The racial justice movement has police departments nationwide desperately seeking training programs to help their officers navigate interactions with minorities, and it has spawned a cottage industry of companies offering training to overcome implicit bias.

The courses can cost as much as $1,000 per officer, which is drawing players into the field that police chiefs say they have never heard of before.

Worries also abound that these fly-by-night startups could do more damage than good. Adopting the wrong techniques could leave departments even more vulnerable to scrutiny and lawsuits.

“Every time a national police story pops up, some group tries to take advantage of it,” said Chief Joseph Lukaszek of Hillsdale, Illinois. “For every 10 emails I get every single day, two are for this kind of crap.”

He said some of the solicitations “are absolute pyramid schemes.”

“It looks good on a piece of paper, but is it effective? And do you want to be the test case?” he said.

Companies flagged by chiefs didn’t respond to inquiries from The Washington Times about their courses and their credentials.

The person who answered the phone at one company said he was only marketing the training and couldn’t vouch for the training. He declined to provide contact information for those who operated the course.

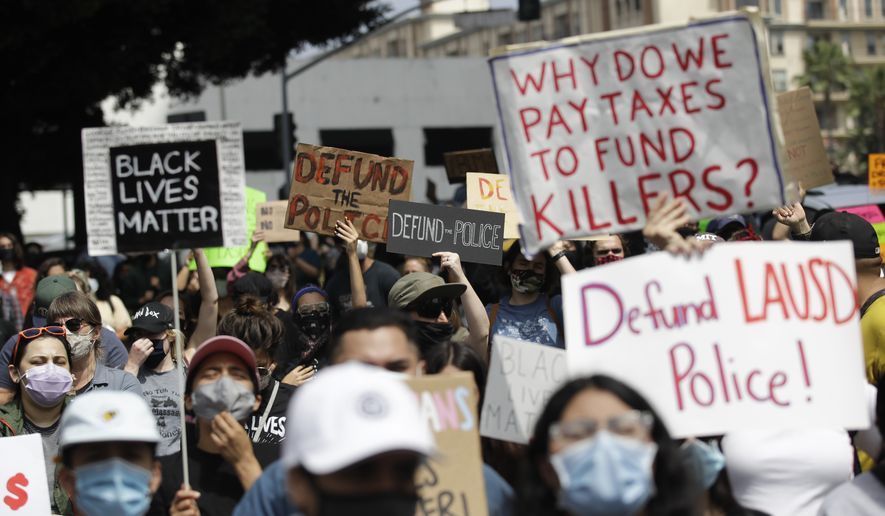

Protesters and politicians are putting pressure on law enforcement to provide training on implicit bias in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death. At the same time, they are calling to slash police budgets, leaving departments with less funds for training.

Texas last month ordered all police officers to attend a course on implicit bias. A similar edict was imposed in Milwaukee, and the City Council in Nashville, Tennessee, is weighing mandatory training for officers.

The New York Police Department recently agreed to a two-year, $4.5 million contract with a private company to provide training.

Proper training can be of great value, police chiefs say, but they warn that increased demand for training and reduced budgets could lead departments to choose training based on cost, not quality. That’s dangerous, they say, because cheap training is likely worthless.

“I think there should be a push to force people to make sure the dollars they spend on training are worthwhile, particularly as we defund and reimagine the police,” said Chief Jeff Kruithoff of Springboro, Ohio, who also is a board member of the FBI National Academy Associates.

“If you can’t afford quality training, you should be pressured to get out of law enforcement because you are exposing the entire occupation,” he said.

Smaller departments are particularly vulnerable because they don’t have the staff to vet the companies. Some departments simply hire the first company that comes along after the mayor or other officials order training.

“Use of force lawsuits always — 100% — go back to the training,” Chief Lukaszek said. “Lawyers want to see the syllabus, the teacher and instructor. You call the company for their expert testimony, and they are nowhere to be found. You are stuck holding the bag with nothing to fall back on.”

Police chiefs say vetting and certification are more important than ever in the current environment.

The Police Executive Research Forum, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the Fraternal Order of Police and the International Association of Directors of Law Enforcement Standards and Training (IADELST) are among those that vet police training.

Peggy Schaefer, who oversees certification for IADELST, has seen an uptick in organizations seeking a stamp of approval. She said some of the groups disappear soon after she explains the standards for certification.

“There are a lot of training programs out there that are a series of power points and slides and a video, and they call that training,” she said.

Yet few who go through the process are rejected.

Since 2015, only 33 of the 216 companies that have applied for an IADELST certification have failed. Ms. Schaefer said she wants applicants to meet the standards because of the extreme need for training.

Police training is definitely a seller’s market, which is enticing entrants.

“Currently, you might have a few companies in the implicit-bias realm, and they cannot service the entire 18,000 departments across the country,” Ms. Schaefer said.

Some training programs, though, resist the demand for certification.

“There is no national standard and group of organizations that thoroughly vet all of the classes out there. And if some group does put a stamp of approval out there, what does that mean? Because who vets their vetting process?” said Jim Glennon of Calibre Press, who has been training on implicit bias since 1995.

Mr. Glennon, who used to teach interview and interrogation, said his courses are more nuanced than others because his degree in psychology helps officers delve into the way the unconscious mind works.

“It is not a racism class; it is an implicit bias class,” he said.

Calibre Press, he said, has taught more than 20,000 officers per year for over 40 years.

“There is a certain complexity because we are all biased. You can tell when your spouse is going to be so touchy about a certain subject,” he said.

The benefits of the training go beyond racial matters and can be useful for officers who have to interact with pedophiles, people who are drunk and others who have acted negatively toward them in the past, he said.

Randy Means of Randy Means & Associates, who has been training law enforcement for 40 years and on implicit bias since the 1990s, said he has not seen the need for certification.

“You could make an argument that I would have been a better businessman if I had got the certification,” Mr. Means said. “I didn’t feel like I needed that. I have had training come in the door because of my merit as opposed to connections and associations with others.”

He works with the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and only recently began promoting his classes widely because of demand.

His courses include content created by Black officers who have been on both sides of the divide between police and Black communities.

“This has become a hugely important issue post-George Floyd,” said Mr. Means, “because now more than ever so many people across society — and not all in the same political camps — say this has got to change.”

• Jeff Mordock can be reached at jmordock@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.