Bill Donner of Seattle makes labels for a living, so he doesn’t toss them out lightly. He takes it to heart when he brands city leaders MIA when protesters took over his neighborhood.

He says he knows dereliction of duty when he sees it, and he has joined a lawsuit to hold Seattle officials responsible for turning the city into a nightmare.

“The mayor and City Council abandoned this neighborhood,” said Mr. Donner, whose custom printing and decals business employs 70 people. “When you have a progressive, socialist government and moderation is out the window, then the government is getting exactly what it deserves.”

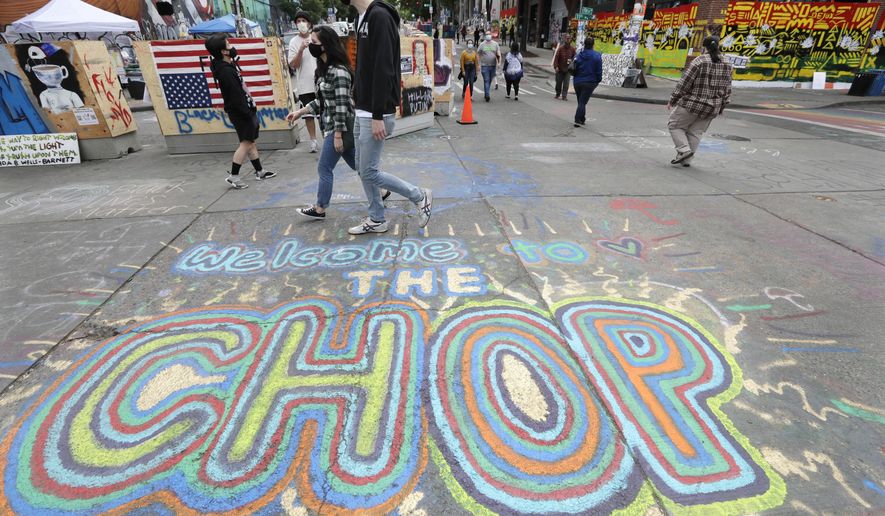

Mr. Donner’s Richmark Label has been a fixture for five decades in Seattle’s Capitol Hill, a neighborhood made legendary or infamous, depending on taste, as the protester-controlled “CHOP” or “CHAZ.”

Before left-wing agitators seized control, Capitol Hill was known for its eclectic architecture and motley collection of residents and workers. It was, in many ways, a modern liberal dream neighborhood with its own Wikipedia entry extolling its “hip bars, eateries and gay clubs, plus laid-back coffee shops and indie stores.”

Richmark Label, which found itself almost dead center in the CHOP, makes intricate, colorful labels for craft beers, gourmet coffee, organic ice cream and the like.

SEE ALSO: Portland protesters using lasers targeted with increased force

It is housed in a 1927 building that was festooned with local artists’ mural work.

“Everybody has been a good neighbor for years. We were one of the centers of Seattle’s gay and Black communities,” said Mr. Donner, 71.

Now, suddenly and unwillingly, he finds himself a plaintiff against his hometown as his placid existence has been shattered.

The urban idyll for Mr. Donner and the 20 other plaintiffs changed June 8 when Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan, a Democrat, chose to abandon the city police department’s East Precinct. Demonstrators stormed the station house like it was a West Coast Bastille.

What began as a protest of the death of George Floyd morphed into something much bigger and, at times, more menacing.

Armed people were seen milling about in the six-block zone. A tent city bloomed in Cal Anderson Park. Barricades once used for municipal events were repositioned in the middle of public streets, barring entry to the self-proclaimed CHOP, or Capitol Hill Occupied Protest, which was later renamed CHAZ, or the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone.

For Mr. Donner, the takeover of his neighborhood in June seemed like a bad dream and sometimes a nightmare.

He and the other plaintiffs accuse the city of deliberately violating their rights and denying them the opportunity to redress their grievances.

“There were people milling up and down the street and the bulk of the protesters were civil,” he said. “But at night it could get worse. It was calm out there a lot of the time, but there was no safety.”

Mr. Donner said he was forced to pass checkpoints to go to work and once drove on the sidewalk to get around one. Some days, employees were too frightened to come to work at the stores that dared to stay open.

When the police-free zone finally came to an end after nearly a month, Cal Anderson Park and its turf playing field, once the pride of the neighborhood, had a slick surface of garbage and feces.

It seemed the only person to profit from it was the Dirty Dog hot dog salesman who would park his cart nightly in the Richmark Label lot.

“He did a bang-up business. Nobody stole any of his stuff,” Mr. Donner said.

Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best rarely minced words when she described CHOP as a lawless menace and an entity that a healthy city should not countenance. Her remarks pepper the lawsuit, which says officers had no chance to provide the services most Americans take for granted each day.

“I don’t blame the police at all,” Mr. Donner said. “But nobody talked to the mayor. Where was the mayor? It seemed it was only when we suggested they go to a council member’s house or the mayor’s house and threatened the lawsuit that anything finally happened.”

The plaintiffs went to City Hall. Instead of finding responsive public officials, they faced indifference. Ms. Durkan and some members of the Seattle City Council, having fended off a slate of candidates backed by Seattle’s rich tech industry, emerged more aggressively left-wing than ever.

“The mayor moves port-a-potties in, and the council people love to give speeches, but they haven’t produced anything,” Mr. Donner said. “They talk a lot and do very little.”

Many legal experts predict the lawsuit will have difficulty succeeding, but the 21 plaintiffs have engaged veteran trial lawyer Angelo Calfo.

Mr. Donner and the plaintiffs have stressed repeatedly that they understand many goals of the CHOP protesters and the broader Black Lives Matter movement, and the lawsuit takes pains in its opening paragraphs to underscore that support.

What’s more, Mr. Donner said, Seattle is not immune to social issues bedeviling other U.S. cities. While shareholders and employees of Microsoft, Amazon, Boeing and other corporate behemoths in Seattle have become rich, the same is not true of many residents.

“We’re home to some of the richest people in the world,” Mr. Donner said. “They made their money here. Many of the people that helped them become so successful can’t even live in the city.”

Living in Seattle, even for those with money, has been complicated and made fragile by the CHOP and continuing protests. On July 19, another wave of unrest roiled Seattle. This time, it began at the police department’s West Precinct and rolled toward Capitol Hill.

On Wednesday night, a group of about 150 people shattered windows, broke into businesses and started fires in the neighborhood, authorities said.

By the time the mayor finally ordered police to retake the CHOP, a dozen cops were injured and protesters inflicted significant damage to government buildings and private businesses.

“Our mural has been completely defaced,” Mr. Donner said sadly. “We’ll repaint. But who’s going to move into this area now? Tenants have asked to get out of their leases, and how long is it going to take to get our neighborhood back?”

• James Varney can be reached at jvarney@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.