CAIRO — In a fight over one of the world’s fabled waterways, it’s the Trump administration that is playing the unlikely role of peacemaker.

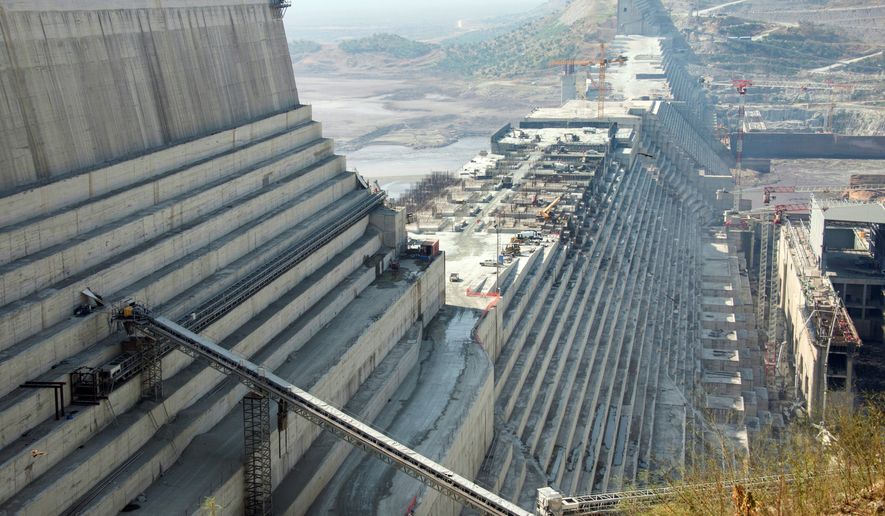

Ethiopia says it needs the proposed 500-foot-tall, $4 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Africa’s largest hydroelectric project, to provide the power for its economic rise.

Egypt says the project will affect the flow of the Nile, its ancient lifeline and the source of virtually all of its water for agriculture, industry and domestic water use, and put control of an indispensable resource in the hands of another country.

The dispute has sparked a war of words between two of Africa’s major powers, including bellicose rhetoric from the just-announced winner of the Nobel Peace Prize.

“If there is a need to go to war, we could get millions [of men] readied,” Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed declared last month in response to threatening words from the government of Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi. Egyptian officials counter that Ethiopia has been unfair by pressing ahead with the project, which broke ground in 2011.

The Nile Basin river system flows through 11 countries. The Blue Nile and White Nile merge in Sudan, which has also been drawn into the dispute, before flowing into Egypt and on to the Mediterranean.

The two leaders met on the sidelines of an Africa summit organized by Russian President Vladimir Putin last month in a bid to lower the temperature, but it was U.S.-mediated talks last week in Washington that may have produced the first signs of a breakthrough.

Treasury Secretary Steven T. Mnuchin and World Bank President David Malpass witnessed top ministers from Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan on Wednesday commit the three nations to expedited direct talks. Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry said in a statement that the three countries hope to reach a deal by mid-January and will appoint an international mediator if they can’t reach an agreement.

With the dam project reaching a critical phase, it’s not a surprise that the Trump administration has stepped in to try to keep the fight under control, according to Mirette F. Mabrouk, director of the Egypt Program at the Washington-based Middle East Institute. Egypt and Ethiopia are populous, well-armed players in the region, significant U.S. business interests are at risk, and Russia has been making a play for greater influence in the region and in Afria generally.

“It is profoundly within the U.S.’s interest to be involved in successful negotiations for myriad reasons,” Ms. Mabrouk wrote in a news analysis Monday. “…If the tragedy of the Syrian war has demonstrated anything, it it that regional conflicts can and do have profound international socioeconomic, political and demographic effects.”

High stakes

For all parties concerned, the stakes could not be higher.

Often referred to by its acronym, GERD, the dam will be the continent’s largest hydroelectric power plant upon its completion slated for next year.

Ethiopia currently rations electricity with blackouts affecting homes and businesses for several hours a day. GERD is set to generate over 6,400 megawatts and transform Addis Ababa into a power exporter.

Egypt relies on the Nile for 90% of its fresh water. It worries that filling the dam’s reservoir will constrict the river’s flow, throw millions of smallholder farmers out of work and threaten the country’s food supply.

“Egypt is concerned that a severe shortage will limit our share of water,” said Ramy Zohdy, a Cairo businessman and foreign relations secretary of the Egyptian Freedom Party, one of several pro-el Sissi groups that dominate the country’s parliament.

A three-year fill time for the reservoir that the dam will create could cut Egypt’s share of the Nile’s waters by 2.64 trillion gallons a year. The shorter the fill time, the more Nile waters flowing downstream are cut off from Egypt and kept in Ethiopia.

A 1959 treaty allocates 14.7 trillion gallons to Egypt and 4.9 trillion to Sudan, but Ethiopia has long complained it was excluded from that agreement. Sudan and Egypt fear the dam will diminish their quota of water needed for agriculture while they struggle to achieve food security and reduce expensive imports of wheat from Russia, the U.S. and Canada.

Then there is the uncertainty.

“Technical errors in construction, filling or operation [of the dam] represent a great danger to Egypt and Sudan,” said Mr. Zohdy. “What if an earthquake caused it to collapse or crack? Additionally, we have environmental concerns, including climate change, all posing the possibility of terrible material and economic losses for Egypt.”

Egypt wants its upstream neighbor to string out the filling of the reservoir for as long as a decade to slow the loss of arable land for agriculture.

Now standing at 100 million, Egypt’s population has nearly doubled since 1985. Despite efforts to direct its citizens to new cities in the desert, and a recent push to promote smaller, two-child families, nearly 200,000 of Nile Valley farming lands are lost yearly to urbanization.

“Besides the reduced amount of water, the main impact for Egypt is increased salinization of the soil,” said Akram Ismail Mohamed, a Cairo engineering consultant who has worked for international construction firms, including engineering giant Bechtel based in Reston, Virginia. “And less water means that fields become saltier and we start to lose even more farming lands.

“Nobody really knows what the impact of the dam will be until after it begins operations,” Mr. Mohamed added. “That’s why it’s reasonable for Egypt to insist that we share common administration of both the GERD and our Aswan High Dam with Ethiopia and Sudan.”

Media-fueled fears

Cairo’s government-directed media is exacerbating widespread fears in Egypt that hostile powers such as Qatar, Turkey and Israel are secretly involved in the dam project.

The Israeli government denied allegations in Egyptian media late last month that it had installed defense systems to deter air raids on the GERD.

“There have been some recent reports that Israeli air defense systems are being used to protect Ethiopia’s Renaissance Dam. … These are just rumors,” the Israeli Embassy in Cairo posted on its official Facebook page.

Some columnists are urging Egypt to draw on its military might to deter Ethiopia from filling the reservoir too rapidly.

“If all diplomatic and legal options fail, a military intervention might be obligatory,” wrote Abdallah el-Senawy, a leading columnist for the pro-government Cairo daily El-Shorouk.

The rising rhetoric reached a peak just days before the Russia meeting between Mr. Ahmed and Mr. el-Sissi when the Ethiopian prime minister, recently awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for winding down the long war with Eritrea, vowed to press ahead with GERD by force if necessary.

“The tensions are not about being jealous of someone’s Nobel Prize,” said Mohammed Hassan, a defense analyst for Cairo’s International Club, a global affairs forum with extensive ties to Egypt’s security establishment. Mr. Ahmed “is the one who raised the prospect of conflict over the dam, not the president of Egypt.”

U.S. financial muscle and the aid of the World Bank may prove critical to a peaceful resolution.

“Egypt is going to need money for massive desalination and water conservation projects to offset the water shortage caused by the dam,” said Mohammed Soliman, an Egyptian nonresident scholar at the Middle East Institute in Washington. “The U.S. Treasury and the World Bank could also engineer steps to promote trade between Ethiopia and Egypt. Increased commerce between the two countries would help to reduce tensions.”

Addis Alemayehu, a principal partner in a marketing and consulting firm that has worked with U.S. companies such as Coca-Cola and Hewlett-Packard to expand their Ethiopian footprints, said the Renaissance Dam has the potential to benefit all countries in the region.

“It’s critical for our future as we develop from an economy that’s based on agricultural production to one centered on knowledge and manufacturing industries,” Mr. Alemayehu said.

“We can both win if we can agree,” he added. “Ethiopia will get badly needed power. Not only can the Egyptians share in that electricity, but a more developed Ethiopia will welcome them as a ready market for their goods and services.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.