OPINION:

The U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom is a small government agency that has done good work in the past and may do good work in the future — if it’s not transformed into a politicized bureaucracy.

To call attention to this imminent danger, Kristina Arriaga, a USCIRF commissioner since 2016, has resigned, explaining her reasons in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. She cited a proposed reauthorization and “reform” bill introduced in the Senate in September that would shift USCIRF’s “stated purpose and burden commissioners with new bureaucratic hurdles.”

She added: “Following an uproar from Democratic and Republican commissioners, past and present, the senators pulled the bill before it went to the House.” But it’s not over. She is convinced that powerful members of Congress are determined to “erode the commissioners’ independence” and do USCIRF irreparable damage.

To understand what’s happening and why it matters, you need to know a little about USCIRF. It was created 21 years ago at the instigation of Frank Wolf, then a Republican House member from Virginia passionately committed to defending “freedom of religion or belief” in the many countries where that right has been trampled. He also believed in bipartisanship, especially when it comes to foreign policy.

The nine USCIRF commissioners are appointed by either the president or a Republican or Democratic congressional leader. From 2016-18, I was one, appointed by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell.

Commissioners are charged with monitoring the state of religious freedom around the world, and making policy recommendations to the president, the secretary of State and Congress. It’s not a full-time job, and commissioners receive no compensation.

They are meant to be independent, supported by a paid, full-time staff. Though in close contact with the U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom and his deputies at the State Department, they needn’t always agree with them.

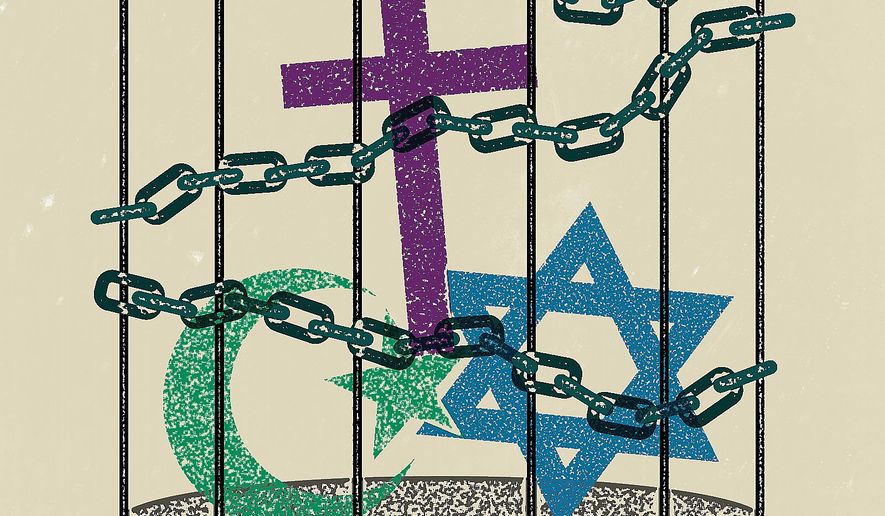

Some members of Congress disapprove of USCIRF. They object to its prioritization of “freedom of religion or belief” — which I regard as the most foundational right, the right upon which all others are built — over what they consider most important: expanding rights for select grievance communities (for want of a better term).

With that in mind, they are proposing to expand USCRIF’s remit to include opposition to “abuse of religion to justify human rights violations.” Think about that: If a Christian baker declines to design wedding cakes for same-sex couples, is that abuse of religion? Is male circumcision a human rights violation justified by abuse of Judaism and Islam?

I think commissioners should avoid such theological questions to the extent possible. They should focus instead on the plight of Muslim Uyghurs in Xinjiang, Buddhists in Tibet, Ahmadis in Pakistan, Baha’i in Iran, Yazidis in Iraq, and Christians in Syria, Egypt and many other lands. On such issues, USCIRF commissioners, Democratic and Republican, can find consensus.

I’m afraid the fight over USCIRF is part of a broader effort to drum conservatives out of the human rights community. Back in July, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo launched a bipartisan Commission on Unalienable Rights to “ground our discussion of human rights in America’s founding principles.” The human rights establishment was outraged, as I detailed in a column at the time.

New Yorker staff writer Masha Gessen argued that Mr. Pompeo lacked credibility because he had once been “a Sunday-school teacher and a church deacon.” Mark Bromley, chair of “an L.G.B.T. foreign policy advocacy group,” told Ms. Gessen that he “fears the State Department is about to create a hierarchy of human rights and will place religious freedom at the top of the pyramid.” He added: “It’s pretty scary.”

Under the “reforms” being proposed, all commissioners would begin and end their terms at the same time, a clever way to ensure that they’d depend on staff to tell them what they can, can’t, should and shouldn’t do.

Another proposal would empower staff to sue commissioners with their lawyers’ fees paid by taxpayers. Commissioners, however, would have to pay defense attorneys out of their own pockets.

Let me explain how this might play out. When I was a commissioner I raised objections about a potential hire. I was skeptical that he could put aside his political views and effectively serve Republican as well as Democratic commissioners. The executive director warned me that I would be violating his rights were I even to suggest disqualifying him on the basis of his politics. But of course she had taken his politics into account when she selected him.

Sen. Marco Rubio has taken the lead on negotiations with Democrats opposed to an independent USCIRF. I’m convinced he’s trying hard to agree only to real reforms and reasonable compromises. I think that should mean increased transparency and strict prohibitions on commissioners monetizing their positions – for instance, by marketing public relations or polling firms in which they have an interest while on USCIRF missions abroad.

What it must not mean is that commissioners become a board of directors or, worse, a board of advisers reporting to administrative state bureaucrats, in particular an executive director who would function as a de facto, alternative ambassador for religious freedom — one not appointed by or serving at the pleasure of the president; one who, according to another proposed “reform,” would receive a higher salary than most members of Congress and U.S. ambassadors.

In this context as in many others, no deal is preferable to a bad deal. But if there is no deal and USCRIF dies, it should be made clear to the public who killed it and why.

• Clifford D. May is founder and president of the Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD) and a columnist for The Washington Times.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.