OPINION:

There was a simplicity to the Cold War. Free peoples, and those who aspired to that status, were threatened by communism, a totalitarian ideology aggressively propagated by the Soviet Union, an expansionist empire. The Cold War also was a “forever war”: No one knew when it would end.

And then, of course, it did end, the way a character in Ernest Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises” describes having gone bankrupt: “Gradually, then suddenly.”

After that, Americans took a holiday from history, one abruptly brought to a halt on Sept. 11, 2001. Over the years since, other threats to the U.S. have emerged or, more precisely, been widely (though not universally) recognized. The response of American leaders has left much to be desired.

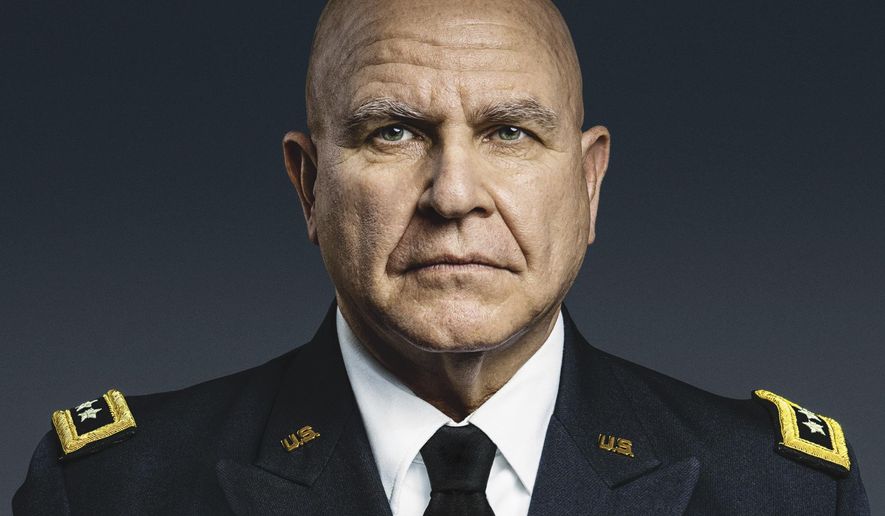

During the 13 months he served as National Security Adviser to the commander in chief, H.R. McMaster made a strenuous effort to bring what he calls “strategic competence” to the Rubik’s Cube that is national security in the 21st century.

He has now distilled his thinking into a book. It’s titled “Battlegrounds” (note his use of the plural) and subtitled: “The Fight to Defend the Free World” (note his conviction that there is, still, a Free World, and that it is worth defending).

Brief background: Lt. Gen. McMaster served 34 years in the U.S. Army (including deployments to both Iraq and Afghanistan), picking up a doctorate in history along the way and teaching at West Point. He’s currently the Fouad and Michelle Ajami Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution and Stanford University, and chairman of the board of advisers at FDD’s Center on Military and Political Power (CMPP).

“Battlegrounds,” Gen. McMaster writes in the preface, “is not the book most people wanted me to write.” That book would have been a gossipy tell-all, focusing on Donald Trump’s unique persona.

Instead, his purpose was to “help transcend the vitriol of partisan political discourse and help readers understand better the most significant challenges to security, freedom, and prosperity.”

Gen. McMaster begins by identifying a serious flaw in much of that discourse: “Strategic narcissism,” which he defines as “the tendency to view the world only in relation to the United States, and to assume that the future course of events depends primarily on U.S. decisions or plans.” This can result in either “overconfidence” or “resignation,” postures that “share the conceit of attributing outcomes almost exclusively to U.S. decisions and undervaluing the degree to which others influence the future.”

Among the examples he cites: President Bush’s underappreciation of the risks of action when he invaded Iraq in 2003, and President Obama’s underappreciation of the risks of inaction when he withdrew all U.S. forces from Iraq in 2011.

The corrective to strategic narcissism is “strategic empathy,” defined as “the skill of understanding what drives and constrains one’s adversaries.”

It’s comforting to believe that our adversaries want security, freedom and prosperity as much as we do; that they prefer compromise and cooperation to confrontation. But rarely is that the case. China’s rulers provide a vivid example.

One year after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, President George H.W. Bush declared: “As people have commercial incentive, whether it’s in China or in other totalitarian countries, the move to democracy becomes inexorable.” But it doesn’t.

Arguing that China be admitted into the World Trade Organization. President Clinton asserted that Beijing “is agreeing to import one of democracy’s most cherished values: economic freedom.” But Beijing wasn’t.

President Obama’s China polices, Gen. McMaster writes, rested “on the belief that engagement would foster cooperation.” But that’s not what happened.

Breaking with this tradition, the 2017 National Security Strategy, written under Gen. McMaster’s direction and signed by President Trump, recognized that China’s rulers view themselves as our adversaries and rivals for global leadership.

Gen. McMaster also understood that Vladimir Putin’s Russia has been “pursuing an aggressive strategy to subvert the United States and other Western democracies.” Pushing a little button labeled “reset” was never going to change that.

Though the Islamic Republic of Iran has been implacably hostile to the United States since its founding in 1979, Ben Rhodes, one of President Obama’s top deputies, assured Americans that the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action would produce “an evolution in Iranian behavior” as the clerical regime became “more engaged with the international community.” That was a pipe dream.

One administration after another has either ignored or addressed ineffectively the metastasizing threat posed by the dynastic dictatorship in North Korea.

Lack of strategic competence has been on display in Afghanistan, too. There, Gen. McMaster writes, after the “military successes of 2001, a complex competition ensued with an unseated, but not defeated, Taliban; an elusive Al Qaeda; new terrorist groups; and supporters of those terrorist organizations, including elements of the Pakistan Army, a supposed ally.”

He describes what happened next: “Paradoxically, a short-war mentality lengthened the conflict. The war had lasted nearly two decades, but the United States and its coalition partners had not fought a two-decade-long war. Afghanistan was a one-year war fought twenty times over.”

I haven’t space here to summarize all the shifts in strategic thinking Gen. McMaster would recommend to any American commander in chief hoping to prevail on today’s multiple battlegrounds. Suffice to say he grasps that when America appears weak, America emboldens its enemies. He knows that enriching adversaries doesn’t appease them. He believes military strength can deter. And when deterrence fails, and conflict is inevitable, military strength becomes even more essential.

Gen. McMaster also cautions that isolationism — call it “restraint” or “responsible statecraft” or “opposition to forever wars” if you like — is a siren song. As Leon Trotsky almost said: You may not be interested in national security, but national security is interested in you.

• Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and a columnist for The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.