OPINION:

The media is placing an unfortunate amount of emphasis on results from single surveys and single survey questions about the presidential election. Any specific survey can be wrong, and any survey question can be taken out of context.

Survey results are best understood as a story — a story that voters are trying to tell us, rather than as grist for the media mill.

At this point in the campaign, one-time surveys are less than ideal for a few reasons. First, each day provides new information for voters to process, which surveys sometimes capture and sometimes don’t. Second, traditional surveys typically measure sentiments that are four or five days old. That’s fine most times, but in the waning days of a campaign, it is unacceptably dated. Third, campaigns prefer to conduct surveys every day toward the end of a campaign so they can test messages and responses to events in as close to real time as possible.

For these reasons, campaigns typically switch to tracking surveys in the final few weeks and months of a campaign. In tracking surveys, researchers ask a set number of respondents (usually 300-500) each day the same set of questions — For whom are you voting? What is the most important issue? They then take these responses and combine them into the responses for the previous three or four days and create a rolling average.

This tracking allows a campaign to follow trends and trajectories, which in turn allows them to allocate time and money in the closing, usually frantic days of the campaign.

As painful as it is for me to acknowledge this, the University of Southern California has the best tracking survey, the “Understanding America Study.” In 2016, it predicted that Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton would win the popular vote by 2%. She won by 1.8 percentage points.

This year, its tracking results are … interesting.

USC has about 6,000 respondents in its response panel this year. Rather than random sampling the universe of potential voters, the survey takers are relying on a panel that reflects what they believe to be the likely composition of the electorate on game day.

Each day, they ask about 350 respondents from the panel the same set of questions and then make the seven-day and 14-day rolling averages of those responses available on their website.

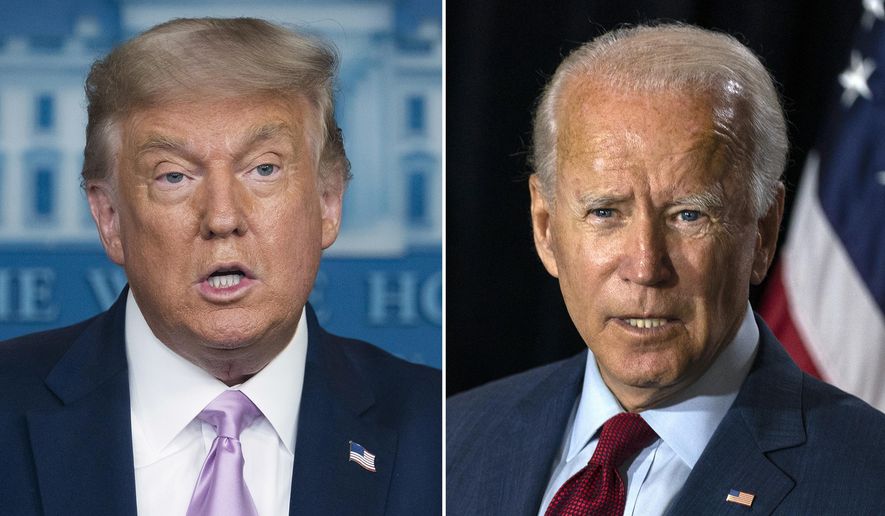

When asked about for whom they intend to vote, respondents have given Democratic candidate Joseph R. Biden a consistent 7- to 10-point advantage. However, when respondents are asked for whom their friends and family are voting, the results are narrower — usually tilting toward Mr. Biden, but only in the 5-point range. Moreover, when respondents are asked to anticipate for whom their state will vote, the results drop down to a very close margin — 1 or 2 points — for Mr. Biden.

You can interpret those results in different ways, but the most likely interpretation is that while some voters — panelists — are clear about who they prefer, they are hearing a lot of conversation from friends, families and neighbors that suggests the race is closer and probably more uncertain than the one-off surveys indicate.

Will Mr. Biden win the popular vote? Probably. Will it be close? Probably. Are voters sure that everyone is set with respect to their vote? Not yet.

• Michael McKenna, a columnist for The Washington Times, is the president of MWR Strategies. He was most recently a deputy assistant to the president and deputy director of the Office of Legislative Affairs at the White House.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.