OPINION:

ATHENS — After Greece temporarily hosted a pair of U.S. military drones, Greek Defense Minister Panagiotis Kammenos said last fall that, “It’s very important for Greece that the United States deploy military assets in Greece on a more permanent base.”

Indeed, Greece just took delivery of some 70 military helicopters that it had purchased from the United States, and there have been discussions about basing American drones, air tankers and other military aircraft on Greek soil.

COSCO, a state-owned Chinese shipping and logistics services company, has invested more than 3.5 billion euros in renovating the historic Greek port of Piraeus, which is now the second-largest port in the Mediterranean. The Chinese brag that it will soon become the busiest. The massive renovation is part of China’s 35-year lease of two of the port’s container terminals and the Chinese purchase of a majority stake in Piraeus’ port authority.

Despite recent spats, Vladimir Putin’s Russia remains a supposed ally of Greece, given historic religious ties and the envisioned completion of a natural-gas pipeline that will supply Russian gas to energy-starved Greece.

Greece has a complicated relationship with its European Union partners after its catastrophic financial meltdown and the often Dickensian terms of reform and repayment demanded by German bankers. Yet Greece appreciates that more European Union money goes into the country than goes out, even if many Greeks resent bitterly high-handed German dictates — and being manipulated as the frontline transit center for hundreds of thousands of migrants swarming into Europe from Africa and the Middle East.

New Greek freeways are less congested and more impressive than California’s, despite the fact that Greek GDP is less than one-twelfth that of California.

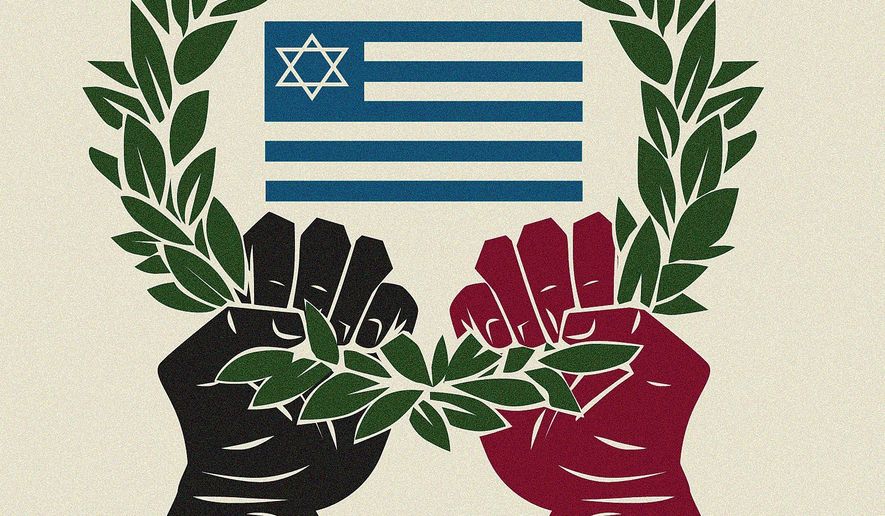

During the 1970s and 1980s Greece was more or less anti-Israel (like much of Europe). Not any longer. The two countries are becoming fast friends.

Greece’s new multifaceted foreign policy might be best summed up by 19th-century British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston’s famous dictum: “Nations have no permanent friends or allies, they only have permanent interests.”

Greece seems to have found lots of semi-permanent interests.

In other words, relatively small and vulnerable but strategically located Greece lives in a tough neighborhood with historic enemies such as Turkey and radical Islamic groups. As a window on the Mediterranean and three continents, Greece sits at the intersection of great-power rivalries between Europe, America, China and Russia.

In the old days, Greece, a member of both NATO and the EU, grumbled that its European and American big brothers took it for granted as either an insignificant subordinate or a whiny nuisance — despite its key location and its iconic status as the birthplace of Western civilization.

Now, things have changed — and often to Greek advantage.

Greece has gone from its traditionally defiant (if not insecure) role as an outlier to that of a crafty insider. There are lots of reasons for the new Greek realpolitik, besides learning from the vulnerability of its past dependencies.

The rise of a neo-Ottoman Turkey, with a population seven times that of Greece, a territory six times as large and renewed territorial ambitions in the Greek Aegean, has made Greece turn to the U.S. military for protection. America, too, is increasingly wary of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Islamist, anti-American and Mediterranean agendas.

Instead of trusting fellow EU members, Greece has merely found them useful in scheduling its debt repayments and providing critical tourist dollars.

Doing business with China is dangerous, given Chinese neo-imperial schemes that occasionally have led to blatant Chinese blackmail and bullying of its vulnerable clients. But the Chinese presence has pumped billions of euros into the ailing Greek economy while reminding the EU that Greece has other options when it comes to foreign investment, infrastructure and trade.

Few nations trust the reptilian Putin. But when the Russian president poses as a defender of Orthodox Christianity and as a protector of Eastern Europe and the Balkans from German bullying and Islamic troublemaking, the Greeks may find him useful in supplying energy and in foreign-policy triangulation.

Israel has also been recalibrated as a useful asset for democratic Greece. Like other traditionally persecuted peoples, the Greeks and Israelis share a mistrust of great powers. Israel now plans to build a massive underwater pipeline to link its natural gas supplies with Greece and Cyprus.

Both Greece and Israel have resentments against the European Union. Both have given up on detente with Mr. Erdogan’s bellicose Turkey. Both count on U.S. military aid. Both no longer are so dependent on unstable Arab countries for imported gas and oil.

Greece is, of course, walking a tightrope. By balancing between rivals and finding new friendly interests, Greece magnifies its own importance. As it does, it also becomes an even greater focal point of big-power rivalries and global commercial jostling.

We should not be too surprised by Greek realpolitik. After all, Greece gave the world Themistocles, the fifth-century B.C. wheeler-dealer politician and general who increased ancient Athenian power by being interested in everyone — and permanently allied to no one.

• Victor Davis Hanson, a classicist and historian at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, is the author of “The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won” (Basic Books, 2017).

Please read our comment policy before commenting.