The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated a “cold war” between communist China and the United States, with Beijing scrambling at levels previously unseen to try to undermine America’s status as the world’s leading superpower.

Although the recent emergence of coronavirus vaccines suggests the pandemic’s end may be in sight, foreign policy analysts generally agree that the expanding geopolitical battle between Washington and Beijing will only intensify in the post-COVID-19 era.

“We now have underway a full-blown cold war between the U.S. and China,” said Clifford D. May, president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington think tank known for its hawkish foreign policy positions.

“This war actually started years ago,” Mr. May said in an interview. “But America’s elites, Republican and Democrat, have been in denial about it considering how much Wall Street is invested in China and how much U.S. consumers have been accustomed to cheap goods from China often made from exploited, if not slave, labor.”

Although he credited the Trump administration with engineering a clear-eyed shift in U.S. policy toward China even before COVID-19 hit, Mr. May said the U.S. establishment has been dangerously slow to let go of false and long-held beliefs that China will liberalize its political system and moderate its behavior on the world stage as its wealth grew through ties to America and the U.S.-backed global economic order.

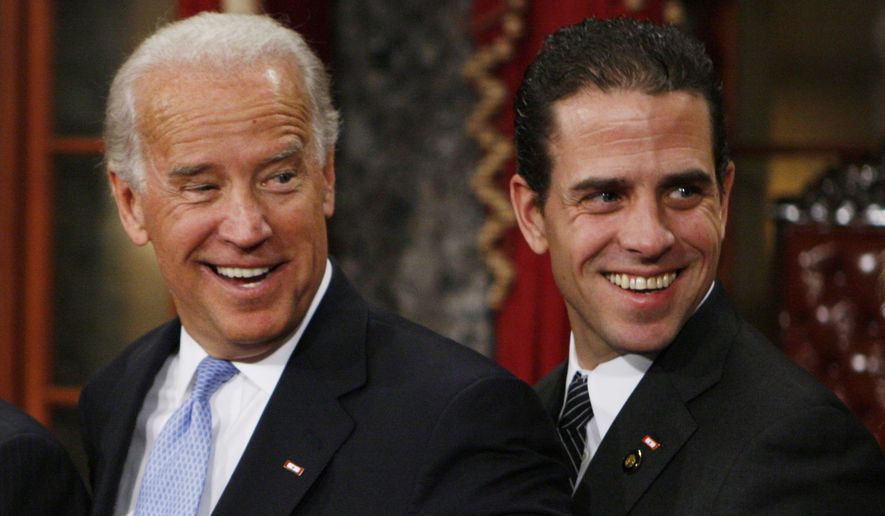

China hawks say that has not happened, and President-elect Joseph R. Biden faces difficult questions on whether to embrace President Trump’s hard-edged approach or seek a reversal toward the moderate and much softer posture the U.S. embraced when he was vice president.

Republicans view Mr. Biden with skepticism because of his son Hunter’s checkered history of business dealings in Beijing.

The broader uncertainty over China policy stands to shape the next administration’s approach to other global issues, including those involving North Korea and Iran. As a neighbor and ally of North Korea and a permanent, veto-wielding member of the U.N. Security Council, China already has influence in both of those arenas and could increase that influence given likely disruptions in the post-COVID-19 era.

China also poses major questions about how its power moves will influence the behavior of other U.S. adversaries such as Russia, which the Trump administration quietly sought to peel away from China. The administration hoped to create a strategic alignment of allies including India, Australia and Japan to present a united front in countering China.

Mr. Biden will arrive at the White House during Beijing’s accelerating push to portray itself to the world as a more organized and reliable partner than the U.S., especially to weaker nations facing the hardship of a pandemic-driven global economic downturn.

Beijing is already billing itself as a better global citizen than Washington. It touts its dedication to multilateral organizations such as the World Health Organization, the Paris climate accord and the World Trade Organization that Mr. Trump shunned while appealing for Mr. Biden to shift away from his predecessor’s “America First” policies.

The Trump administration “ignores the vast common interests and room for cooperation between the two countries and insists that China is a main threat,” Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in a speech Friday to the New York-based Asia Society.

“This is like misaligning the buttons on clothing,” Mr. Wang said. “They get things wrong at the very beginning.”

By contrast, the Trump administration’s leading voices on China, led by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, readily embrace the cold war idea and warn that Beijing could be an even more formidable adversary than the Soviet Union, which operated in a political and economic sphere largely separated from the West.

“What’s happening now isn’t Cold War 2.0. The challenge of resisting the [Chinese Communist Party] threat is in some ways worse,” Mr. Pompeo said in a September speech in the Czech Republic. China “is already enmeshed in our economies, in our politics, in our societies in ways the Soviet Union never was.”

Although the novel coronavirus originated in China, Chinese government officials have suggested that the U.S. may have been responsible for the outbreak and argued that China’s system has far outperformed the U.S. in containing COVID-19 and limiting its economic impacts.

China, with its military growing stronger by the year, is also engaged in increased regional muscle-flexing, apparently to test U.S. resolve should a clash break out over flash points such as Hong Kong, Taiwan or control of the South China Sea.

The Chinese military has “stepped up the frequency” of activities around Taiwan as well as near the many disputed reefs and islands of the South China Sea, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

An examination by the initiative found a roughly 50% increase in Chinese military activities in the Indo-Pacific reported by Chinese state-controlled media over the past year. The study cited a similar, albeit less dramatic, increase by U.S. forces in the region.

U.S. officials predict Beijing will be emboldened to increase its military moves as it prepares to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party in July.

High stakes for China

Not everyone is convinced that the fallout from the pandemic will aid China’s emergence.

“The jury is still out as to whether COVID-19 accelerates the geopolitical transition which has been underway before,” said former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, who heads the Asia Society Policy Institute.

“The variable here is U.S. policy and strategy and … whether [that] policy and strategy is sustained beyond the four-year point in terms of a long-term return to American regional and global leadership role,” Mr. Rudd told the annual GZERO Summit hosted this month by the Eurasia Group, a New York-based consulting firm.

He suggested that the Trump administration, despite its confrontational approach to Beijing, ultimately weakened America’s geopolitical standing by going it alone on China rather than pursuing a more cohesive strategy with regional allies. Many on Mr. Biden’s national security team strongly agreed with the criticism.

“The bottom line is the ball is very much now in America’s court about what it wishes to do in the region and the world,” Mr. Rudd said at the summit, which was held virtually under the title “Geopolitics in a Post-Pandemic World.”

The Trump administration’s China hawks warn that the ruling Communist Party’s ambitions are global. They say Beijing is ready to exploit the pandemic-induced global economic crisis to expand its ambitious “Belt and Road” campaign through loans to a growing number of nations in need.

China’s gross domestic product, at an estimated $13.4 trillion, is just two-thirds that of the United States. But its position as a rising powerhouse has been increasingly harder to deny since 2013, when President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road program.

The campaign has since grown into a vast web of deals, contracts, grants and loans. Beijing has doled out well over $100 billion in loans to more than 100 countries to finance roads, bridges, ports and rail lines.

U.S. officials accuse China of engaging in predatory lending by offering loans it knows nations will have trouble repaying, only to offer relief later in exchange for control over coveted natural resources.

Beijing sharply denies such accusations, but China has emerged over the past decade as a go-to source of loans for cash-strapped countries in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Africa, Latin America and parts of Europe. It has become an alternative capital source to the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, the Washington-based pillars of the liberal international economic order that the U.S. has fostered since shortly after World War II.

Criticized early in the COVID-19 crisis for failing to offer concessions to its strapped borrowers, China now seeks to portray itself as benevolently delivering generous debt relief to countries in need.

Finance Minister Liu Kun said last month that Beijing had extended debt relief worth some $2.1 billion to developing countries, but that figure is tiny compared with the mountains of debt that developing countries owe China.

A World Bank study found that the world’s poorest countries owe Beijing more than $112 billion through the Belt and Road program, raising questions of whether China overextended itself as markets and national economies struggle to recover.

Mr. Rudd said China’s reputation already has been damaged by its handling of the coronavirus in the earliest days of the crisis and by what many saw as Beijing’s hubris in trying to exploit its position as the world’s leading supplier of protective medical equipment.

“China,” the former Australian prime minister said, “took a big reputational hit because the virus came from Wuhan.”

“China’s attempt to use the distribution of PPE around Asia and the rest of the world as a tool of diplomacy effectively backfired,” he said, “because China insisted on statements of loyalty to the imperial throne as a precondition for the delivery of PPE. This was received negatively around the world.”

China’s nationalistic state-controlled media even raised the specter of using Beijing’s control over global pharmaceutical supply chains as leverage to block critical components for dependent U.S. drug companies and send America into a COVID-19 “hell.”

The Trump administration and lawmakers from both parties responded by calling for a revamping of domestic U.S. drug manufacturing operations that had been outsourced to China and a handful of other nations. That’s another big question awaiting Mr. Biden as he weighs what it takes to wage a Cold War with China.

Waiting on Washington

Former Japanese Defense Minister Taro Kono, who also spoke at the GZERO Summit, said U.S. allies in Asia are on edge as they await how Mr. Biden approaches the post-Trump and post-COVID-19 geopolitical landscape.

“We need to be very carefully monitoring the United States’ intentions, if the U.S. is again trying to take leadership in building a coalition among the like-minded countries … to sustain democracy, a coalition to protect global rule and trying to protect the liberal international order that has brought about this economic prosperity after World War II,” said Mr. Taro, now minister for administrative and regulatory reform for Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga.

“Is the United States trying to re-create [the] global trade regime? Is the U.S. coming back to the WTO? Is the U.S. joining [pan-Asian Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal]? Hopefully,” Mr. Taro said.

Japan has proceeded with the Pacific Rim trade deal in absence of U.S. support over the past four years. While trade watchers try to figure out whether Mr. Biden will seek to join the Asian trade deal Mr. Trump shunned, some analysts are skeptical that the incoming president understands how dramatically the regional dynamics have changed since he was vice president just four years ago.

“I’m not yet convinced by any means that Biden himself recognizes that it’s a cold war,” Mr. May said.

Mr. May said a key wild card will be how Hunter Biden’s legal problems connected to China affect his father’s ability to alter policy with Beijing. Hunter Biden recently acknowledged that his taxes were under investigation in connection with a former Chinese tycoon now believed to be in jail facing corruption charges.

Mr. Biden has strongly defended his son, but the potentially distracting investigation is poised to proceed at least through the early months of his presidency.

“Joe Biden saw no reason why his son shouldn’t be involved with business with China,” said Mr. May, who writes a regular opinion column for The Washington Times. “Whether he recognizes now that China is a dangerous adversary, we don’t know. Whether he will take a tough policy toward China, we also don’t know.”

Mr. Rudd, meanwhile, suggested the coming four years could bring as much of a geopolitical shift as the past four. The world, he said, should not take lightly the potential for a massive policy shift by the incoming U.S. administration.

“There is a grave danger that people underestimate the capability and capacity of President-elect Biden and the team that he has assembled,” Mr. Rudd said. “This will be as formidable a foreign policy and national security team as was assembled by President Truman after the war, and the Truman administration was much underestimated by the rest of the world.”

• Guy Taylor can be reached at gtaylor@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.