Postal employees in New Jersey and Florida have been charged this month with dumping or blocking the delivery of mail-in ballots, and a third employee was fired after investigators say they found more than 100 mail-in ballots dumped in Kentucky.

In West Virginia, a mailman pleaded guilty over the summer to meddling with ballot requests in the presidential primary, switching voters from Democrat to Republican.

In central Virginia, collection boxes outside six post offices were ransacked this month, and election officials worry that ballots may have been taken.

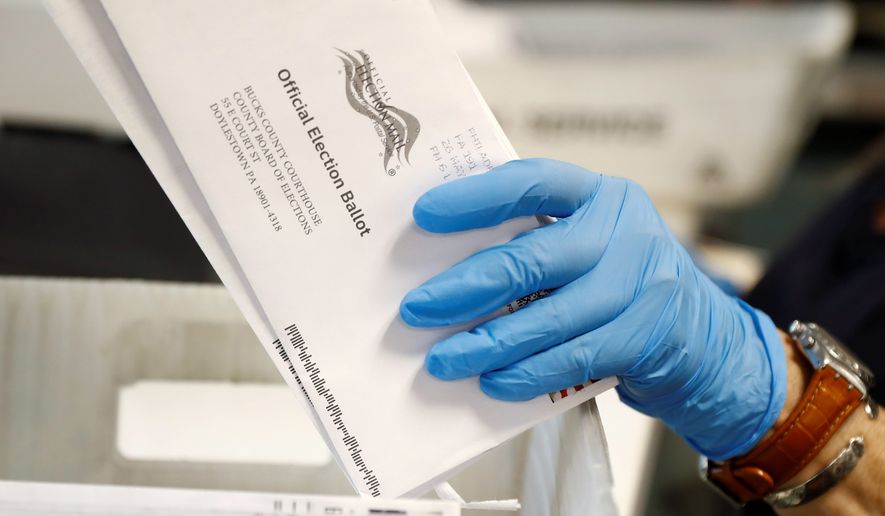

While most of the attention paid to the role of the U.S. Postal Service this election year has been focused on whether it can handle the volume and timing of ballots, the spate of incidents suggests there are other reasons to worry about the Postal Service as a weak link in what is expected to be a record number of vote-by-mail ballots.

“If you want people to be disenfranchised, make them all vote by mail,” said J. Christian Adams, a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. “Ballots get lost, ballots get destroyed, ballots get hidden by postmen. The worst thing you can do is decentralize the process.”

The matter has taken on urgency this year as officials in both Republican- and Democrat-led states rush to offer voters more options during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some states expanded in-person voting, but by far the most popular change has been encouraging voters to cast ballots by mail.

In some states, officials are mailing ballots to every voter. Other states are making people request a ballot but no longer require a reason for absentee voting. Still others have scrapped witness signature requirements, figuring that to make voters have contact with another person during the pandemic is unsafe.

Voters have set records for mail-in ballot requests in jurisdictions across the country.

President Trump is less excited. He says mail voting will be fraudulent.

Experts doubt that the presidential election could be swung by mail-in ballot fraud, though it could play roles in close races down the ballot.

Another problem is emerging as voters and politicians alike worry that the postal system won’t be able to handle the load.

Jurisdictions that have experience with all-mail elections warn others to be ready for tens of thousands of rejected ballots based on signature mismatches or other ballot errors. During California’s presidential primary in March, more than 100,000 ballots, about 1.5% of the total, were disqualified.

The Postal Service is gaining attention as the number of mishaps grows.

The latest charges were filed this week in Florida. Crystal Nicole Myrie, 31, was charged with interfering with an election after a Postal Service inspector general investigator discovered a ballot intended for a voter that she kept in her personal vehicle, along with gift cards, political flyers and other mail.

Under Florida law, the person the ballot was intended for would not have been able to cast a ballot, even in person, without bringing the mailed ballot to be canceled.

In Bergen County, New Jersey, a mail carrier was charged with mail theft this month after authorities noticed mail missing on his route. Investigators found 99 mail-in ballots, en route to voters, dumped.

In Kentucky, a federal investigator announced that a postal employee was let go after dumping 112 absentee ballots.

Each of those cases involved ballots on the way to voters.

In the West Virginia case, a mail carrier changed primary ballot requests from Democrat to Republican. He admitted to attempted election fraud in July.

In Texas, prosecutors have brought charges in two cases of absentee ballot fraud.

In one instance, they accused a county commissioner of running a scam to harvest absentee ballots from people who were ineligible to vote that way. The commissioner won his seat in 2018 on the strength of those ballots.

In the other case, a mayoral candidate stands accused of forging dozens of absentee ballot requests in November’s election.

In every case, mischief is possible only because the ballots leave what has traditionally been a closed election system, with a voter showing up at a specified precinct, marking a ballot and then submitting it. In no instance did the ballot leave the polling place.

With mail voting, however, the chain of custody is murkier. Postal employees, other household residents, caretakers or anyone else with access to a home or mailbox could touch the ballot. Some states allow ballot harvesting, by which someone collects ballots from voters and submits them on their behalf.

John C. Fortier, director of governmental studies at the Bipartisan Policy Center, said there has long been tension between the desire for voting convenience and election integrity. He said mail-voting is popular, and convenience is winning that debate.

Some states have done it well. Colorado runs all-mail elections. Every voter is sent a ballot and can cast it either by sending it through the mail or dropping it off. They can also show up and vote in person.

The state has secure drop boxes, bipartisan teams that collect the ballots and signature matching to verify the voter. Colorado also has a live connection from polling places to voter databases, so officials will know when someone who shows up to vote in person has already cast a ballot, Mr. Fortier said.

Voters can also go online to see whether their ballot has been accepted.

“I’m not sure all of these issues can be mitigated, but some can be mitigated by a really well-run election process,” he said.

The problem is that so many states are rushing to expand mail voting. They may be cutting corners, and they are throwing a new system at the electorate, too.

“Voters themselves actually do have problems voting in a new way, voting by mail. There are more ways you can have your ballot thrown out,” Mr. Fortier said.

He said that’s a larger issue than Postal Service hiccups, which he called “marginal” in terms of the total number of votes cast and counted in this election.

The Washington Times reached out to several mail-ballot voting advocates, but they either said they were too busy or didn’t respond.

Neither did the Postal Service or its inspector general’s office, which is investigating the mishaps, though the official who announced the Kentucky employees firing insisted in a statement that such incidents are “exceedingly rare.”

Mr. Adams said there is no way of knowing because there is no telling how many go undetected or unreported.

He said the Texas cases should serve as a wake-up call.

“I’ve always had ideas about what could happen. If those facts are accurate, it pushes the envelope,” he said.

Mr. Adams said pitfalls from mail-in voting are beginning to hit home with voters. Polling suggests that while it’s still popular, the number of people saying they plan to vote by mail has shrunk compared with over the summer.

Even some Democratic officials are worried about disqualified ballots, which according to research are more prevalent among minority and younger voters — key groups in the party’s coalition.

“This is a big ’I told you so’ moment for me,” said Mr. Adams. “They may lose the election over their insistence on this.”

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.