School civics classes teach that the Constitution guarantees the right to remain silent, freedom of speech, equal protection under the law, and a wall of separation between church and state.

Except the founding document never actually talks about a wall.

“It’s something that the courts and anti-religious groups created to keep religion out of our public square,” says John Bursch, senior counsel at Alliance Defending Freedom.

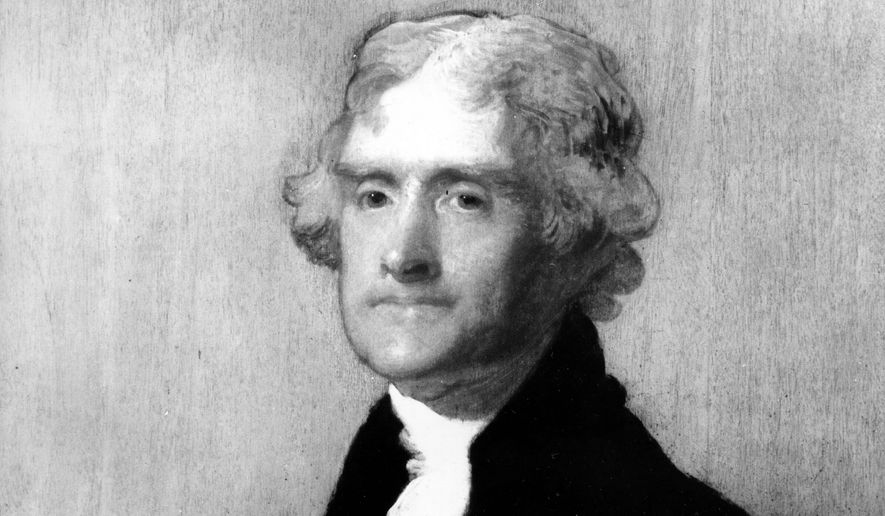

Like so much of founding-era wisdom, the concept of separation of church and state sprung from the mind of Thomas Jefferson — though he was not part of the 1787 Constitutional Convention, nor was he in that first Congress that drew up the amendments that would become the Bill of Rights.

The third of those 12 amendments sent by Congress to the states for ratification included the admonition that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Only 10 of the 12 amendments were ratified at the time — the first two didn’t earn enough states’ approval — which is how the third amendment became the First Amendment in late 1791.

Enter Jefferson a decade later, in early 1802, now in the White House and being battered by his political enemies, the Federalists. Publicly pious and eager to show it, they promoted days of fasting and prayer and wanted Jefferson to follow John Adams’ lead and proclaim them from the newly opened White House.

He fired off a letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut, in which he laid out his vision of “a wall of separation between church and state.”

The Library of Congress in the 1990s decided to try to figure out more about what was behind Jefferson’s letter.

They roped the FBI into helping out, and the bureau used its state-of-the-art lab facilities to recover the rest of Jefferson’s original draft.

The draft reveals that Jefferson originally wrote of a “wall of eternal separation between church and state.” And the draft also reveals that Jefferson had no intention of it being “a statement of fundamental principles; it was meant to be a political manifesto, nothing more,” James Hutson wrote for the Library of Congress.

Indeed, he says, two days after he wrote the letter, he attended a prayer service held in the chambers of the House of Representatives. Jefferson would attend similar services “constantly” throughout his presidency, Mr. Hutson wrote.

Rob Natelson, a leading constitutional scholar who now heads the Independence Institute’s Constitutional Studies Center, said turning to Jefferson for wisdom about the Constitution would be like asking someone on the political fringe today.

“If you want to understand the Constitution, you’re much better off looking at people like James Wilson,” he said.

The letter to the Danbury Baptists was obscure for decades, only gaining new attention when Jefferson’s writings were published in 1853 and reprinted in 1868 and 1871, Mr. Hutson wrote.

But some important people took notice. In 1879, the Supreme Court, in a case dealing with a Mormon who cited his religious duty as a defense against bigamy charges, cited Jefferson’s letter to the Baptists as the guiding light of the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

“Coming as this does from an acknowledged leader of the advocates of the measure, it may be accepted almost as an authoritative declaration of the scope and effect of the amendment thus secured,” wrote Chief Justice Morrison Waite for the unanimous court. “Congress was deprived of all legislative power over mere opinion, but was left free to reach actions which were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order.”

In 1947, the court for the first time would extend that separation to the states, ruling that the “wall must be kept high and impregnable” — yet also ruling that New Jersey could provide busing for Catholic school students and not run afoul.

In the 1980s, then-Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist would complain that the court had bungled things by citing Jefferson as the expert, calling the wall language a “misleading metaphor.”

And the high court has repeatedly struggled to figure out what the wall looks like and when its impregnability is threatened.

Colin McNamara, staff attorney at the American Humanist Association, which lost last year’s battle over a cross memorial in Bladensburg, Maryland, said the courts are becoming “more hostile” to Jefferson’s vision of separation of church and state.

He disputed those who see the push for separation as an attack on those of faith.

“There is no mass movement out there to undermine traditional American values,” he said.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

• Alex Swoyer can be reached at aswoyer@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.