OPINION:

Most folks think of the AARP as a membership organization that gives older Americans discounts on magazine subscriptions and cellphone plans. In fact, those business lines are secondary to AARP’s real source of income, a lucrative partnership with United Healthcare.

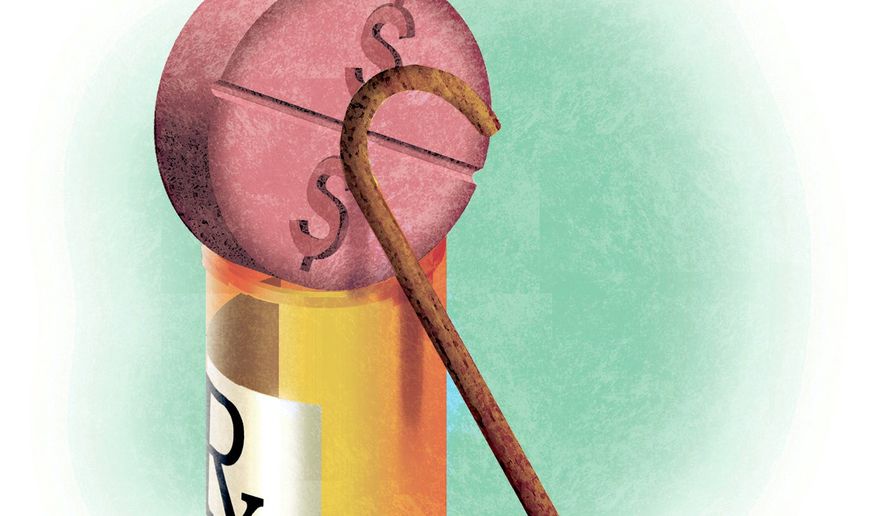

AARP partners with United Healthcare to offer health insurance plans to its membership. On its face, there’s nothing inappropriate about this type of affinity branding; the problem is that United Healthcare (and, frankly, other insurance companies) have made some decisions at the expense of seniors and the Medicare program, which should run counter to what a seniors-focused advocacy organization endorses. Recent actions by United Healthcare to limit seniors’ access to less expensive versions of Medicare drugs calls into question whether the AARP is looking out for older Americans or its own bottom line.

During the past three years, President Trump has maintained a laser focus on drug prices, causing pharmaceutical companies to respond in a variety of ways, including reducing or, in some instances, halting altogether annual price increases, pledging responsible pricing for new medications and reducing the price of medicines in certain instances.

For example, last year Eli Lilly launched a half-price version of its insulin drug, Humalog, to address affordability barriers for diabetic patients. Gilead created a subsidiary company in order to offer its two revolutionary hepatitis C products, Harvoni and Epclusa, as “authorized generics” at prices more than 70 percent lower than the identical brand version. In 2018, two companies competing in the cardiovascular space, Sanofi and Amgen, each introduced less costly versions of their cholesterol medications for patients who are unresponsive to statins — at 60 percent below the original price. These are all big wins for Mr. Trump’s jawboning campaign.

But the system is not working: These less expensive versions of innovative drugs are not available to many seniors because of how insurance companies and their negotiators (known as “pharmacy benefit managers” or PBMs) design drug coverage via formularies, particularly in Medicare. A perfect case study is cardiovascular disease, the No. 1 cause of death in the United States: For the past 14 months, in many instances, United Healthcare formulary design kept patients on the more expensive versions of the Sanofi and Amgen cholesterol medicines which came coupled with a high out-of-pocket co-insurance for the patient. Further, CVS (which is merging with insurance company Aetna) admitted to creating barriers for patients by requiring doctors to provide a “documented clinical reason” for prescribing the identical, cheaper version of the same medicine. Today in Medicare, CVS continues to block affordable access to the lower cost versions by not covering these medicines anywhere on their national formulary, effectively dissuading a patient at high risk for a heart attack or stroke from purchasing the medicine prescribed by his/her cardiologist.

Why would insurance companies and PBMs want to keep paying for the more expensive version of an identical drug? The answer lies in the backward way drugs are priced in America. Drug manufacturers set the “list price” of a drug the same way a car dealership lists the price of cars or colleges list the price of tuition. What’s actually paid by an insurer in the final transaction is usually steeply discounted from the starting price by the drug company “rebating” a portion — 40 percent on average, oftentimes more — to the PBM/insurance company (which then pocket it). That negotiation should result in reduced out-of-pocket drug costs for seniors. The problem is that this model results in perverse incentives.

Medicines have high “list prices” because the drug company knows that it will need to provide significant discounts/rebates in order to be listed on a health plan’s formulary. Positive formulary placement = patient access to a medicine. Insurance companies and PBMs like the higher list prices because they profit from both the steep, negotiated rebates and the higher co-insurance the patient pays to the plan. In Medicare, once a patient barrels through the initial drug coverage phase, the federal government picks up 80 percent of a senior’s drug costs, reducing the insurer’s liability. In the end, it’s patients who suffer at the pharmacy counter and in the long run.

All of that takes us back to AARP/United Healthcare and the biggest pharmacy in the country, CVS. Why are some of the nation’s largest health care organizations keeping drug prices high for seniors? Whose side is the AARP on, anyway? The facts draw their own conclusion.

• James L. Martin is founder/chairman and Saul Anuzis is president of 60 Plus Association.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.