The Trump administration, with a simple change in rhetoric, has signaled a subtle shift in its approach to China in recent weeks — and in the process has deepened a rift with the Communist Party leadership in Beijing.

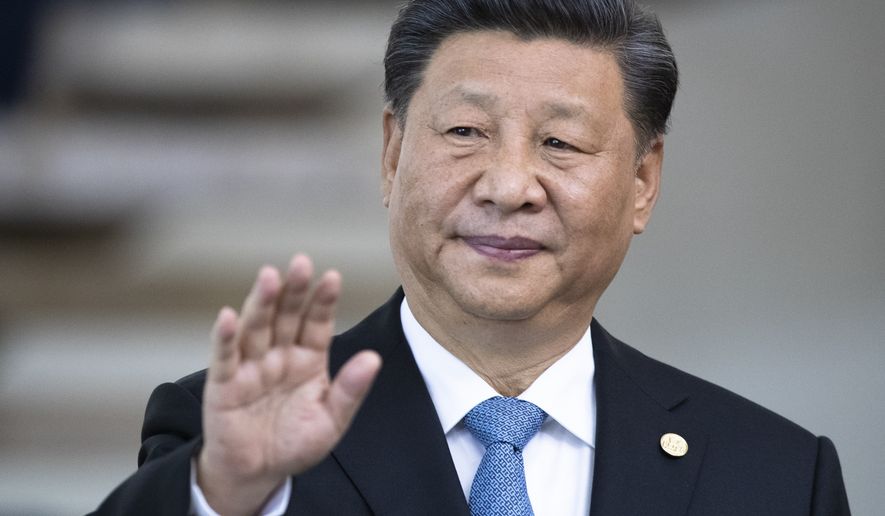

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo delivered a major foreign policy speech late last month in which he referred to Chinese leader Xi Jinping as “general secretary” rather than “president.” The seemingly minor tweak, national security sources and analysts say, carries a much deeper meaning and suggests China hawks in the administration are employing unprecedented bluntness in calling out the lack of democracy and free elections in China.

The policy does not appear to have spread throughout the administration. President Trump referred to “President Xi” when speaking to reporters Tuesday in the Oval Office about the prospects of a trade deal. But sources see growing momentum in Washington to describe the Chinese leader as someone not bound by the will of his people or other democratic checks and balances.

China’s leader technically wears multiple hats. Mr. Xi, 66, is general secretary of the Communist Party of China; president of the People’s Republic of China, a largely ceremonial position making him head of state in protocol terms; and chairman of the powerful Central Military Commission. As part of a concerted drive to cement his power and extend his term, Mr. Xi also secured the title of “core leader” from the Communist Party three years ago.

China in 2018 scrapped the two-term limit for its president, essentially allowing Mr. Xi, who has been in power since 2012, to remain in office indefinitely. Mr. Pompeo’s speech Oct. 30 at the Hudson Institute appears to be the first instance in which a top U.S. official dropped the title “president” when referring to Mr. Xi.

“China’s state-run media and government spokespeople filled the gaps, routinely maligning American intentions and policy objectives,” the top U.S. diplomat said. “They still do that today. They distorted how Americans view the People’s Republic and how they review General Secretary Xi.”

Although Mr. Trump hasn’t changed his language, top White House officials surely cleared Mr. Pompeo’s speech before its delivery.

China’s critics in the U.S. recall the rhetoric of President Ronald Reagan at the height of the Cold War. In his famous 1987 speech at the Berlin Wall, Reagan was careful to refer to “General Secretary Gorbachev” or “Mr. Gorbachev,” underscoring that the only authority his Soviet counterpart could claim was as head of the ruling Communist Party.

The approach has been revamped during a tense time for Washington and Beijing on a host of fronts. The two governments continue negotiations to end a bitter trade war, and top U.S. officials have taken an increasingly tough public line against China’s efforts to claim control of territory in the South China Sea. Mr. Trump on Wednesday signed a bill, passed overwhelmingly in Congress, supporting democratic protesters in Hong Kong.

’Veneer’ of legitimacy

Amid those policy clashes, the U.S. government and the civil society are increasingly pushing to adjust language to describe Mr. Xi. The U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which Congress established in 2000 to report on the relationship between Washington and Beijing, used its most recent report to formally call on the U.S. government to change how it describes Mr. Xi.

“China is not a democracy, and its citizens have no right to vote, assemble, or speak freely,” the commission said in its annual report. “Giving General Secretary Xi the unearned title of ’president’ lends a veneer of democratic legitimacy to the [Communist Party] and Xi’s authoritarian rule.”

The rhetorical change also seems designed to send a clear message to the Chinese population that the U.S. has no quarrel with them and fully supports their economic prosperity. Instead, the administration objects to the Xi government’s growing authoritarian approach.

“And now we know too, and we can see China’s regime trampling the most basic human rights of its own citizens: the great and noble Chinese people,” Mr. Pompeo said in reference to the violent crackdown on protesters by Beijing-backed authorities in Hong Kong.

Analysts say the idea of referring to Mr. Xi as “general secretary” also shines a spotlight on the all-powerful Communist Party of China and its control over domestic debate and policy direction.

“The CCP is excellent at bending the narrative, masters at weaving it into a shield, a spear, whatever beneficial tool is needed,” Robert Spalding, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute who specializes in U.S.-Chinese relations, wrote recently. “If an outsider points out the oppressive nature of China’s controlling party-state apparatus, the outsider is labeled racist. If an economist comments on the CCP’s unfair and predatory economic and trade practices, the economist is trying to keep the Chinese people from reaching their potential.”

A protocol-conscious nation where even the slightest shifts in vocabulary can signal major policy changes, China has been quick to pick up on the language embodied in Mr. Pompeo’s address. Administration sources say top Chinese officials have accused the U.S. of trying to drive a wedge between the Communist Party and the Chinese people.

Chinese officials publicly accused the U.S. of trying to foment unrest in their country.

“To draw a line between the party and the people is to challenge the entire Chinese nation,” Chinese Ambassador to the U.S. Cui Tiankai said last month, according to a summary of his remarks released by the Chinese Embassy.

“Claiming to welcome a successful China on one hand, and defaming and working to overthrow the very force that leads the Chinese people towards success on the other, have you ever seen anything more hypocritical and outrageous than this?” he said at a late October event hosted by the George H.W. Bush Foundation for U.S.-China Relations. “I hope that America’s policies on China will be based on reason and reality, and not be led astray by bigotry and misjudgment.”

The state-controlled Global Times this week specifically called out Mr. Pompeo. It predicted in a lead editorial that his efforts to divide the party from the people would fail.

“Pompeo and his likes,” the online news outlet said, have a “malicious purpose.”

“They are attempting to reduce the Chinese public’s resentment against them by shifting their attacks on China to mainly on the CPC,” the editorial said. “They try to drive a wedge between the Chinese people and the Party, and solicit Chinese domestic endorsement for their criticism. This adjustment is undoubtedly carefully plotted, but only wishful thinking.”

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.