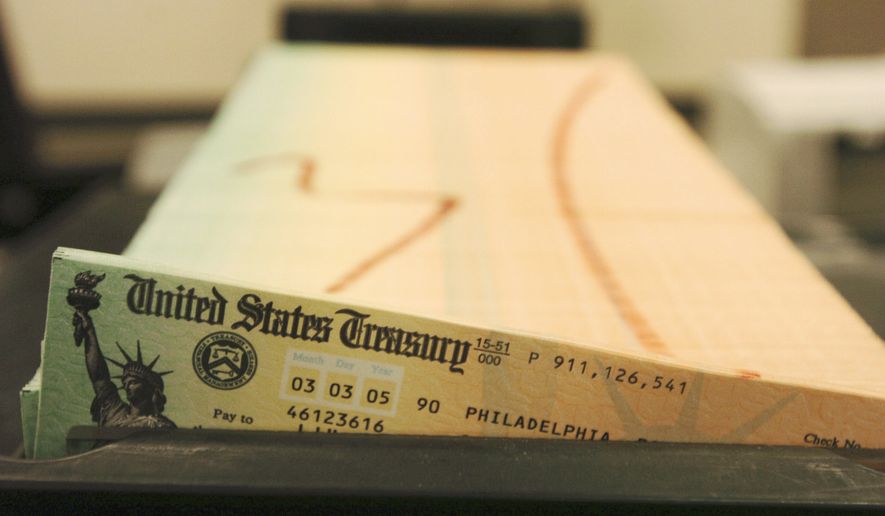

The Social Security Administration was still paying benefits this year to a woman who died nearly 50 years ago, and her nephew had been cashing the checks — collecting a staggering $459,000 over the years, federal prosecutors said Tuesday.

The government also paid out a $1,200 coronavirus stimulus check this year to the woman, who, according to records, would have been 114 years old — the second-oldest person on Social Security.

In actuality, the woman, identified only as AV in court documents, died in Brooklyn in 1971. The government began paying Social Security benefits six years later, in 1977.

The woman was listed as filing a change of address form in 1989, nearly two decades after her death, said Scott Jones, a special agent for the Social Security Administration’s inspector general who investigated the case.

Prosecutors say George Doumar, the woman’s nephew, was cashing the checks — one a month, or more than 500 over 43 years — and keeping the money.

“This case represents one of the highest fraud amounts we have ever seen from a deceased beneficiary case,” said Gail S. Ennis, the inspector general for the Social Security Administration. “This should stand as a warning to anyone who is receiving and misusing Social Security benefits intended for someone else.”

Mr. Doumar admitted the fraud, according to court documents.

When investigators caught up with Mr. Doumar last month, he told them: “What happened was, well she’s passed [away] and, yes, I’ve been collecting her Social Security.”

Mr. Doumar said he did report his aunt’s death to the Social Security Administration in the early 1970s. He said Social Security checks stopped arriving but started again later in the decade, and he began to cash them.

That version didn’t tally with the Social Security Administration’s records, which showed that the woman asked for benefits to start in 1970 though she didn’t become eligible until 1977 — years after her death. Mr. Jones said the Social Security Administration has no record of AV’s death, or of Mr. Doumar’s attempt to report it, in its files.

Mr. Doumar said there were times over the decades when he wanted to stop cashing the checks but figured he would be caught if he did.

He made the address change for his aunt when he moved from New York to Oregon in 1979.

He also admitted to cashing his aunt’s stimulus payment in May.

Thomas A. Schatz, president of Citizens Against Government Waste, said the inspector general recommended in 2012 that the Social Security Administration use data from Medicare and other federal programs to bolster its death records.

That didn’t happen until last year, he said.

“It is disgraceful that this simple process of reporting information from one federal agency to another was not adopted earlier,” he told The Washington Times. “The SSA needs to tighten its review of benefits and the Death Master File system needs to be modernized. The SSA’s inability to remedy these issues in a timely manner has unnecessarily wasted the taxpayers’ money.”

The Social Security Administration told The Times it couldn’t publicly detail its fraud detection tactics but said it does have methods to try to spot bogus payments.

According to court documents, the agency flagged the case after its anti-fraud office singled out AV as the second-oldest person drawing checks, yet she had no updates to her records since the 1989 address change.

Investigators tracked down two nieces who confirmed that AV died decades ago. One of them recalled a nephew who was the beneficiary of her life insurance payout.

Mr. Jones said he found Mr. Doumar, 76, in the Social Security system and discovered he was collecting Social Security benefits under his own name, too, at the same address listed for the deceased aunt. He owned a parcel collection business in Klamath Falls, Oregon, that helped him hide the fraud.

Budget watchdogs say the government regularly sends checks to dead people.

Nearly 1.1 million coronavirus stimulus payments totaling $1.4 billion were sent to dead people in the rush to get the money out the door.

The IRS and the Treasury Department initially argued that they didn’t have the legal authority to stop checks from going to people who had paid taxes in recent years. But after a review, the IRS decided it did have the power and would cancel any uncashed checks issued.

The U.S. attorney for Oregon charged Mr. Doumar with mail theft and theft of public funds. The charges carry a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison.

Chances are he would serve far less time if convicted.

A New Jersey man who collected and cashed his dead grandmother’s checks from 2004 to 2015, totaling $96,000, was sentenced to 10 months of home confinement.

A Texas man who died in 1997 had his checks cashed up through 2015. His daughter was convicted of cashing his checks and sentenced to six months in prison.

• Stephen Dinan can be reached at sdinan@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.