These are “sorry” times.

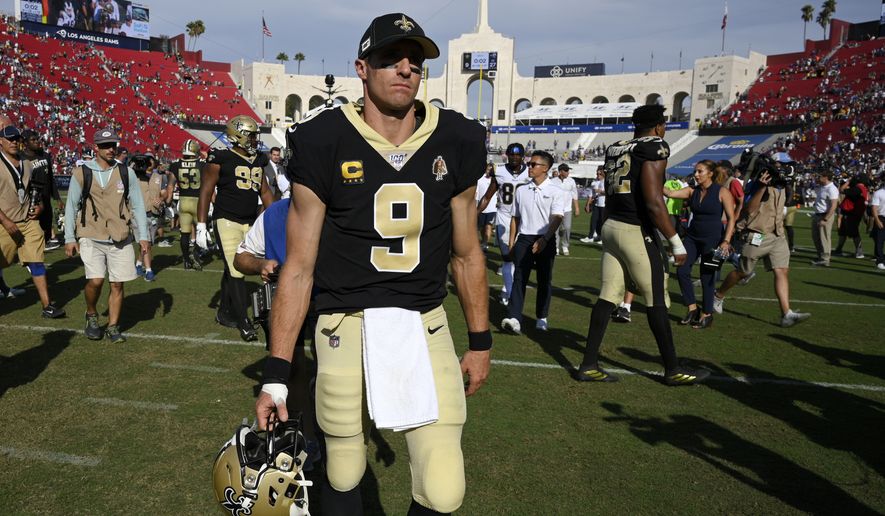

A Google News search for “apology” over the past week reaps reams of contrition, including NFL quarterback Drew Brees’ wife’s apology for his remarks about kneeling during the national anthem and a Fox News apology for a graphic showing how the stock market rose after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

But apologizes, whether they are earnest mea culpas or cynical rhetorical devices, must either address the perceived victim or else fall flat in self-servitude, a leading psychological researcher says.

“Public apologies from well-known figures like this are really difficult to do in a convincing way,” said Cynthia Frantz, professor of psychology and environmental studies at Oberlin College. “There are just so many competing reasons explaining the apology.”

In large part, apologies are in high demand.

On Saturday, a Fox News host apologized for a graphic presented a day earlier that linked upticks in the stock market after the widely publicized deaths of black men such as King in 1968; Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014; and George Floyd in Minneapolis on Memorial Day.

“Last night, Fox News Channel aired an infographic attempting to show the stock market on occasion gained ground in the midst of turmoil, civil unrest and even tragedy,” said anchor Eric Shawn. “In trying to make that point, the program ’Special Report’ failed to explain the context of the times we are living in and should not have used that graphic.”

In an emotional Instagram post Saturday, Brittany Brees, wife of the New Orleans Saints quarterback, quoted a Bible verse and wrote, “To say ’I don’t agree with disrespecting the flag,’ I now understand was also saying I don’t understand what the problem really is, I don’t understand what you’re fighting for, and I’m not willing to hear you because of our preconceived notions of what that flag means to us.”

Days earlier, her husband apologized for comments about former NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who would silently take a knee during the national anthem to raise awareness about police brutality. Brees retracted his remarks in an Instagram post and video after weathering criticism from teammates and NBA star LeBron James.

The anatomy of an apology, according to social science research, suggests some beta-level requirements: use of the word “apology,” public accountability and showing the bad action won’t continue.

Ms. Frantz said the apology issued by Brees succeed on some fronts — by specifically naming those he offended, including the general New Orleans community and black residents — but failed by returning to talk about himself.

Getting an apology right is a taller task when apologies are not between individuals but rather among a group or groups of people. Last week, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell issued a video admitting the league erred in dealing with peaceful protests by players in past seasons, including fines against teams for players who knelt during the anthem.

“We, the National Football League, admit we were wrong for not listening to NFL players earlier and encourage all players to speak out and peacefully protest,” Mr. Goodell said in his message. “We, the National Football League, believe that black lives matter.”

The NFL got slammed by players, a Hollywood director and even President Trump for a statement that was considered as either too-little, too-late or an appeasement to a fringe element that despises America.

“Could it be even remotely possible that in Roger Goodell’s rather interesting statement of peace and reconciliation, he was intimating that it would now be O.K. for the players to KNEEL, or not to stand, for the National Anthem, thereby disrespecting our Country & our Flag?” Mr. Trump tweeted Monday.

Another critical ingredient in an apology is credibility, said Ms. Frantz. For white people, especially on the subject of race, an apology can risk sounding tired or just more talk after decades of discrimination.

“For black people, they’ve heard white people for centuries say something needs to change … and nothing has gone down differently,” said Ms. Frantz. “It’s a lot of mental gymnastics going on.”

Even the best of intentions can have a way of backfiring. The founders of the social justice group Campaign Zero apologized this week. They said their #8cantwait proposals to decrease police violence by 72% have “detracted” from the larger conversation on police brutality. Critics said the group’s proposals were insufficient compared with calls for defunding police departments.

“Fair questions have now been raised about the analysis underlying the #8cantwait initiative,” Campaign Zero co-founder Brittany Packnett Cunningham said Tuesday in a statement posted to Medium announcing her resignation from the group.

Meanwhile, critics have called recent statements by Mr. Goodell and the images of white Americans leading protests to be symptoms of “white guilt,” hollow sentiments that do more to make apologizers feel better about their privilege than to address systemic racism.

“White people are pushing me and others like me aside to alleviate their own guilt and prove that they are different from Derek Chauvin,” author Chad Sanders wrote in a New York Times editorial, referring to the police officer who knelt on George Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes. “Many white people I know are spilling over with guilt and overzealous attempts to offer sympathy.”

Instead, Mr. Sanders called for white friends to fight “anti-blackness.”

Nevertheless, some aren’t apologizing. The Minneapolis police union boss, Bob Kroll, characterized protesters in Minnesota as “terrorists” and didn’t include any mention of sympathy for Floyd’s death in a letter to the federation last week.

“You’ve turned the tide of the largest scale riot that Minneapolis has ever seen,” Mr. Kroll said, amplifying support for officers without addressing criticism of systemic racism within the force.

His strident stance matches that of a man he has appeared with at rallies: Mr. Trump, whose own persona as a pugnacious, never-back-down leader garnered him success in the 2016 election.

Still, the perverse consequences of apologies is that those who apologize — say, then-Sen. Al Franken, who apologized to women for inappropriate touching — often don’t satisfy the apology seekers.

But when interpersonal relationships, not powerful titles or jobs, are what matters, apologies will continue to be the best option for building trust, Ms. Frantz said.

“If your goal is to wield power, then you might not need to apologize,” she said. “But [an apology is needed] if you actually care about being in relationships with others.”

• Christopher Vondracek can be reached at cvondracek@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.