OPINION:

Editor’s note: This is part of a series “To the Republic: Rediscovering the Constitution.” Click HERE to read the series.

The Constitution, as solid as it is, ultimately relies on those who make and execute the laws to do so faithfully and with good intention.

We all know the story of the birth of the Constitution, when a matron of Philadelphia asked Benjamin Franklin if the delegates had produced a monarchy or a Republic. “A Republic, madam, if you can keep it.”

The durability of the new Republic relied and relies on internal mechanisms that modulate and moderate the passions of democracy and restrain the natural human inclination to abuse power.

Among these mechanisms is a Senate whose state-focused perspective forms a check on the population-driven House, an Electoral College that protects rural states from being drowned out completely in the election of the president, and a Supreme Court that hovers above the fray, assuring adherence to the Constitution and the impartial continuity of law.

This balance has endured through the centuries and has acted as a baffle on the waves of public passion that wrecked earlier experiments in democracy.

The societal sentiments that supported the Constitution and its executors and guardians survived because a reverence for the document and its underlying purposes was passed from generation to generation. All sides had an interest in preserving both the document and its purposes because of the balance and stability they guarantee. As long as these sentiments held, whoever lost an election could confidently expect to prevail when the political winds changed once again.

This balance of power has made America the most stable and durable democracy established in the modern world. Unfortunately, this election cycle promises to be challenging to both the Constitution and the republic it formed. If one party sweeps the White House, Senate, and House in this election, many already have announced an intent and a design to sweep it away for all time.

The challenge will begin with the abolition or dismemberment of the Senate’s cloture rule. Though not a constitutional provision, it is an ancient parliamentary device that assures the minority has a say in the Senate’s deliberations. It is based on the core principle of our Republic — the majority rules, but the rights of the minority are protected and their voices are heard. The minority has a vital role in pointing out flaws, offering alternatives, and persuading the majority. Cloture originally insured that debate must continue while the minority had something to say.

There is no doubt that modern usage of the rules of cloture no longer protects debate but impedes it and are badly in need of reform.

But leaders of one party don’t propose to repair cloture, but rather to abolish it, leaving the minority with virtually no say into the decisions of the Senate, rendering it a mere reflection of the House rather than a check upon it.

Once cloture is abolished, we can expect a rapid and catastrophic chain of events.

Some Democrats have made their intention to pack the Supreme Court graphically clear. The Constitution leaves it to Congress to set the number of Supreme Court seats, yet since 1869 Congress has resisted the temptation to tinker with the central referee of our political institutions, even as popular majorities have shifted dramatically from election to election.

The Court’s moral authority stems from the fact that its members serve life terms and span many administrations. Adding seats to achieve a political outcome would destroy its credibility and the stability it guarantees.

Some Democratic leaders have also made clear their intention to pack the Senate with new states, and the House already voted this year to admit the District of Columbia with two new Senate seats. Simple majorities can admit territories as States or even divide reliably States (with their consent). Even during the contentious years approaching the Civil War, neither side sought to take advantage of this power. That may change.

Next to go will be the Electoral College. It could be as simple as a majority of both houses ratifying the so-called “National Popular Vote Interstate Compact” — which seeks to instruct presidential electors to ignore the votes cast in their own states, and instead cast their votes with the national popular vote. That would effectively leave rural States at the mercy of the more populated coasts with virtually no voice in selecting future presidents. With a packed and partisan Supreme Court there would be no one to stop them.

Thus, in a relatively short time, the Constitution may bear little resemblance to the bulwark that has assured a stable, equitable, and balanced national government; a government that adheres to the Constitution, refrains from riding roughshod over the minority (on any question) and the rural states, and checks the excesses that human nature would otherwise produce.

Lincoln once warned that “if destruction be our lot, we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of free men, we must live for all time, or die by suicide.”

He was, in his way, noting the importance of tradition and restraint. The Constitution is no sturdier than the intentions of those who operate under its constraints.

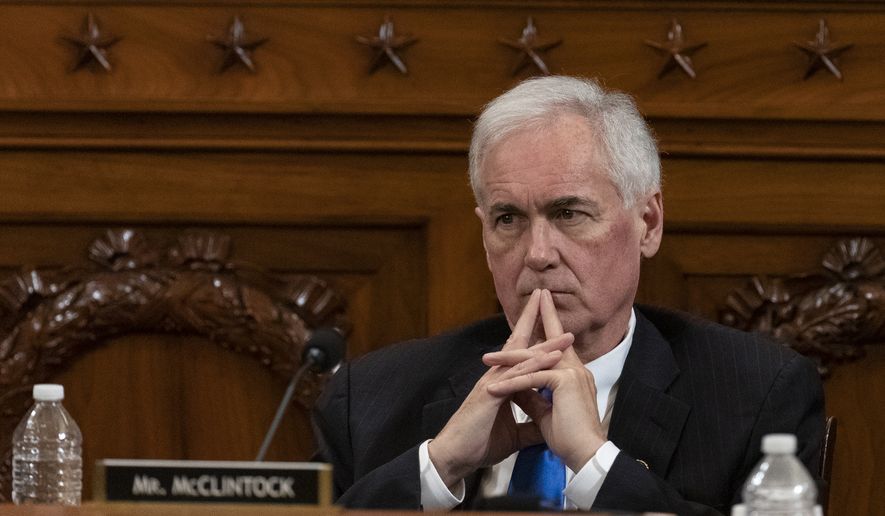

⦁ Rep. Tom McClintock, California Republican, serves on the House Judiciary Committee.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.