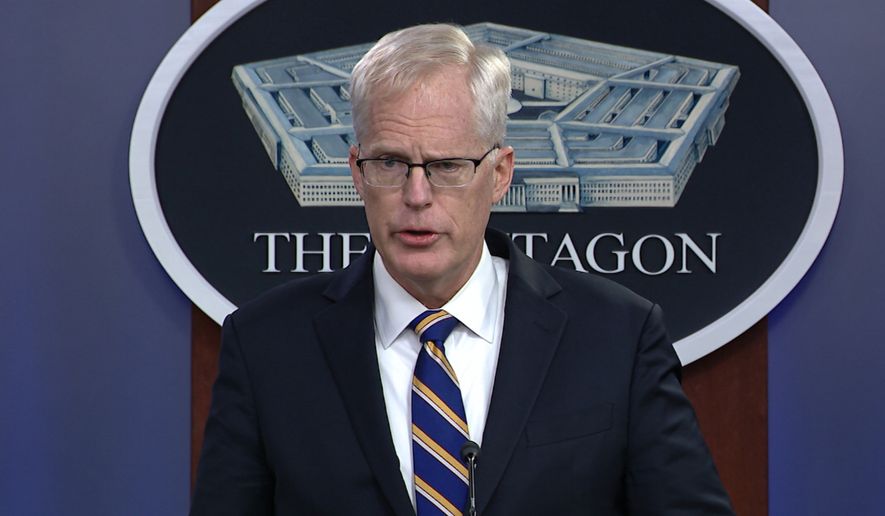

A surprise trip by acting Defense Secretary Christopher Miller to Somalia over the Thanksgiving weekend is fueling speculation that President Trump may soon pull the U.S. out of an “endless war” in the Horn of Africa — but there are growing fears that a hasty American exit could embolden the Islamic extremist group al-Shabab and destabilize the entire country at a delicate political moment.

The roughly 700 U.S. troops currently in Somalia primarily conduct counterterrorism missions and train Somali forces while also helping to coordinate an American anti-terror drone war that has grown more aggressive throughout Mr. Trump’s four years in office. The air campaign has kept al-Shabab — an al Qaeda affiliate estimated to control as much as 25% of Somali territory — in check, but America’s limited military engagement has proven inadequate to fully defeat the group or to spur peace negotiations with the struggling government in Mogadishu.

Faced with that reality, Mr. Trump reportedly is on the verge of ordering all U.S. forces to leave Somalia. Such a move would come on the heels of major troop drawdowns in Iraq and Afghanistan, scheduled to be completed just days before presumptive President-Elect Joseph R. Biden assumes office on Jan. 20.

While some American forces almost surely would remain in neighboring countries and U.S. drones would continue bombing al-Shabab targets across Somalia. But as in other U.S. deployments in hot spots around the globe, Mr. Trump is taking flak from critics who say pulling out is worse that staying put.

Analysts warn that a U.S. withdrawal would be cast by terror groups as a major victory and serve as a serious public relations and recruiting boost. The potential exit also would come as the fragile Somali government gears up for presidential and parliamentary elections in the coming months, and a significant uptick in violence could derail those contests and spark a new wave of instability.

“The short-term ramifications are significant,” said Katherine Zimmerman, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who studies the region. “Rapid gains by al-Shabab as Somali units collapse under pressure and the counterterrorism operation tempo drops; al-Shabab claiming victory over the U.S., joining what might soon be a choir that includes the Taliban and perhaps the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria; and the shift in focus toward security concerns over the upcoming [Somalian] election. Limited bandwidth across the board will mean the elections [do] not get the attention they need.”

Mr. Miller offered few clues as to the future during his brief trip to Somalia, where he celebrated Thanksgiving with U.S. troops.

“Honored to celebrate Thanksgiving with U.S. military personnel at Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti and in Mogadishu, Somalia, and give thanks for the sacrifices our service members and their families make to protect our freedoms and the American way of life,” he said in a Twitter statement during the trip.

Mr. Miller was installed after the president fired former Defense Secretary Mark Esper earlier this month. Mr. Miller is widely viewed as much more amenable to Mr. Trump’s desire to pull U.S. troops out of conflicts in the Middle East and Africa in quick fashion, and even engaged in some clandestine diplomatic outreach to al-Shabab leaders as head of the National Counterterrorism Center before getting the Pentagon post.

The initiative reportedly angered Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and was promptly shut down.

In Somalia, terrorism is just one piece of a complex equation. The historically difficult Somali electoral process already appears in turmoil this week after the Somali government expelled the ambassador from Kenya, alleging that its African neighbor is interfering in elections in Jubbaland, one of the Somalia’s semi-autonomous provinces.

Successful elections and a relatively stable central government has been at the core of America’s exit strategy. U.S. military officials long have planned to turn over leadership in the fight against al-Shabab to the Somali government by next year, though that timeline is now in doubt even if American troops remain inside the country.

Specialists say an American withdrawal also could lead troops with the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) to take a step back, giving al-Shabab even more freedom to operate.

“Under the new U.S. military plans, attack drones will still fly from Kenya and Djibouti. But the risks of tragic and politically exploitable civilian casualties will grow, and the air strike frequency is likely to decrease,” Vanda Felbab-Brown, director of the Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors at the Brookings Institution, wrote in a recent analysis.

“Fearing al-Shabab, AMISOM may bunker up in garrisons even more and reduce the number of bases, thus weakening anti-Shabab militias,” she said.

Some former military officials warn that an emboldened al-Shabab represents a very real threat to U.S. national security interests at home and abroad.

“The reality is, on the ground in places like Somalia and Afghanistan, there are still terrorists who would do us ill, and I want to play, actually, the game on their turf, and not play it here,” retired Adm. Mike Mullen, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said on NBC’s “Meet the Press” program on Sunday.

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.