MONROE, La. (AP) - America’s understanding of racism and the part it played in our country’s history are undergoing a sea change.

But have the ways that our children are learning about slavery, the Civil War, Jim Crow laws that legalized racial segregation and the civil rights movement adapted to reflect that growth? Are Louisiana’s students getting a whitewashed version of history, or are they given facts that they can use to form their own understanding?

“I would especially say, given our times today and given the region we live in, that there’s a woeful almost ignoring of Reconstruction and Jim Crow and the civil rights era,” said David M. Anderson, the graduate coordinator for the School of History and Social Science at Louisiana Tech University.

“So when I’m teaching them at my level, it is relatively new to them, especially when I go through post-Reconstruction and through Jim Crow or discuss something like lynching,” Anderson said. “I would say, no, 99% of my students have no idea the extent of lynching in the South, say from the 1880s to the 1920s. It is something brand new to them.”

HOW PREPARED ARE STUDENTS?

How students learn about our nation’s history shapes how they look at current events and race relations today and in the future, an impact that extends beyond the classroom.

“Schools play a powerful role in helping students deconstruct and construct, building fluency and empowerment in the social and political interactions that play out in their lives,” wrote Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education member Kira Orange Jones in an Aug. 6 column for PublicSchoolAdvocates.org.

“The social studies are there for a reason,” said Toby Daspit, interim head of the University of Louisiana Lafayette Department of Educational Curriculum and Instruction. “We want civically minded, engaged individuals. It is essential to maintaining a democracy. Our democracy is very fragile right now, more so than ever.”

There seems to be a consensus in Louisiana education that students are taught social studies differently today, perhaps more inclusively and straightforwardly, than they once were. But many argue it’s not enough.

“I think it moved a tick over, but it’s nowhere near where it needs to be,” said Tori Flint, assistant professor of literacy at UL Lafayette.

Fellow UL Lafayette assistant professor Natalie Keefer teaches social studies methods classes for college students training to become history teachers.

“I’ve had students come up to me after class and they’ll say to me, ‘Wow, we didn’t get this; how come we never knew about this when we were in high school?’” Keefer said.

Flint and Keefer dug into what’s being taught in the classroom over the past year as they co-authored the book “Critical Perspectives on Teaching in the Southern United States.”

“The South is just such a unique kind of place with its own place and histories and contexts, and teaching in the South is obviously influenced by those,” Flint said. “We wanted to just gather a variety of perspectives on what it means to be teaching in that kind of context.”

WHY IS DIVERSITY IMPORTANT?

Monroe City School Board member and teacher Rick Saulsberry said the history of Black people in America starts with slavery.

White children learn about European countries and kings and queens, he said. Black children don’t get that breadth of history about Africa or African-American contributions to society.

Saulsberry taught social studies in Louisiana for a decade to students in seventh through 12th grades. For the past four years, he’s taught special education.

Preston Castille, a member of the Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, wants to “ensure these parts of our shared history are taught to all of our students.”

He sees an opportunity to do that through improving standards and materials that better address these topics.

“Other countries that have a similarly dark past, such as Germany with respect to its treatment of the Jews, have taken a much more proactive approach to educating its citizens and encouraging not only an understanding of that country’s history, but also its deep modern-day commitment to acknowledge and address the mistakes of the past,” Castille said.

It’s not just about whether these topics and demographics are included, but also how they are represented, Flint and Keefer said.

“It’s just so normalized that everything is focused on white and male, generally, so people of color and women are just left out,” Flint said. “It’s just so normalized in America that we’re like OK, that’s our history.”

Keefer and her colleagues are careful about getting their college students to think about creating curriculum that takes a broader look at Black history beyond slavery.

“If all Black students are hearing about their history is enslavement, enslavement, enslavement, then they’re not hearing about the civil rights movement,” Keefer said. “They’re not hearing about the education that started to blossom and bloom in Louisiana during Reconstruction, and they’re not hearing about other things.”

But everyone doesn’t learn that Louisiana had the first Black governor in the U.S. during Reconstruction, Saulsberry said.

P.B.S. Pinchback served as interim governor from Dec. 9, 1872 to Jan. 13, 1873.

In 1868, Pierre Caliste Landry was elected mayor in Donaldsonville, making him the first Black mayor in America.

If any of that gets covered, Saulsberry said, it’s in a paragraph.

The impact of under-representation extends beyond school and into society at large, Anderson said.

“Historians have a phrase that all history is present history,” Anderson said. “What happened in the past doesn’t change, but how we think of those events and apply them to the past does.

“We’re in the midst of social justice movements, and the leaders of this find those areas to be revealing about the present. We don’t want to keep history quaint and nice just serving a mere purpose as a curiosity. ‘Oh, look how different people were back then.’ We want to utilize it for the present,” he said.

That’s what Yardley Hill, 25, a college senior who is student teaching civics in Lafayette Parish this year, aims to address.

“I just want to prepare my students for life after high school,” Hill said. “I want to prepare students to be able to think about what they hear or think or see and connect it to the past and find what’s relevant, and not base their opinion on emotion or limited knowledge from Instagram videos or tweets.”

HOW ARE CHILDREN LEARNING?

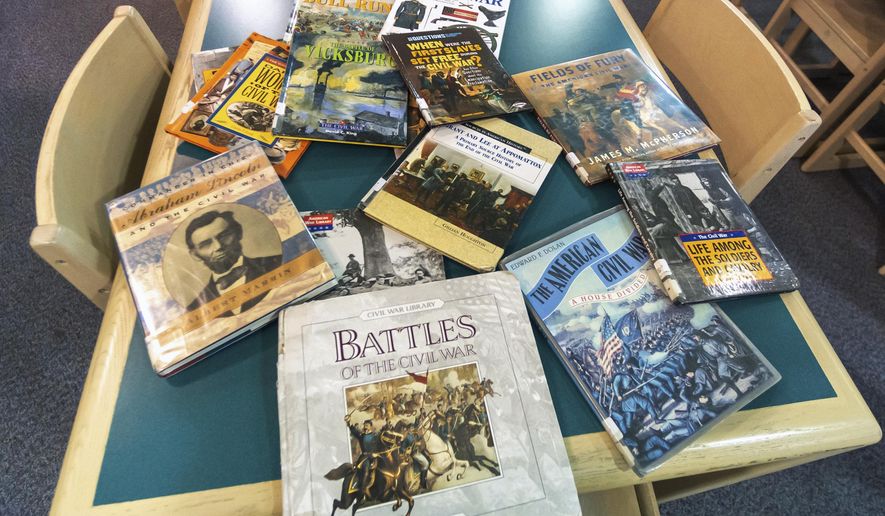

Ashley Ellis, a member of the Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education and assistant principal at Neville High School in Monroe, said when the Louisiana State Standards were developed and social studies committees collaborated there was a huge shift from textbooks and third-party sources and information.

Instead, she said, students are looking at materials such as the U.S. Constitution directly, learning how to analyze the documents and put them in historical context.

School districts can choose any curriculum they want, Ellis said, but guidebooks provided online by the state are designed to connect past and present using key themes and teach the students how to make informed opinions.

”(The guidebooks) are pretty scripted and pretty available for anybody to read and see, ‘What are we teaching for Reconstruction?’” she said. “Obviously, just like any course, it depends on whether the teachers follow the guidebooks closely or supplement with their own thoughts or grabbing something from somewhere else.”

At the end of each unit, students have to write an essay using primary source documents to guide their writing and answer a claim or question posed as part of the curriculum.

While some are still concerned about whitewashed studies, current textbooks include phrases such as “shot by a white racist,” “white flight” and “de facto segregation to which government turned a blind eye.”

Although once focused mostly on Martin Luther King Jr. alone, more minorities and key figures of the civil rights movement - like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael - are included, as are more recent incidents such as police brutality against Rodney King in 1992 and the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., in 2014.

The seventh-grade textbook unit on slavery doesn’t hide the role slavery played in the Civil War, but it speaks about it in an impartial way - like the South’s “fight to preserve its way of life” - which leads some educators to argue materials are oversimplified.

WHAT HURDLES DO TEACHERS FACE?

Difficulties in covering all issues with depth include time constraints, trying to prepare students best for end-of-year tests and concern about tackling controversial topics.

“Pacing is a challenge,” Daspit said. “So much has to be covered. The No. 1 complaint I hear from students who become teachers is, ‘We don’t have the time to do it.’ The question teachers have to ask is, ‘What knowledge is of most worth?’ You can’t cover everything.”

But it seems necessary for context. It’s impossible, Anderson said, to understand Jim Crow without understanding slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction.

Anderson said students, especially from white-majority schools, say they don’t engage in racial topics because it’s too controversial. Teachers also face this fear, Daspit said, describing it as defensive teaching.

“And my response to that, and as a citizen, is I think that should be something they should engage with head-on,” Anderson said. “And if we’re not doing it in public schools, where else are we going to do it?”

___

The Louisiana Department of Education declined an interview for this piece, noting the Legislature’s second extraordinary session. As of Oct. 19, 34 education-related bills had been suggested.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.