OPINION:

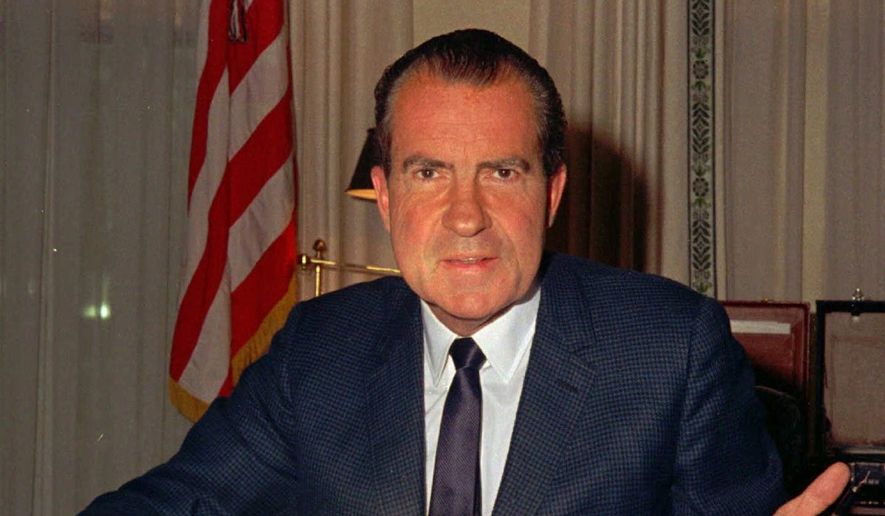

“When the president does it, that means that it is not illegal.”

— Richard M. Nixon (1913-94)

Legal scholars have been fascinated for two centuries about whether an American president can break the law and remain immune from prosecution. During the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln ordered troops to arrest, without warrant, and incarcerate, without due process, many peaceful, law-abiding journalists and newspaper editors — and even a member of Congress — in the Northern states. Wasn’t that kidnapping?

During World War I, Woodrow Wilson ordered federal agents to arrest people who sang German beer hall songs or read aloud from the Declaration of Independence in public. Wasn’t that infringing upon the freedom of speech?

During the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered banks to confiscate gold from Americans who had purchased and possessed it lawfully. Wasn’t that theft?

In the early 1970s, Richard Nixon used the CIA to spy on Americans and to frustrate the FBI’s efforts to investigate a burglary at the Democratic National Committee’s Watergate headquarters, and then he denied doing any of this. Wasn’t that an invasion of privacy and obstruction of justice and using a federal office for deception? Years after his resignation, Nixon infamously told David Frost in a live interview that no matter what the president does, it is lawful. Where did he get that argument from?

And President Donald Trump has asked Congress for money to condemn real estate and build a border barrier in Texas. Congress said no, yet he plans to spend the money anyway. Doesn’t that violate his oath to uphold the U.S. Constitution?

Though there may have been political consequences to each of these presidential acts of lawlessness — there were for Nixon, at least — there were no legal consequences in the form of impeachment or prosecution. The Constitution itself limits impeachment to treason, bribery or other high crimes and misdemeanors.

The “high crimes and misdemeanors” language was interpreted by the House Judiciary Committee in 1974 to include material interference with a governmental function and obstruction of justice and the use of a governmental asset to deceive the public — but not any garden-variety crime, such as bank or tax fraud or kidnapping or invasion of privacy or misappropriation of federal funds.

During the presidency of Bill Clinton and afterward, the Department of Justice ordered research about whether a president could be charged with a crime against his will and while still in office. The DOJ now possesses three scholarly legal opinions on the subject. Two of them say he cannot be prosecuted; one of them says he can. All three are based on the same law and history but employ different deference to the presidency.

Two of those opinions say that if there is probable cause of crime by the president and the time during which the law requires a prosecution to commence — the statute of limitations — would expire while the president is in office, he or she should be indicted while in office but the prosecution should be deferred until he or she is no longer president. One of the opinions, incredibly, mimics the Nixonian president-as-prince idea and basically tells the Department of Justice to forgo prosecution.

Mr. Clinton was prosecuted while in office for testifying falsely — lying under oath in a civil deposition, a crime rarely prosecuted — but it was with his consent. Presumably, he consented to the quick prosecution and guilty plea in the final days of his presidency to avoid a costly and prison-exposed post-presidential indictment for more serious crimes.

I have recounted this brief history of presidential lawbreaking as a background to a discussion of the political period I suspect we are all about to enter. That period will commence with the expected release of the report of special counsel Robert Mueller. Under the court rules through which he was appointed, however, his report is not for Congress or the president or the public but rather for the attorney general and those engaged by him to analyze it.

There may be parts of the report that could not lawfully be made public. For example, if a grand jury took testimony about the president’s alleged and denied obstruction of justice related to his firing of FBI Director James Comey — i.e., testimony about whether he did so for a venal or unlawful purpose, such as preventing the FBI from discovering other presidential crimes — and the grand jury decided not to indict the president, the existence of that testimony, as well as its substance, must remain secret under the law. The same is the case for all references to a decision not to indict someone.

That is at least the theory of grand jury secrecy; those not indicted should not have their names dragged through the mud.

Now back to Nixon’s the-president-can-commit-no-crime argument and that DOJ opinion basically agreeing with it. This view of the presidency is imperial. Is the president of the United States so integral to the preservation of the Constitution that he cannot be diverted from that job to the rigors of defending himself or herself in a criminal prosecution?

If the answer is yes, how about when he or she is no longer employed in the defense of the Constitution? If the answer to this question is no, who should be trusted with a get-out-of-jail-free-forever card? And where is that in the Constitution?

Mr. Trump once boasted that he could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue in New York City in broad daylight and get away with it or pardon himself. I hope this was Trumpian comedic exaggeration. If not, it is the revelation of a dangerous Nixon-like mentality that the rule of law — which requires that no one be above the law’s commands or beneath its protections — applies to everyone but him.

Can the president legally break the law? If he can, we will soon be back to the Nixon days. And we all know how they ended.

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.