OPINION:

The National Institute of Mental Health reports that nearly one in five U.S. adults suffers from a disorder of the mind, ranging in severity from mild to nearly incapacitating, and that in 2016, only 19.2 million of the 44.7 million struggling with “any mental illness” at all — abbreviated in medical lingo as AMI — went for help.

In 2013, meanwhile, America spent almost $188 billion on mental health and substance abuse disorders, according to the American Psychological Association.

That means treatments are costly — but if demand were truly being met, treatments would be even costlier.

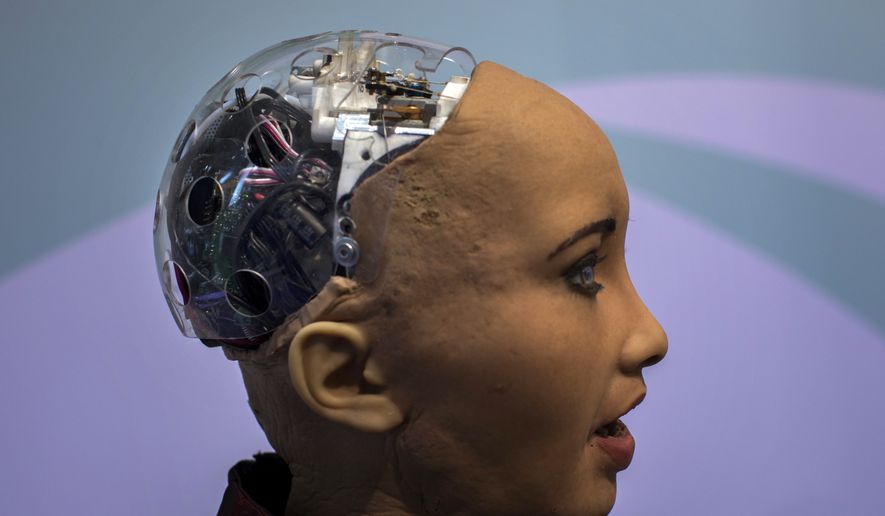

So here comes technology offering a solution.

Scientists say it won’t be long before machine-learning systems take much of the guesswork out of mental diagnoses and eventually even identify correlations between sicknesses of the mind and physical symptoms of the body, so as to make labeling and treating faster and easier.

Hair-raising? A bit.

A machine that tells what’s wrong with your mind based on responses given by your body does seem on the freakish-slash-frightening side of the emerging technology world.

Still, it’s not all bad. Not all technology in the mental health world has to be seen as “eee-vul.”

Certainly, chatbots, for instance, could provide some sufferers a bit of solace. For those with depression, those who are lonely and even suicidal, those poised for panic attacks — for those and others, the ease and rapidity with which a quick in-home consultation-slash-session could be arranged, with the simple flip of an Internet connection, are positives that are hard to dispute.

Certainly, the old well-worn, oft-overly used phrase, “If it saves just one —” could apply here.

And certainly, any privately tapped A.I. that guides a mentally anguished individual back to safety and sanity — when that same individual might resist going to a therapist’s office and therefore miss out on the necessary help — well, that’s not just good for that person. It’s also good for the community and society at-large.

But, the negatives of mind-diagnosing A.I. seem fraught with pitfalls and dangers, particularly when peering down the path of unintended consequences.

First off, think of the data collection.

That’s the lifeblood of any A.I. system; if due diligence and utmost care aren’t exerted, the privacy dings to unsuspecting citizens could prove disastrous and outrageous.

But second off, think of the potential for over-reliance.

As with any A.I. in the medical sector, it’s one thing for a physician to use a scan or a test result to bolster human research and findings. It’s another thing entirely to turn over the testing and researching and diagnosing to a machine — learned as that machine may be. It’s another thing to rely so heavily on an A.I. finding that it becomes the main course of action the medical professional takes. And it’s decidedly different in the world of physical health compared to the world of mental health.

A patient wrongly diagnosed by A.I. as a high risk for cancer and subsequently placed on a low-fat diet by the doctor potentially loses out on some junk food.

But a patient wrongly diagnosed by A.I. as suicidal and subsequently directed to a treatment facility for further evaluation? That patient could not only lose precious freedom, but he or she could be labeled for life with a condition of the mind that, depending on which way the political pendulum swings, might lead to denials to fly, denials to enter certain buildings, denials of security credentials, denials to obtain certain jobs — even denials to purchase or own firearms.

Mental illness can be a stigma that sticks, even when it’s based on disputed psychology. Just ask a member of the military who swallows the post-traumatic stress disorder rather than suffer the potential career stain by seeking treatment.

Fact is, inviting technology to take over, even in small part, a field that’s so open to human interpretation, that’s so dependent on comparisons and degrees and contextual analyses, that’s already so vulnerable to human error, human guesses, just seems a nail-biter of a game.

And, as we may find, sadly too late, it may not be one that’s even worthwhile to play.

• Cheryl Chumley can be reached at cchumley@washingtontimes.com or on Twitter, @ckchumley.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.