MOLINE, Ill. (AP) - Orin Rockhold of Milan was leafing through his Feb. 7 New York Times when he turned to a full-page obituary for internationally acclaimed American artist Beverly Pepper.

Rockhold knew that name well.

His mind leaped back 40 years to 1981 when he and co-workers at the John Deere Foundry in Silvis spent months helping Pepper create more than a dozen “monumental” (big) metal sculptures ranging from nine to nearly 24 feet in height.

Pepper was working as a resident artist under the auspices of the Visiting Artists Series, and Deere & Co. turned over nearly its entire foundry to Peppers to help create her art.

This included the services of its engineers, draftsmen, pattern makers, foundry men, machinists, welders, assemblers and technicians.

“I think that’s about all the foundry did when she was there,” Rockhold, a pattern maker, said days after her death was announced, still sounding somewhat surprised. “This was no cheap project.”

Under the chairmanship of William Hewitt, the unprecedented collaboration was Deere’s contribution to art and the community. Other companies that contributed were Williams White Co., Keller Pattern Shop and Frank Foundries.

Four of Pepper’s pieces remain in the Quad-Cities; other locations include the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, the Barcelona Museum of Contemporary Art, the Albertina Museum in Vienna and the Power Institute of Fine Arts in Sydney.

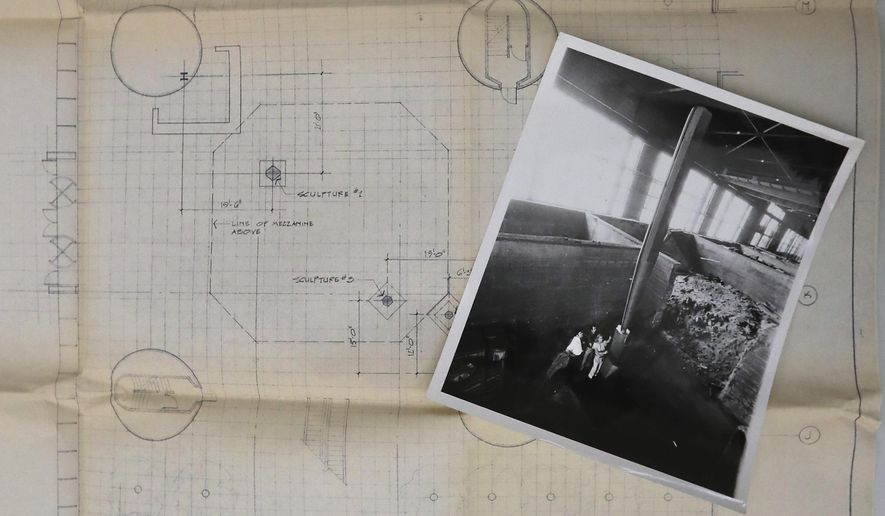

In Silvis, Pepper made sketches, draftsmen transferred them to graph paper with dimensions, then pattern makers used those specifications to make wood scale models. From there, molds were made and molten iron was poured into sand casts.

It helped that Pepper knew how to weld - not a common skill for women or artists of the time - and she thoroughly understood the casting process.

But production had many challenges.

“Producing the larger than usual castings required improvisation where standard equipment and processes were not adequate,” according to an article by Robert S. Lee in the March 1982 issue of Modern Casting Magazine.

“Larger than existing flask (the frame for a mold of sand) equipment was needed. … Ladle capacities required pouring at times with two and three ladles. Artistic, structural, molding and capacity requirements were sometimes in conflict.”

Assembling the works brought more challenges, according to Lee. “Portability required disassembly into components that could be transported in freight elevators to indoor exhibitions. This called for hidden machined joints and fasteners,” Lee wrote.

In addition to Silvis, Pepper also had projects underway in New Jersey and Texas, so she would come and go. While here, she stayed at the homes of company executives, or at Rockhold’s home, or hotels, Rockhhold said.

As part of her residency, groups could visit the foundry to watch her work, and she gave talks in the community. Photos and videos were taken as her art progressed and were made available for showing in schools.

“There were times when workers were surrounded by cameras, lights, interviewers and just the curious,” according to Modern Casting.

At the end of her residency, 10 pieces made at the foundry were exhibited at the Davenport Art Gallery, the predecessor to the Figge Art Museum, Aug. 20-Oct. 4, 1981, under the title “The Moline Markers.”

When the show was over, they went to her New York gallery. Four others that were made in Silvis but were not part of “The Moline Markers” stayed in the Quad-Cities.

Pepper’s work is what a layperson might call “abstract.” The pieces don’t look like people or animals, although several casts in Silvis resemble giant tools, including a file, with serrated edges, and a screwdriver.

In an exhibit catalog accompanying the show in Davenport, art gallery director Larry Hoffman noted that her sculptures exhibit “linear edges, clean planes and intervals of negative space … combined with a sensuous tactile surface which command artistic authority.”

Phyllis Tuchman, art historian and critic, wrote that the pieces “seem to function as beacons, sentinels or totems.”

She also noted that they appear “thin and reedy,” and “if one were to categorize these structures, one would dub them a type of archeological minimalism.”

The exhibition catalog is among the considerable memorabilia Rockhold collected about this once-in-a-lifetime project.

As he talked about his role, he unpacked a large plastic storage tote filled Pepper’s sketches and notes, the graph-paper designs, newspaper clippings and photos.

“They put me as the lead man … to get it done the way she wanted it done,” Rockhold said.

Pepper “was real easy to work with,” he added. “I just followed her (direction), you know? I had a good understanding of what she wanted and she knew that.”

The feeling of camaraderie apparently was mutual.

In a letter to William Hewitt, chairman of the board, dated Aug. 27, 1981, Pepper wrote that, “I certainly could not have overcome countless obstacles, initially unseen, which came upon us in the development of the work, were it not for the special and generous help from the marvelous men and women with whom I worked.”

At the end of the catalog accompanying the exhibition, Pepper wrote her thanks to the men who turned her sketches into living, breathing art.

“I’d like to speak of the foundry men who worked on the project and of those in particular who became eating and drinking buddies as well as guardian angels,” she wrote.

She identified 14 by name, including Rockhold.

Rocky, as she called him, “worked closely with me, … overcame the seeming impossible, … followed through when I wasn’t present and understood what inner realities I was searching for,” she wrote.

The catalog concludes by saying that “we (the people behind the project) are hopeful that this collaborative project has served as a model for expanding cultural endeavors of the major arts organizations within the community…

“It has been an ambitious and noteworthy project.”

___

Source: The (Moline) Dispatch, https://bit.ly/2vvVi6K

Please read our comment policy before commenting.