive order.

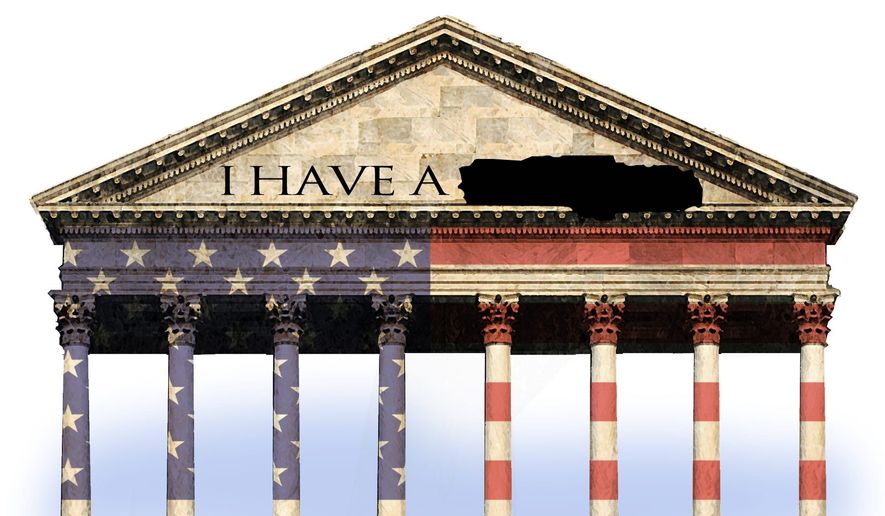

The White House responded by canceling the training outright Wednesday. And it’s a good thing because, although marketed to the public as having the goal of combating racism, Critical Race Theory, rooted in Black nationalist ideology, redefines “racism” and arguably has more in common philosophically with White supremacy than Martin Luther King Jr.’s style of anti-racism.

The Trump administration took the right step in banning federal funding of these views, which founder of Critical Race Theory Derrick Bell argued “must acknowledge [race] and move on to adopt policies based on what I call ‘Racial Realism.’” For what it’s worth, most prominent White nationalists also argue for race realism so this is not a new problem being nipped in the bud. Even before the field of Critical Race Theory was formally founded, the same damaging ideas it teaches infected the U.S. military.

In the late 1960s, the military suffered repeated and brutal incidents of racial violence. This led to escalating efforts to stop these kinds of conflict. In 1971, the Department of Defense issued directive 1322.11, which established “a comprehensive educational program in race relations for all members of the military services and provides guidance for developing race relations training programs and related activities within the army.”

That order led to the formation of an organization named the Defense Race Relations Institute (DRRI). Between 1971 and 1974, every military employee was mandated to receive 18 hours of race relations seminars, with the vast majority of seminar teachers trained by the DRRI.

The DRRI based large sections of its curriculum around the teachings of White “anti-racist” educator Robert Terry. Terry, whose 1970 book “For Whites Only” was assigned by the DRRI, taught militant Black separatist ideas to White audiences. In particular, his views were influenced by Stokely Carmichael, the man who coined the term “institutional racism” and who moved from America to Guinea with the goal of founding a pan-African Marxist-Leninist Black ethnostate.

Despite polling demonstrating separatist views were fringe within the Black community, Terry taught them as if they were representative of what the entire Black community desired. Terry wrote, “[e]fforts to overcome alienation by assimilating blacks into the mainstream of American life have presupposed the mainstream as the desirable standard. Equality with whites is the goal. What the liberal does not understand is that equality with whites is a racist goal … Integration has been the key word in the liberal’s racist vocabulary.”

Terry’s philosophy of “New White Consciousness,” explicitly advocated by DRRI, included the notion that “None of us [White people] escapes being racist in American society.” To Terry and his intellectual followers, all White people were racist by this idiosyncratic definition and the best a White person could be was an “anti-racist racist.”

Commanders regularly criticized DRRI trainings, along with the Army’s contemporaneous affirmative action policies, for “weakening the chain of command, decreasing mission effectiveness, and lowering standards in general.” At least one commander complained that “EOT [Equal Opportunity Treatment] programs are causing race problems — the more you talk about racial differences and the more you put emphasis on them, the more trouble you’re going to have. Putting emphasis on the problem just exacerbates it.”

While this point of view was reported to race relations leaders, the critique did not appear to be taken seriously by the DRRI, which advocated for expanding race relations training outside of service members themselves to service members’ children and even their wives. Officers were also advised that since “vocal militants … have considerable influence over peers … for an effective race relations program, these men should be brought into the formal power structure.”

Thankfully, this radical program of the DRRI would not last. Commanders accused the DRRI of brainwashing and creating “race militants” who were “subvert[ing] the normal activities of the military.” The Pentagon launched an investigation into the DRRI and concluded that it was “overzealous in its initial training methods” and asked that it “modify its approach so that individuals leaving the institute would not appear too militant.”

Additionally, the House Armed Services Committee reported that race relations trainings might have weakened military discipline, closed all branch-specific race relations schools and dropped 700 race relations instructors and managers from the budget.

However, the DRRI still exists; in 1979 it was renamed the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. It still teaches radical views that inflame racial division to this day.

The story of the DRRI is a sad one. Racial healing truly was needed in the military and society, especially back then. The military had the option of teaching staff the colorblind philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr., that we should forever bury race as a category that divides. Unfortunately, racial trainings, both then and now, have served only to help bury King’s dream.

• Joseph (Jake) Klein is a filmmaker at the Capital Research Center, the founder of its Dangerous Documentaries project and the author of the upcoming “Redefining Racism: How Racism Became “Power + Prejudice.” You can find him on Twitter @JosephJakeKlein.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.