DUBAI, United Arab Emirates — The boy is only 12 years old and looks even younger and smaller kneeling next to the wreckage of a helicopter, flanked by masked jihadis carrying Kalashnikov assault rifles with bandoliers strapped across their chests.

Hamza bin Laden, with a traditional Arab coffee pot to his right and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher to his left leaning against the debris, made his worldwide television debut reciting a poem in a propaganda video just weeks after the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks planned by his father Osama.

Years after the death of his father at the hands of a U.S. Navy SEAL raid in Pakistan, it is now Hamza bin Laden who finds himself squarely in the crosshairs of world powers. In rapid succession in recent weeks, the U.S. put a bounty of up to a $1 million for him; the U.N. Security Council named him to a global sanctions list, sparking a new Interpol notice for his arrest; and his home country of Saudi Arabia revealed it had revoked his citizenship.

Those measures suggest that international officials believe the now 30-year-old militant is an increasingly serious threat. He is not the head of al Qaeda but he has risen in prominence within the terror network his father founded, and the group may be grooming him to stand as a leader for a young generation of militants.

“Hamza was destined to be in his father’s footsteps,” said Ali Soufan, a former FBI agent focused on counterterrorism who investigated al Qaeda’s attack on the USS Cole. “He is poised to have a senior leadership role in al Qaeda.”

Much remains unknown about him - particularly, the key question of where he is - but his life has mirrored al Qaeda’s path, moving quietly and steadily forward, outlasting its offshoot and rival, the Islamic State group.

’LIVING, BREATHING’ AL-QAEDA

Hamza bin Laden’s exact date of birth remains disputed, but most put it in 1989. That was a year of transition for his father, who had gained attention for his role in supplying money and arms to the mujahedeen fighting the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s. Osama bin Laden himself was one of over 50 children of a wealthy, royally connected construction magnate in the kingdom.

As the war wound down, bin Laden emerged as the leader of a new group that sought to leverage that global network brought together in Afghanistan for a new jihad. They named it al Qaeda, or “the base” in Arabic.

Already, bin Laden had met and married Khairiah Saber, a child psychologist from Saudi Arabia’s port city of Jiddah who reportedly had treated bin Laden’s son by another wife, Saad, for autism. She gave birth to Hamza, their only child together, as al Qaeda itself took its first, tentative steps toward the Sept. 11 attacks.

“This boy has been living, breathing and experiencing the al Qaeda life since age zero,” said Elisabeth Kendall, a senior research fellow at Pembroke College at Oxford University who studies Hamza bin Laden.

Hamza, whose name means “lion” or “strength” in Arabic, was a toddler when the bin Ladens’ life in exile began. They moved to Sudan after bin Laden’s criticism of the kingdom hosting American forces during the 1991 Gulf War alienated the Al Saud royal family.

Under growing international pressure after bin Laden declared holy war on the U.S., Sudan pushed him out and the family moved again to Afghanistan in 1996. Hamza bin Laden was 7.

Al Qaeda’s attacks against the U.S. began in earnest in 1998 with the dual bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania that killed 224 people. Its 2000 suicide attack against the USS Cole off Yemen killed at least 17 sailors.

Hamza bin Laden appeared in photographs alongside his father or in propaganda videos in this time, hanging from monkey bars in military-style training or reciting a poem in classical Arabic, garbed in a camouflage vest.

Then came Sept. 11, 2001. The coordinated al Qaeda hijacking sent two U.S. commercial airliners slamming into the World Trade Center in New York, one striking the Pentagon and another crashing in rural Pennsylvania, all together killing nearly 3,000 people.

So at age 12, Hamza bin Laden appeared in the video above the wreckage of a helicopter, likely a remnant of the Soviet occupation, not a U.S. warplane as al Qaeda claimed at the time.

He recited a poem praising his father’s ally, Afghan Taliban leader Mullah Mohammed Omar, as the “lion of Kabul,” ran in a field with other boys and held a pistol above his head as if fearless of American airstrikes. It marked the last moments before the U.S.-led invasion would topple the Taliban and send Osama bin Laden fleeing into the mountains of Tora Bora and, from there, Pakistan.

Hamza later remembered receiving prayer beads from his father with his brother Khalid before leaving him.

“It was as if we pulled out our livers and left them there,” he wrote.

And then, like his father, Hamza bin Laden disappeared.

THE IRAN YEARS

Hamza bin Laden and his mother followed other al Qaeda members into Pakistan amid the U.S.-led coalition bombing campaign on Afghanistan. From there, they crossed into Iran, where other al Qaeda leaders hid them in a series of safe houses, according to experts and analysis of documents seized after the U.S. Navy SEAL team raid that killed the elder bin Laden in the Pakistani town of Abbottabad.

The connection between al Qaeda and Iran has been a murky one, firmly disputed by Tehran. Iran, the Mideast’s predominant Shiite power, on its face seems a strange home for the Sunni Arab militants. Sunni extremists views Shiites as heretics and target them for violence.

But al Qaeda under Osama bin Laden made inroads with Iran during his days in Sudan, according to the U.S. government’s 9/11 Commission. The commission said al Qaeda militants later received training in Lebanon from the Shiite militant group Hezbollah, which Iran backs to this day.

Before the Sept. 11 attacks, Iran allowed al Qaeda militants to pass through its borders without receiving stamps in their passports or with visas obtained at its consulate in Karachi, Pakistan, according to a 19-page, unsigned report found among Osama bin Laden’s personal effects in the Abbottabad raid. That helped the organization’s Saudi members avoid suspicion. They also had contact with Iranian intelligence agents, according to the report.

Iran offered al Qaeda fighters “money and arms and everything they need, and offered them training in Hezbollah camps in Lebanon, in return for striking American interests in Saudi Arabia,” the report said.

This matches up with the 9/11 Commission’s report, which found that eight of the Sept. 11 hijackers passed through Iran before arriving in the United States. However, the commission “found no evidence that Iran or Hezbollah was aware of the planning for what later became the 9/11 attack.”

It’s unclear why Iran allowed the al Qaeda members, including bin Laden’s children and wives, to enter the country immediately after the 9/11 attacks. Iran’s president at the time, the reformist politician Mohamed Khatami, and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei condemned the attack, and Iran helped the ensuing U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan. However, by January 2002, U.S. President George W. Bush declared Iran as part of an “Axis of Evil” alongside Iraq and North Korea.

Iran’s mission to the United Nations did not respond to a request for comment.

By April 2003, just weeks into the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq that toppled Saddam Hussein, Iranian intelligence officials had had enough of al-Qaida being beyond their control. It rounded up all the al-Qaida members it could find and detained them, apparently at a series of military bases or other closed-off compounds, according to contemporaneous accounts by several al-Qaida militants.

CAPITVITY

In Iran, Hamza’s mother Khairiah Saber urged the al Qaeda lieutenants there to take her son - now a teenager - under their wing. Hamza wrote to his father recounting the Islamic theology books he studied in detention, while expressing frustration that he was not among the jihadis in battle.

“The mujahedeen have impressed greatly in the field of long victories, and I am still standing in my place, prohibited by the steel shackles,” Hamza wrote in one of his letters found at Abbottabad. “I dread spending the rest of my young adulthood behind iron bars.”

But those shackles ended up keeping him and the other al Qaeda members safe as the U.S. under Bush and later President Barack Obama targeted militants across the Mideast in a campaign of drone strikes. Hamza’s half brother Saad escaped Iranian custody and made it to Pakistan, only to be immediately killed by an American strike in 2009.

“That probably saved (Hamza) that he was in Iran during that period where everyone else was being knocked off, detained,” said Tricia Bacon, an assistant professor at American University who focuses on al Qaeda and once worked in counterterrorism at the State Department. “It probably was one of the better places to be able to re-emerge at a later time.”

Hamza during this time even married into al Qaeda, picking a daughter of Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, an Egyptian who the U.S. says helped plan the November 1998 embassy attacks. The two had two children, Osama and Khairiah, named after his parents.

“I ask God to place their image in your eye,” Hamza wrote his father. “He created them to serve you.”

By this time, rumors of al Qaeda members being in Iran had reached a fever pitch. A teenage daughter of Osama bin Laden, Eman, somehow escaped imprisonment in late 2009 and made her way to the Saudi Embassy in Tehran. Iran’s then-Foreign Minister Manouchehr Mottaki said at the time: “We don’t know how this person went to the embassy or how she entered the country.”

Khalid bin Laden, another son of the wanted terrorist, later would write a letter that was posted online and addressed to Iran’s supreme leader saying his siblings were “beaten and repressed.”

After years of imprisonment, an opportunity emerged for the al Qaeda members held in Iran. Gunmen in late 2008 kidnapped an Iranian diplomat in northwestern Pakistan. He would be freed in March 2010 as Hamza and others also left custody.

Osama bin Laden thought of sending Hamza to Qatar for religious scholarship, but his son instead went to Pakistan’s Waziristan province, where he asked for weapons training, according to a letter to the elder bin Laden. His mother left for Abbottabad immediately, where her husband was in hiding, with Hamza hoping to come as well.

But on May 2, 2011, the Navy SEAL team raided Abbottabad, killing Osama bin Laden and Khalid, as well as others. Saber and other wives living in the house were imprisoned. Hamza again disappeared.

REEMERGENCE

In August 2015, a video emerged on jihadi websites of Ayman al-Zawahri, the current leader of al Qaeda, introducing “a lion from the den of al Qaeda” - Hamza bin Laden. The younger bin Laden was not shown in the video, speaking only in an audio recording. With a voice deepened from the tinny recitals he offered as a child, he praised al Qaeda’s franchises and other militants.

“What America and its allies fear the most is that we take the battlefield from Kabul, Baghdad, and Gaza to Washington, London, Paris, and Tel Aviv, and to take it to all the American, Jewish, and Western interests in the world,” he said.

Since then, he has been featured in around a dozen al Qaeda messages, delivering speeches on everything from the war in Syria to Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia on his first foreign trip as U.S. president. His style resembles his father’s, with references to religious studies and snippets of poetry, a contrast to the gory beheading videos of the Islamic State group, which had risen up from al Qaeda in Iraq to seize territory across Iraq and Syria.

“He’s not blood and guts,” said Kendall, the senior research fellow at Pembroke College at Oxford University. “His speeches are more literary and educated.”

While al-Zawahri still controls al-Qaida, the multiple messages have raised speculation that the terror group may be trying to plan for the future by putting forward a fresh face - albeit one they have so far only showed in old photographs of Hamza bin Laden as a child.

Meanwhile, the Islamic State group has seen its territory slip away as it was pounded by a U.S.-led coalition, Russian airstrikes and Iranian-backed forces.

That has left al Qaeda as the prominent jihadi group standing.

“I think as ISIS’ strength continues to deteriorate, the international community has perhaps realized that there are other terrorist groups - including the ones that never went away, such as al Qaeda,” said Sajjan Gohel, the international security director of the United Kingdom-based Asia-Pacific Foundation, using another acronym for the Islamic State group.

“In fact, al Qaeda has been quietly growing, regaining strength, letting ISIS take all the hits while they quietly reconstitute themselves,” he added.

The State Department named Hamza bin Laden as a “global terrorist” in 2017, then followed up in February with the bounty on his head as the U.N. blacklisted him.

The designations show officials consider him a threat.

“There is probably other intelligence that indicates something’s happening and that’s what put this thing on the front burner,” said Soufan, the former FBI agent.

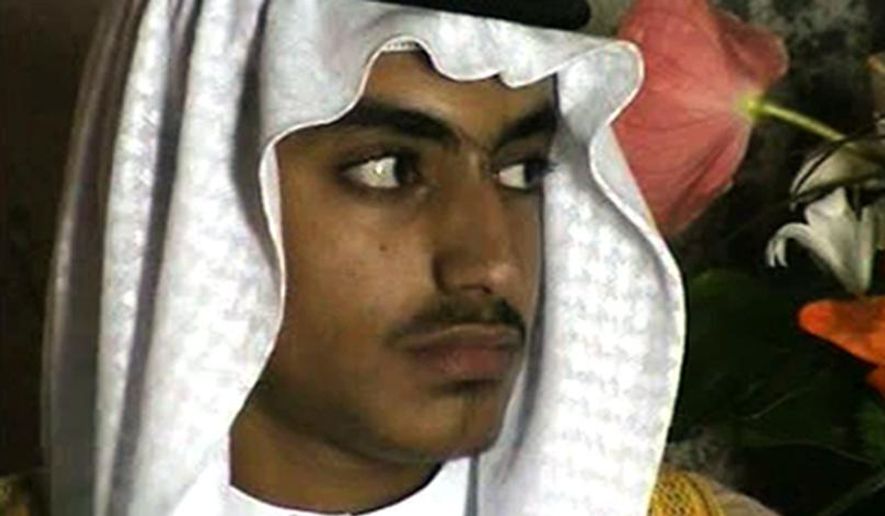

But what’s happening within al Qaeda remains a mystery. Hamza bin Laden hasn’t been heard from since a message in March 2018, in which he threatened the rulers of Saudi Arabia. Why remains in question. Rumors have circulated he himself was targeted in an attack. The CIA also published video of him in November 2017 at his wedding in Iranian detention, showing the first publicly known photographs of him since childhood.

An image from that video now graces his U.S. wanted poster.

“Will he be successful? We don’t know. Will he live long to do what his father was able to do? We have no idea. We might drone him tomorrow,” Soufan said. “But this is the plan. This is what they wanted to do. This is what he is destined, I believe, to do from the beginning.”

• Associated Press writer Maamoun Youssef in Cairo contributed to this report.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.