OPINION:

Once upon a time in America baseball was not only the National Pastime, but the national obsession, an idyll of summer. Every town and city had a team. Abbott and Costello made their bones with their classic routine, “Who’s on First?” Baseball was the great equalizer on sandlot and ball park. Everybody knew the words to “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and everybody shared in the enthusiasm for the “home team.”

Baseball was the great equalizer for Jews in the common excitement of the sports culture, as it eventually would be for blacks and Hispanics. But Detroit fans threw pork chops at Hank Greenberg, the Jewish first baseman for the Tigers who came close to breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record that everyone thought would stand forever. He was admired by Jew and Christian alike when he declined on religious principle to play on Yom Kippur during a close pennant race.

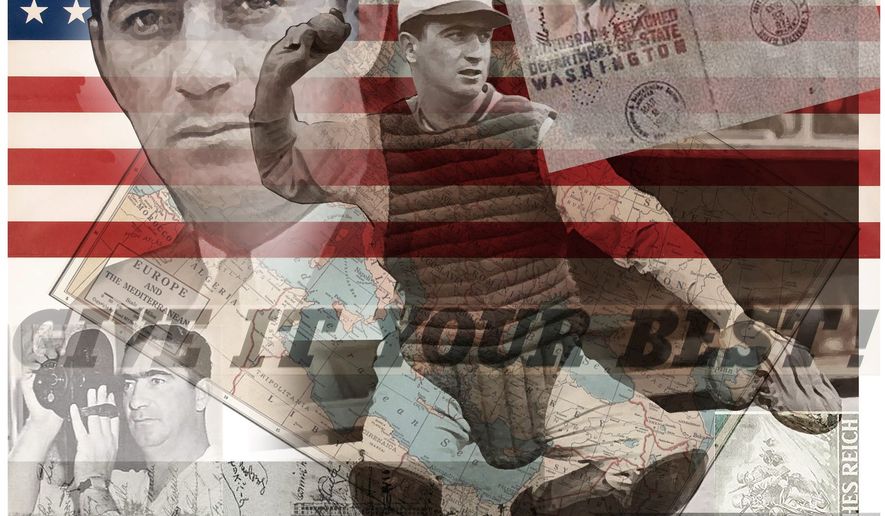

Aviva Kempner, the daughter of Holocaust survivors who makes award-winning documentary movies about Jewish heroes in sports, entertainment and education (including Hank Greenberg), has aimed her camera at another Jewish baseball player in a documentary film called “The Spy Behind Home Plate.” She introduced it on Memorial Day weekend in Washington.

Moe Berg risked his life as a spy, before, during and after World War II. He spent 14 years in the majors, playing for four different teams, including the old Washington Senators when they won the World Series in 1924. The documentary is fascinating and timely, arriving when rank anti-Semitism is emerging again.

We watch Moe carousing with Babe Ruth and a team of all-stars dispatched to Tokyo before World War II to undercut growing Japanese hostility to America. Japanese fans loved the players, including Moe, but the trip fell short of its worthy goal, like a futile ninth-inning rally. Moe, armed with a movie camera, posed as a visitor to get to the roof of a hospital and took panoramic shots of the city. His film was used in the briefing of B-25 crews who flew the famous “thirty seconds over Tokyo” in the early days of the war. He later impersonated a student at a lecture in Switzerland by the chief Nazi scientist at work on an atomic bomb. Moe was armed with a gun and a cyanide pill and instructed to assassinate the scientist if he concluded the Germans were close, and swallow the pill.

Moe was the original “good field, no hit” prospect, but had a rifle arm that few runners dared stealing a base on. He was a student of the game and just about everything else. Casey Stengel called him “the brainiest man in baseball” the “strangest” man he ever knew in baseball. Moe had a priceless gift for handling pitchers. He graduated from Princeton, a brilliant student where “Jewish Princetonian” was almost an oxymoron. A star on the Princeton diamond, he was invited to join an elite eating club with the stipulation that he not attempt to recruit other Jews. Moe declined. He eventually mastered eight languages, including Japanese. He read voraciously throughout his life, forming a habit (which particularly endears him to me) of devouring up to 10 newspapers every day, from the front page to the back, and put what he read to a prodigious memory.

Anti-Semitism is not what it was when Moe encountered it. A few weeks ago San Francisco State University, facing a lawsuit by two Jewish students alleging religious discrimination, said it would spend $200,000 to “promote viewpoint diversity” (including but not limited to pro-Israel and Zionist viewpoints.)

A few college presidents have stood up to mounting anti-Semitism. When the College Council at Pitzer College in California resolved to prohibit an exchange of students with the University of Haifa, the president of Pitzer refused to implement the resolution. When a professor at the University of Michigan refused to write a letter of recommendation for a student who had applied to the University of Haifa, the university disciplined him for “political unprofessionalism.”

But there’s often a refusal to call the ancient evil for what it is. Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives watered down a mild rebuke of Rep. Ilhan Omar for saying Israel had “hypnotized” the world, rewriting it to make it a catchall of criticism of everything hateful. Anti-Semitism is often described in the media as the work of right-wing extremists in both Europe and America, but here it’s usually the work of radical Muslims and anti-Israel ideologues. Felix Klein, the German minister for monitoring anti-Semitism in Germany, says it’s “problematic” to say whether left or right is to blame. But it’s important to denounce anti-Semitism no matter the source, no matter the numbers. It’s a lot more serious than “who’s on first.”

• Suzanne Fields is a columnist for The Washington Times and is nationally syndicated.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.