OPINION:

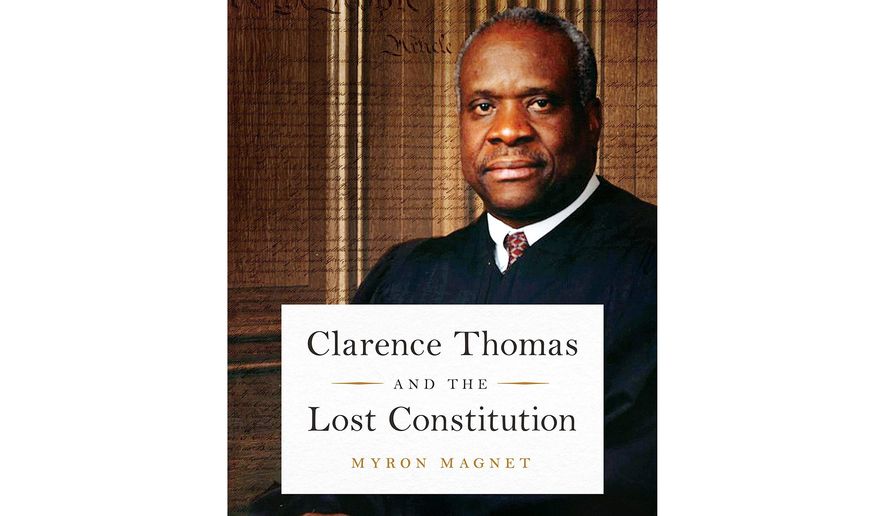

CLARENCE THOMAS AND THE LOST CONSTITUTION

By Myron Magnet

Encounter Books, $23.99, 153 pages

Author Myron Magnet, a recipient in 2008 of a National Humanities Medal, thinks that the United States has for decades been traveling down the wrong road. Following in the footsteps of such other conservative commentators as George F. Will and Neomi Rao, he sees in U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas a man whose personal credo and judicial view of the U.S. Constitution are congruent with his own and an antidote to the worrisome trend.

Although he has a personal and professional relationship with Justice Thomas that goes back years, Mr. Magnet in his new book, “Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution,” makes his case by relying on public Thomas — published interviews and his speeches, journal articles, autobiography and pronouncements from the court, particularly concurrences in which he agreed with the outcome of a case but encouraged his fellow justices to offer bolder, more sweeping, rulings to get to that outcome.

Mr. Magnet finds that “in our age of enraged shrinking violets, in which hypersensitivity to imagined slights alternate with rage against any nonconformity to orthodoxy, Clarence Thomas is one of a handful of honest and brave iconoclasts who love liberty, especially the freedom to think for oneself, and who know how America, imperfect as all human things are imperfect, nevertheless was uniquely conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” It is that conception, embedded in the Constitution, that Mr. Magnet calls “lost” and he lauds Justice Thomas’ continuing striving to recover it.

Justice Thomas’ method, as outlined by Mr. Magnet, “begins with the plain command of the constitutional text or amendment in question, locates it in all the concrete complexity of its historical context, traces the historical process by which the command got distorted from its original meaning, explains the real-world consequences of that distortion, and points out how the Court can repair the damage going forward.”

Mr. Magnet posits three main stages in that distortion from the Founders’ vision.

The first is the string of Reconstruction high decisions that OK’d Southern policies to intimidate freedmen, keep them out of the political process, and assign them to separate spheres of everyday life. He argues that in those decisions the court managed to “overturn the will of the people, through their elected representatives to change the Constitution lawfully and … to embody in the fundamental law of the land the founding proposition that all men are created equal in rights.”

The second stage came when the Supreme Court, after originally striking down 1930s business regulations that affected only local operations — not interstate commerce — and thus beyond the power of Congress, switched course and began promoting an expansive view of the Constitution’s commerce clause. It found enough impact on interstate business to OK the National Labor Relations Act’s control over purely local union-management disputes and even planting allotments for farmers who sold crops to no one at all but fed them to their own livestock; then over the decades it built on and expanded those precedents. Mr. Magnet applauds Justice Thomas’ assertion that the court needs to re-examine this entire 80-year chain of jurisprudence because, the justice wrote, “our case law has drifted far from the original understanding of the Commerce Clause.”

The third transformative development Mr. Magnet spotlights is the rise in number and clout of federal regulatory agencies, agencies he faults as a conceptual error since they combine what the Constitution conceives as three separate powers: They make rules, enforce them and adjudicate violations. Justice Thomas has lamented the growth of this “administrative apparatus that finds no comfortable home in our constitutional structure.” It may, he acknowledges, produce some efficiencies, “but the cost is to our Constitution and the individual liberty it protects.”

Mr. Magnet writes with clarity, liveliness and passion, a combination which is likely to make this book a “right on” pleasure for those who agree with him. But that very passion leads him into excesses. He reaches beyond objective analysis when he says that Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal changes resulted in a country “that resembled George III’s system of ruler and subjects as much as it did George Washington’s government,” and he overstates when he claims the result of affirmative action policies is that “’merit’ is now deemed a racist, sexist construct” or anoints the Justices’ overturning Connecticut’s ban on contraceptives “the most risible Court decision of them all.”

And he repeatedly launches at those with whom he disagrees pejoratives that are both nasty and needless, calling Bill Clinton “debauched,” Barack Obama self-pitying, haughty and elite, and his mother a “flibbertigibbet,” Sen. Dianne Feinstein “endearingly obtuse,” and federal District Court Judge Russell Clark a “megalomaniac.” Those excesses are likely to diminish the impact of “Clarence Thomas and the Lost Constitution” and make it a turnoff for those not already on his side.

• Daniel B. Moskowitz covered the U.S. Supreme Court for BusinessWeek and other magazines.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.