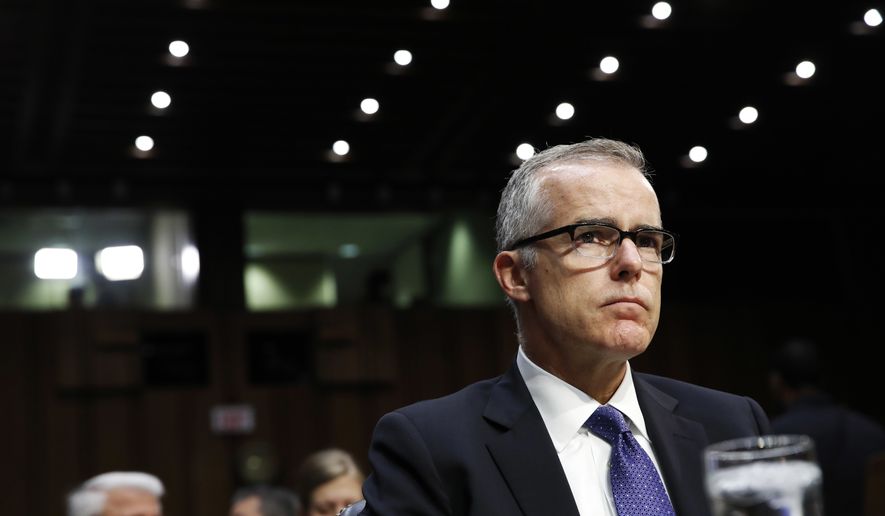

A Justice Department inspector general’s report is the driving force for possible criminal charges against former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, as his attorneys and the department square off in a legal and media showdown.

The inspector general’s 20-month-old findings sparked an ongoing Justice investigation. It said Mr. McCabe lied to fellow agents and cast blame on colleagues for his orchestrated press leak.

His legal team lost an appeal to Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen to avert criminal charges that may come out of the U.S. attorney’s office for the District of Columbia. Defense attorney Michael R. Bromwich floated an unconfirmed rumor that the grand jury refused to indict.

Meantime, Mr. McCabe adamantly rejects the inspector general’s conclusions and is suing the Justice Department.

What did Mr. McCabe do that resulted in his firing in March 2018, a few days short of full retirement, and prompted U.S. Attorney Jessie K. Liu to weigh criminal charges?

Here is what Inspector General Michael Horowitz wrote:

On Aug. 12, 2016, Mr. McCabe received a phone call from the principal associate deputy attorney general in the Obama Justice Department. The inspector general didn’t name the official. Matthew Axelrod, who left Justice shortly after President Trump took office, at the time was associate deputy under Deputy Attorney General Sally Q. Yates.

The call was heated. Mr. Axelrod wanted to know why agents in New York during a presidential election were aggressively investigating the Clinton Foundation, a family charity taking in millions of dollars from foreign sources. The Democratic nominee was Hillary Clinton.

In October, The Wall Street Journal reported on huge campaign donations from a political action committee controlled by then-Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, who is closely tied to the Clintons. The beneficiary was the campaign of Mr. McCabe’s wife, who made an unsuccessful run for state Senate in 2015.

Washington’s chattering class, upon hearing the McCabe story, started questioning FBI objectivity. In July 2016, FBI Director James B. Comey called Mrs. Clinton’s email handling of classified information “extremely careless” but not illegal.

Mr. McCabe launched his own secretive media campaign to counter the bad press. He authorized his counsel, Lisa Page, and a public relations official to contact Devlin Barrett, the Wall Street Journal reporter who wrote the Clinton cash story.

“Are you in with WSJ now,” Mr. McCabe texted to Ms. Page on Oct. 27.

On a second call with Mr. Barrett, Ms. Page filled in the reporter on the Aug. 12 McCabe phone call with Mr. Axelrod.

“We’re done,” she texted Mr. McCabe.

She told Mr. Barrett of the McCabe pushback to show that the deputy was the honest, unbiased G-man the public demanded. On Oct. 30, a Journal story appeared with the headline “FBI Justice Feud in Clinton Probe.”

The story said, in part: “According to a person familiar with the probes, on Aug. 12, a senior Justice Department official called Mr. McCabe to voice his displeasure at finding that New York FBI agents were still openly pursuing the Clinton Foundation probe during the election season. Mr. McCabe said agents still had the authority to pursue the issue as long as they didn’t use overt methods requiring Justice Department approvals.

“’Are you telling me that I need to shut down a validly predicated investigation?’ Mr. McCabe asked, according to people familiar with the conversation. After a pause, the official replied ’Of course not,’ these people said.”

The McCabe media strategy not only disclosed the internal phone call but also marked the first time the government was confirming an FBI investigation into the billion-dollar Clinton Foundation.

Mr. McCabe went further than authorizing the leak. The day the story was published, he telephoned FBI executives at the Washington and New York field offices and blamed his colleagues for the Oct. 30 story.

“Get this house in order,” Mr. McCabe said. He later told investigators he didn’t recall making the calls.

The next day, Mr. Comey convened a high-level meeting to address press leaks. Mr. McCabe later told investigators that he informed the FBI chief about the leaks and Mr. Comey approved. Mr. Comey said no such conversation took place.

Mr. McCabe “definitely did not tell me that he authorized,” Mr. Comey said. “It wasn’t me, boss,” Mr. Comey quoted his No. 2 as saying.

Mr. McCabe also attempted to cast blame in the circle of managers around him and said the fact that Ms. Page was talking to Mr. Barrett was no secret.

In sum, Mr. McCabe attempted to blame Mr. Comey, his field office managers and colleagues around him.

May 2017 was a momentous month for FBI headquarters: Mr. Trump fired Mr. Comey, Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein named Robert Mueller as special counsel for the Trump-Russia election investigation, and Mr. McCabe, now acting director, opened a probe targeting the president as a possible Russian agent. Mr. Mueller’s final report, released in March, showed no evidence that Mr. Trump was an agent.

In the background, FBI internal affairs already was investigating press leaks and added the Oct. 30 Journal story to the mix. During the May turmoil, the inquiry took two FBI internal affairs agents to Mr. McCabe’s seventh-floor office at headquarters.

The agents determined that the acting FBI director’s story didn’t add up and that it was best to move the politically sensitive investigation outside the FBI chain of command to the Justice Department’s inspector general, Mr. Horowitz.

Mr. Horowitz finished his report in February 2018. A month later, with new FBI Director Christopher A. Wray in place, Mr. McCabe was fired based on the inspector general’s findings. The report was released to the public in April.

IG: How Mr. McCabe was untruthful

Mr. Horowitz depicted Mr. McCabe as a manipulative bureaucrat willing to lie about his boss and those around him. According to the inspector general, he:

⦁ Told Mr. Comey on Oct. 31, 2016, that he didn’t approve the leak.

⦁ Denied to FBI agents on May 9, 2017, under oath that he had authorized the October 2016 leak.

⦁ Told the inspector general in July 28, 2017, that he was not aware that Ms. Page was authorized to leak to The Journal.

⦁ Told the inspector general on Nov. 29, 2017, under oath three alleged lies: He acknowledged that he had authorized the leak and contended that he never issued a denial to FBI internal affairs on May 9; he told Mr. Comey that he, Mr. McCabe, had approved the leak; and he said FBI internal affairs agents asked him about the Journal disclosure only as an afterthought as they were leaving his office.

One of the agents who interviewed Mr. McCabe in May 2017 was not happy that his boss spread blame to others for something the deputy director had done.

The agent told the inspector general: “I remember saying to him, at, I said, sir, you understand that we put a lot of work into this based on what you’ve told us. I mean, and I even said, long nights and weekends working on this, trying to find out who amongst your ranks of trusted people would, would do something like that. And he kind of just looked down, kind of nodded, and said, ’Yeah, I’m sorry.’ “

McCabe counterattack

Mr. McCabe rejects the inspector general’s conclusions. He filed suit last month in U.S. District Court alleging that the Trump Justice Department illegally fired him in retaliation for pursuing the Russia investigation.

“Its investigative conclusions are incorrect, partly because the report relies on material mischaracterizations and omissions, including the report’s failure to reference any testimony by exculpatory witnesses,” McCabe attorneys contend.

“[Mr. McCabe] served the FBI with fidelity, bravery, and integrity for more than 21 years, defending the United States against enemies both foreign and domestic,” the lawsuit says.

In contrast, Mr. McCabe’s legal team depicts Mr. Trump as an out-of-control chief executive trying to bully the Justice Department into firing people he doesn’t like.

“It was Trump’s unconstitutional plan and scheme to discredit and remove DOJ and FBI employees who were deemed to be his partisan opponents because they were not politically loyal to him,” the lawsuit says.

Mr. McCabe states that to please Mr. Trump, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions and Mr. Wray fast-tracked the disciplinary process so Mr. McCabe could be fired the day of his planned retirement, denying him full retirement benefits.

Mr. McCabe tells of one encounter with Mr. Trump during the search for a Comey replacement. Mr. Trump wanted to know how he voted in the presidential election. Mr. McCabe says he didn’t cast a vote for president in 2016.

“No superior had ever asked Plaintiff about his voting history in his entire career as a public servant,” the complaint says. “Based on Trump’s tone of voice and body language, Plaintiff understood the question as a threat to his employment, not withstanding his civil service protections, and responded by saying that he ’always played it right down the middle.’ Trump was visibly displeased by Plaintiff’s answer.”

• Rowan Scarborough can be reached at rscarborough@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.