Last month’s election turns out to have been the pre-season.

The real election for president is set for Monday, when groups large and small will gather in state capitals across the country and cast their votes as part of the Electoral College, effectively appointing the next chief executive.

The outcome is not in doubt.

According to the results certified in each state, Democrat Joseph R. Biden won 25 states and the District of Columbia and earned 306 electoral votes. President Trump won 25 states, too, but his are more sparsely populated and earned just 232 electoral votes.

The electors themselves were chosen by the parties earlier in the year, in many cases well before Democrats even knew Mr. Biden and his running mate, Kamala D. Harris, would be their nominees.

The system of electors was created by the Constitution’s Article II and solidified in the 12th and 23rd Amendments — though the term Electoral College doesn’t actually appear in the founding document.

Using electors was a compromise between selecting the president by direct popular election, by a vote of state legislatures, or by Congress. As the founders envisioned it, the average voter might not know enough to make an informed decision about national candidates, but he could select local leaders who would be capable.

Thus when voters went to the polls last month, they were actually casting ballots for a slate of electors.

Since Mr. Biden won Virginia, his electors will be the ones voting for president in that state on Monday. Mr. Trump, meanwhile, won North Carolina, so his electors will be the ones voting there.

“It is a very convoluted process that has evolved over time and is something quite different from what the Founders envisioned,” said Rebecca Green, a professor and co-director of the Election Law Program at William & Mary Law School. “When you look at the certification of the vote, the safe harbor, and the Electoral College, these are all just one more step by which the results become more and more finalized.”

Electors cannot be federal elected officials or anyone holding “an office of trust or profit under the United States,” but can be most anyone else the party chooses. The Congressional Research Service said they turn out to be “a mixture of state and local elected officials, party activists, celebrities and ordinary citizens.”

“With the electors you’ll see a lot of variation,” said Louis Gurvich, chairman of the Louisiana GOP, which picked its electors by caucus in February. “It’s not an election, but you can put it around, quietly, that you’d be interested in being an elector. It’s something you can put on your political resume.”

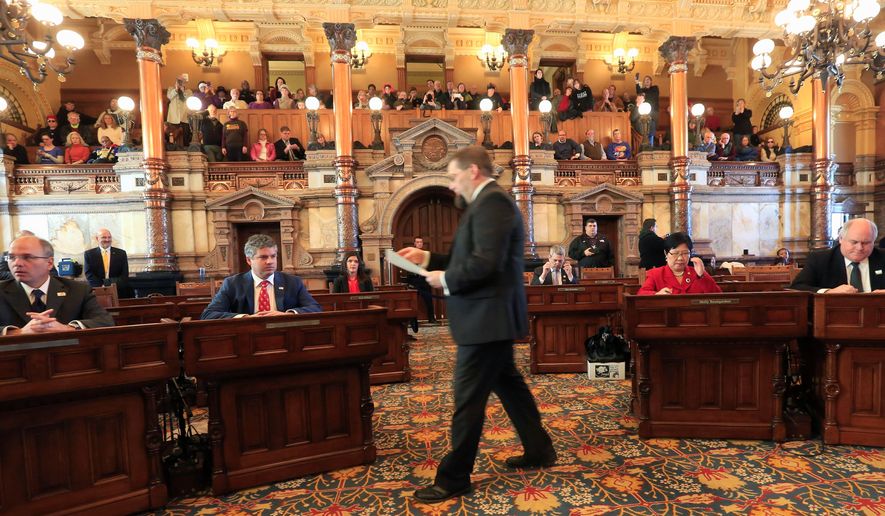

Generally, the electors gather in their state capitols and hold two votes: one for president, another for vice president. The only change that COVID appears to have made is moving the votes to a bigger room.

Every state has a winner-take-all approach to electors, save for Maine and Nebraska, which dole out two electors to the statewide winner, but then award the other electors — two in the case of Maine, three in Nebraska — based on the victor in each congressional district.

In this year, as has happened more often in recent years, both of those states will split their electoral votes, with Mr. Trump winning one of Maine’s four votes and Mr. Biden collecting one of Nebraska’s five votes.

Nebraska electors will first meet in the governor’s office and then, at 2:10 p.m. Central time, move to a larger room necessitated by COVID and hold their vote, the secretary of state’s office said.

“I think there’s a lot of people who are interested this year,” spokeswoman Cindi Allen said. “It’s pretty straightforward, but there seems to be a little more moment to it this time, more attention is being paid.”

The electoral college votes will be opened and read aloud at a joint session of Congress on Jan. 6.

The Trump campaign this week shrugged off the looming Electoral College vote, vowing to press on with its court challenges.

“The only fixed day in the U.S. Constitution is the inauguration of the president on Jan. 20 at noon,” said Rudolph W. Giuliani and Jenna Ellis, the lawyers leading Mr. Trump’s challenges.

Under the Constitution, there is no rule binding electors to vote for the candidate they were attached to on the ballot, and indeed “faithless electors” sometimes defy their voters’ wishes.

In 2016, one elector in Hawaii and four in Washington state, won by Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, cast votes for someone else, and two electors in Texas, won by Mr. Trump, cast deviant votes. That left the final official tally at 304-227.

There’s been little talk of faithless electors this year.

Most state laws contain language that electors “shall” cast their ballots for their party’s candidate who won the state and the Supreme Court this year unanimously upheld state laws punishing “faithless electors — but many states don’t have clear punishments for the occasional elector who votes differently.

“I think a faithless elector would most likely be escorted from the room and another elector would then be appointed,” Ms. Allen said.

• James Varney can be reached at jvarney@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.