President Trump has declared that the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria is “100%” defeated.

It seems unlikely he will ever say the same about Somalia’s al-Shabab.

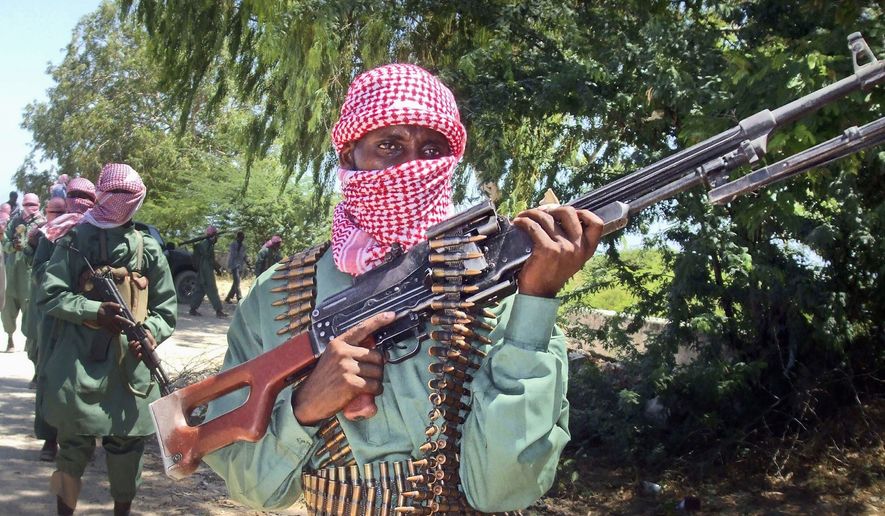

Words such as “eradicate” and “eliminate” — staples of the lexicon used by the Obama and Trump administrations when laying out their ultimate goal in the battle against the Islamic State — are largely absent from the discussion surrounding al-Shabab, the al Qaeda affiliate estimated to control roughly 20% of Somalia and boasting at least 5,000 trained fighters. Analysts say America’s limited policy will never result in a declaration of total victory in the little-understood war, and measuring tangible success in one of the most historically unstable, unpredictable corners of the world will be difficult.

The result: Al-Shabab is not seen as strong enough to make a serious effort to supplant the U.S.-allied government in Mogadishu, but there is also little immediate prospect of ousting the group from its strongholds in southern Somalia and in small pockets of neighboring Kenya and Ethiopia.

“They’re not making the effort to fully beat them,” said Bill Roggio, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies who closely tracks the war in Somalia. “I don’t think you’ll ever see President Trump mentioning Somalia in terms like he did with the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. … You can see that the effort isn’t designed to deal al-Shabab a death blow.”

’Strategic footprint’

The U.S. has waged an intensive air campaign against the group for years and has conducted at least 33 strikes in Somalia this year against al-Shabab and Islamic State targets, according to Pentagon figures. The bombing seems destined to continue for at least two more years. Pentagon leaders are looking at a 2021 handoff to the Somali government and its regional allies.

But over those two years, the approach to al-Shabab likely will remain nuanced. Rather than a crystal-clear end goal to obliterate the group, as was the case with the Islamic State’s “caliphate,” the campaign of airstrikes in Somalia is aimed at providing a safe environment for the Somali people, deterring al-Shabab from expanding and promoting regional security, military leaders say.

“The desired end state in East Africa is one in which terrorist organizations are not able to destabilize Somalia or its neighbors, or threaten U.S. and international allies’ interests in the region,” Maj. Karl J. Wiest, spokesman for U.S. Africa Command, told The Washington Times.

“The effects of our kinetic activities serve to degrade al-Shabab and ISIS-Somalia leadership, disrupt how they communicate and impact their ability to conduct operations,” he said. “We believe the U.S.’s small but strategic footprint approach is sustainable and is enabling incremental progress led” by the government in Somalia.

Military leaders did not provide figures on how effective the air campaign has been in terms of reducing the amount of territory controlled by al-Shabab.

More broadly, there are key differences in the campaigns against the Islamic State and al-Shabab. Chief among them is the U.S. partnership with the Somali government — a stark contrast with measures against the Islamic State in Syria. The U.S. never worked with Syrian President Bashar Assad’s government and even launched airstrikes against the regime in response to reports that Mr. Assad had used chemical weapons against his own people.

But the U.S.-led coalition ultimately defeated the Islamic State and reclaimed virtually 100% of its “caliphate,” which once encompassed much of Iraq and Syria, including a number of major cities.

“You kept hearing it was 90%, 92%, the caliphate in Syria. Now it’s 100%,” Mr. Trump said in February. “We did that in a much shorter period of time than it was supposed to be.”

Such numeric, tangible claims have been mostly absent when officials discuss the campaign against al-Shabab.

Victory will take ’years’

Despite a limited mission and the long history of instability and chaos in Somalia, officials remain optimistic that the U.S. air campaign can keep al-Shabab at bay long enough for the Somali government to make major gains on the ground and perhaps crush the group.

Signs of success include the May 1 liberation of Bariire. The town, African military officials said, was serving as a key transit hub for al-Shabab.

U.S. officials also point to tangible successes. Two years ago, they say, al-Shabab boasted a “freedom of movement” that allowed them to threaten American forces stationed in the coastal town of Kismayo, south of Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu.

That mobility, the military said, has been eliminated. Military outposts have been established in the area to prevent al-Shabab from recapturing the territory, and the Somali government has begun rebuilding infrastructure in the region and allowing some displaced civilians to return to their homes.

Regional analysts, however, remain skeptical that any of those gains will hold without sustained U.S. backing. The current level of American involvement may succeed in keeping al-Shabab at bay, but the group remains resilient.

“If they want to significantly degrade al-Shabab at this level of effort, I just don’t see it happening anytime soon,” Mr. Roggio said. “We’re looking at years, if not decades, because ultimately the Somali security forces — they may be able to clear areas, but their history of controlling areas they take is very poor.”

Some lawmakers on Capitol Hill increasingly share that skepticism and say the Pentagon is wasting time and money intervening in a Somalian civil war.

“Since 2009, the State Department has allocated more than $76 million to provide stipends to the nearly non-existent Somali army,” Sen. Rand Paul, Kentucky Republican, tweeted late last year, citing the government aid as a leading example of a waste of taxpayer money.

U.S. military officials in Africa reject that characterization. They say the government in Somalia and its armed forces have made significant strides in recent years.

Moving forward, analysts say, the U.S. could adopt a clearer, more intensive approach toward al-Shabab, but the idea of a sustained, expensive escalation seems politically infeasible.

“It’s something we could do if we had the political will to do so. We have the military means,” Mr. Roggio said. “A campaign like the one against the Islamic State could be employed in Somalia if the political will to do so was there. There’s just no will to do it.”

• Ben Wolfgang can be reached at bwolfgang@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.