OPINION:

The coronavirus has taken the public out of public transportation. At its height, the pandemic turned crowded commuter trains traversing urban centers into giant, virology test tubes on wheels. Once the pestilence has subsided, there is no guarantee that Americans will readily put aside their infection fears and answer the conductor’s call of “all aboard.” That means major upgrades for the nation’s railways, in accordance with Joe Biden’s dream of a “second great railroad revolution,” may wind up sidetracked.

Prior to 2020, only purveyors of dystopia could have imagined the disruption to everyday life wrought by the invisible plague. In populated metropolises like New York City, mass transit trains kept running, but less frequently, in accordance with lockdown mandates. Packing remaining commuters into fewer vehicles precluded social distancing and a U.S. record 23,000 New Yorkers died, including more than 130 mass transit employees.

Although daily deaths in New York, thankfully, have fallen to single digits, rail ridership shows no signs of recovery. For the week ending Sunday, ridership on both the city subway system and the Long Island Railroad was down 76% from the same week in 2019, according to Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA) data. Manhattan bridge and tunnel traffic were only off 14%, though, an obvious indication that commuters feel safer from germs riding solo in their own autos.

Beyond intra-city commuting, the number of passengers riding long-distance along Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor fell by 95% during the height of the pandemic and remains 90% below normal. With Amtrak ridership across the country down 70%, the federally funded rail service has announced the termination of service to hundreds of stations and plans to lay off 20% of its work force.

In March, Congress approved $25 billion in bailout funds for public transit systems like the MTA and Amtrak, and collectively they are seeking at least an additional $32 billion to make up for lost revenue. The multibillion-dollar question is whether in the post-pandemic world those missing fares will pour back into transportation industry coffers, justifying additional taxpayer assistance. It doesn’t look promising.

Prior to COVID-19, about 7% of U.S. employees worked from home, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The proportion has skyrocketed to 62% during the pestilence, according to a Gallup Poll, and 37% say they prefer to continue working remotely indefinitely.

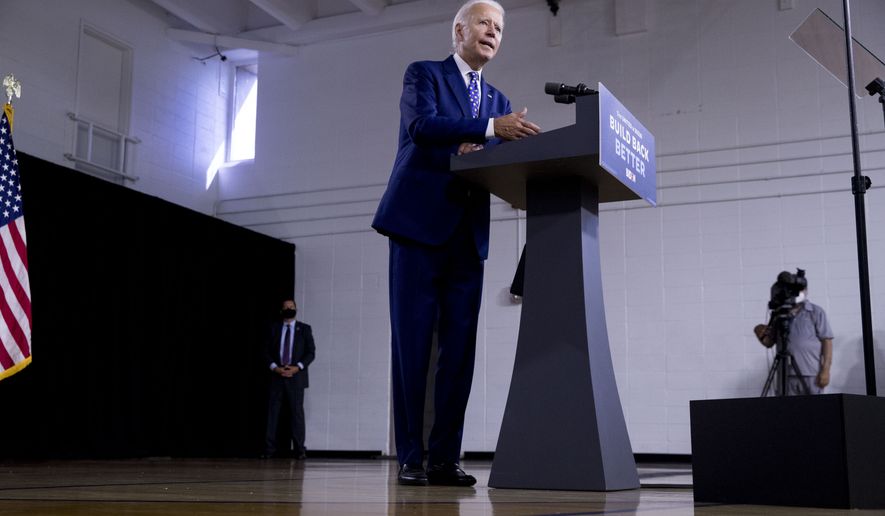

“Amtrak Joe” Biden, the presidential candidate famous for riding the rails regularly between his Delaware home and Washington, D.C., should take notice of the workplace about-face. Plans for major upgrades to the nation’s railways, were he to win the presidency in November, may not make as much sense as they did before Americans learned the value of home-based safety and efficiency.

For starters, the Biden rail platform includes “putting the Northeast Corridor on higher speeds and shrinking the travel time from D.C. to New York by half.” Additionally, the Northeast Corridor would be extended into the Southeast, and then Mr. Biden would construct a high-speed rail system across the middle of the nation to connect the two coasts. “Overall,” reads the plan, “Biden’s rail revolution will reduce pollution, connect workers to good jobs, slash commute times, and spur investment in communities that will now be better linked to major metropolitan areas.”

Citizens have been down that track before. A recent study by the Cato Institute’s Randal O’Toole examined the outcomes of an $11.5 billion expenditure the Obama-Biden administration made in rail improvements in 2009-10. He found $4 billion in federal funds went to California’s high-speed rail, meant to transport passengers between Los Angeles and San Francisco in less than three hours. A tripling of the project’s price tag to nearly $100 billion has left construction unfinished and, 10 years later, Californians are still riding Amtrak trains that strain to average 39 mph.

Of the 10 Obama-Biden high-speed rail projects funded, four resulted in no increase in train speed, three managed to raise the speed slightly (the highest boost was 4.3 mph) and three actually ended up with slower trains.

The coronavirus has altered the way Americans handle their commute and conduct their commerce. Time will tell whether the transformation is temporary or permanent. A Biden “rail revolution” designed for the pre-pandemic era may no longer be the ticket for progress.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.