In Washington Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo’s office, there is a framed picture hanging on the wall of a Sports Illustrated cover featuring Stephen Strasburg. It is signed by Strasburg, “Rigs, thanks for caring about me.”

I’m guessing Redskins president Bruce Allen doesn’t have any message of gratitude framed in his office from Trent Williams.

There is no shortage of material to contrast the way the Nationals and the Redskins do business — in case you missed the World Series trophy the Nationals held high during their celebration parade on Saturday — but nothing illustrates the difference between the two organizations more starkly than the treatment of their two star players, Strasburg and Williams.

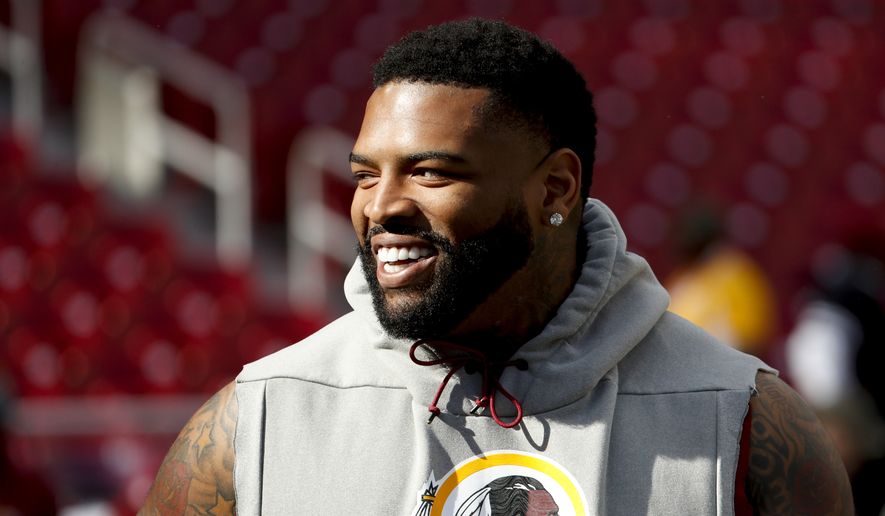

Williams, a seven-time Pro Bowl tackle, has been at war with Allen and the Redskins franchise over the handling of a growth on his head that turned out to be a cancerous tumor that Williams said endangered his life.

He refused to report to the team until recently, with news reports claiming that he blamed the Redskins for the misdiagnosis of the growth in its early stages. When he finally arrived at Redskins Park, Williams outlined how frightening the ordeal was for him — and how he’d lost all respect for the organization that drafted him in 2010.

“It got pretty serious for a second,” Williams said. “I was told some scary things from the doctors. It was definitely nothing to play with. It was one of those things that will change your outlook on life.”

The growth that Williams claimed doctors had told him not to be worried about before had become “far more advanced than they realized, and he underwent what he said was a life-saving procedure.

“We literally caught it within weeks of metastasizing through to my brain to my skull,” he said. “Doing radiology on it would have put a cap on my life. I think 15 years was the most I would have had after I started chemo. So I had to cut it out.”

Williams was angry that the team didn’t look out for him until it was almost too late. “My displeasure comes from how long it lingered and how it was neglected and how it almost cost me my life,” he said.

When Williams first refused to report for mini camp, Allen said he knew the “truth” about what was going on between Williams and the team, but refused to elaborate. When Williams made his public comments last week, the Redskins issued a statement saying they asked for an investigation into Williams’ charges by the NFL Management Council and the NFLPA.

“We have requested this review under the NFL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement that provides for an independent third party review of any NFL player’s medical care,” the statement read. “The Redskins continue to prioritize the health and well-being of our players and staff. Due to healthcare and privacy regulations, we are unable to comment further at this time.”

Since then, Williams has asked the players’ union not to pursue the investigation, which has raised more questions about Williams’ claims. And former Redskins general manager Charley Casserly, an analyst with the NFL Network, reported that Williams had been told three years ago that the growth on his head should be tested and Williams failed to follow through. He also said Williams’ holdout was because he wanted more money.

Unlike Allen, we don’t know what the “truth” is here. But here is what we do know — Williams, one of the most respected players in the league and a team leader, felt compelled to publicly charge that the Redskins nearly cost him his life. That is the message that will resonate with players around the league.

The Nationals had the opposite problem seven years ago. The baseball industry believed that the Nationals cared too much for a player.

That is the only truth that came out of the Strasburg shutdown in 2012, when the Nationals restricted their star pitcher’s innings to 160 that season — their elbow reconstruction surgery recovery program that they utilized the year before with Jordan Zimmerman — which kept Strasburg from pitching in the 2012 National League Division Series against the St. Louis Cardinals.

Never mind that Strasburg had only pitched 147 professional innings — 55 in the minors and 92 in his rookie season, and that he pitched more innings in his shutdown season than his career as a pro. Never mind he had given up 13 runs in 261/3 innings pitched in his last five starts of 2012 before he was shut down. The Nationals were vilified for the move.

Fast forward to 2019 — Strasburg becomes one of the all-time great postseason pitchers after an 18-win season and is named World Series Most Valuable Player. Since he came back from the surgery, Strasburg has a regular season record of 107-55, with 1,370 2/3 innings pitched in 227 starts.

Is this vindication? Nobody can say. No one knows what might have happened if Strasburg had not been held back in 2012 — neither the supporters or the critics. That was the corner Mike Rizzo found himself in. He could never be proven right.

What you could say about Rizzo and the Nationals was that they did all they could to protect a player.

Whatever “truth” comes out about Williams and the Redskins, it’s unlikely anyone is going to accuse Allen of anything similar.

⦁ Hear Thom Loverro on 106.7 The Fan Wednesday afternoons and Saturday mornings and on the Kevin Sheehan Show podcast.

• Thom Loverro can be reached at tloverro@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.