OPINION:

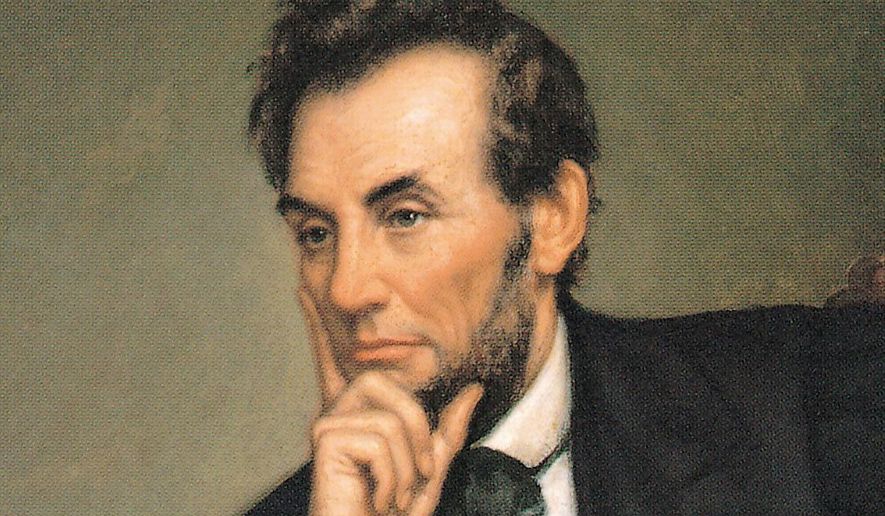

Feb. 12 is the birthday of Abraham Lincoln, a man “both steel and velvet,” in the words of his biographer, Carl Sandburg.

When we think of Lincoln, we usually think of his velvet side. We think of the Lincoln who ordered the band to play “Dixie” when exuberant crowds gathered outside the White House to celebrate Robert E. Lee’s surrender at the end of the Civil War. We think of the Lincoln who closed his second inaugural address by saying, “With malice toward none, with charity for all … .” We think of the Lincoln who made a point of very publicly asking black abolitionist Frederick Douglass his opinion of the inaugural address, “as there is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours.” We think especially of the numerous cases where Lincoln exercised his power to pardon. During his presidency, he personally reviewed more than 1,600 cases of military justice, generously pardoning soldiers condemned to death for desertion or sleeping on duty if he could find the slightest mitigating circumstance.

Yet, if Lincoln had not had as much steel as velvet in his character, he could never have made the tough decisions necessary to bring a bloody civil war to a victorious conclusion. Historian Eliot Cohen shows us a little-known example of Lincoln’s steely side in his book, “Supreme Command: Soldiers, Statesmen, and Leadership in Wartime.”

According to Mr. Cohen, Lincoln feared — with good reason — that there were officers in the Union Army who opposed his policies and favored a compromise peace with the South. Lincoln recognized the danger of covert opposition within Union ranks and dealt with it accordingly.

One instance involved a certain Maj. John J. Key, the brother of one of Gen. McClellan’s closest aides. Just after the Union victory at Antietam in September of 1862, a fellow officer asked Key why McClellan had not pursued and destroyed Lee’s retreating army. Key replied: “That is not the game. The object is that neither army shall get much advantage of the other; that both shall be kept in the field till they are exhausted, when we will make a compromise peace and save slavery.”

When Lincoln heard of Key’s remarks, he summoned him to the White House and demanded to know if he had actually said the words that had been imputed to him. When Key could not deny the charge, Lincoln immediately dismissed him from the service, saying that it was “wholly inadmissible” for anyone expressing such views to hold a commission in the U.S. Army.

Key was crushed. In spite of his careless talk, he was pro-Union. In an effort to obtain reinstatement, he collected a sheaf of letters from fellow officers attesting to his loyalty and asked his former commander, Gen. Henry Halleck, to submit them to the president.

Lincoln had every reason to believe that Key’s contrition was sincere. The testimonials aside, Key had just made the greatest sacrifice to the Union cause that a father could make: His 18-year-old son, a captain of the Ohio Volunteers, had died of wounds he received in battle just two weeks before Key’s petition for reinstatement reached the president’s desk.

Lincoln was moved, but he stood his ground. He wrote the grieving, cashiered major a letter in which he expressed his personal sympathy for the death of Key’s son. But in the same letter he went on to say that there could be no question of restoring Key to the ranks.

Lincoln wrote:

“I did not charge, or intend to charge you with disloyalty. I had been brought to fear that there was a class of officers in the army, not very inconsiderable in numbers, who were playing a game to not beat the enemy when they could, on some peculiar notion as to the proper way of saving the Union; and when you were proved to me, in your own presence, to have avowed yourself in favor of that “game,” and did not attempt to controvert the proof, I dismissed you as an example and a warning to that supposed class. I bear you no ill will; and I regret that I could not have set the example without wounding you personally. But can I now, in view of the public interest, restore you to the service, by which the army would understand that I indorse and approve that game myself? If there was any doubt of your having made the avowal, the case would be different …

“I am really sorry for the pain the case gives you, but I do not see how, consistently with duty, I can change it.”

Mr. Cohen says that Lincoln reviewed Key’s appeal a third and final time, two days after Christmas of that same year, with the same result.

Abraham Lincoln is arguably the greatest man that this country ever produced. He is also one of the most complex; a man “both steel and velvet.” We like to remember Lincoln’s softer side, but if he hadn’t had the steel as well, we might not be one nation today.

• Thomas C. Stewart is a former Naval Aviation attack commander and a retired New York investment banker.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.