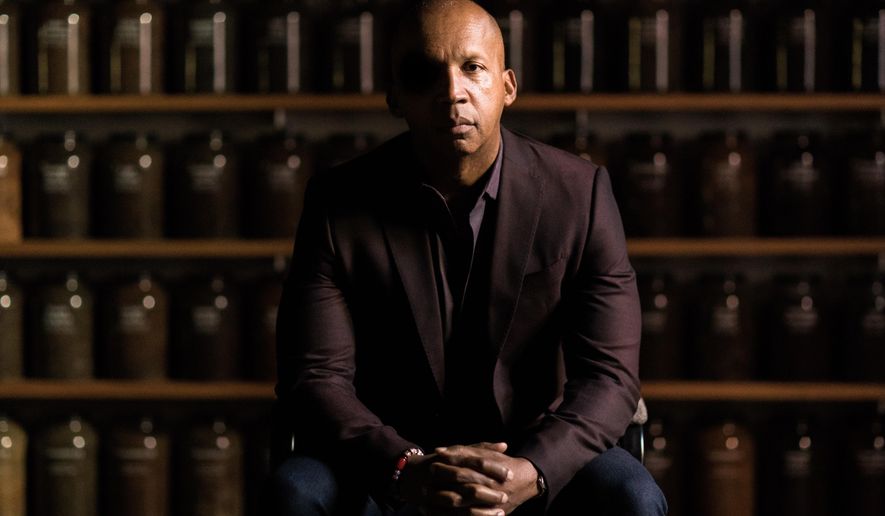

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (AP) - Civil rights attorney Bryan Stevenson rarely slows down, friends and family say. It seems he’s always looking over details on death penalty cases from his Montgomery, Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative. If he’s not speaking on the criminalization of black men, Stevenson is researching another historical site connected to an episode of racial violence.

But a new HBO documentary on Stevenson attempts to get him to sit, speak and explain why he believes the legacy of lynchings of African Americans in the U.S. is directly linked to those who have wrongly been put on death row. In his mind, racial structures of oppression have remained in the U.S. judicial system since the Jim Crow-era and the death penalty is merely their direct descendant.

“Most people don’t know about our history of lynching,” Stevenson told The Associated Press in a phone interview shortly after receiving news Friday that the Supreme Court had overturned the death sentence for Curtis Flowers , a Mississippi black man. “People have never been required to talk about it. But when you sit and think about it, the correlation is there.”

Stevenson said the white lynch mob transformed into a formal judicial process in which often white prosecutors, white judges and largely white juries are tasked with deciding if a poor, black male accused of a crime is sentenced to death.

“True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality,” set to air Wednesday on HBO, shows how the Harvard-trained attorney is now dedicating his life to forcing the U.S. to face the violence experienced by its communities of color.

The Delaware-born Stevenson gained national attention in 1993 after he helped exonerate Walter McMillian, a 46-year-old black pulpwood worker on death row. McMillian had been sentenced to death for the 1986 fatal shooting of an 18-year-old white woman in an Alabama town where Harper Lee wrote “To Kill a Mockingbird.” But Stevenson was able to prove that a key witness had lied and prosecutors withheld important evidence.

The attorney then helped exonerate Anthony Ray Hinton in 2015, an African American man who spent 30 years on death row in Alabama after he was convicted for the 1985 slaying of two fast-food managers. Stevenson was able to show that experts could prove Hinton’s mother’s gun, the one prosecutor said was using in the killings, couldn’t have been the one used in the shooting.

In the documentary, Hinton talks about sitting on death row and being forced to smell the burning flesh of other inmates in the electric chair as a jail guard taunted him.

The film comes as the country prepares to mark the 100th anniversary of “Red Summer” - a period in 1919 when white mobs attacked and murdered African Americans in dozens of cities across the U.S. Hundreds of African Americans, some still in their World War I uniforms, were lynched, tortured and forced from homes amid heightened racial tensions and the rise of the revived Ku Klux Klan.

It also comes as Latino academics and activists with the group Refusing to Forget are working to educate the public on violence committed by white mobs and the Texas Rangers that claimed thousands of people of Mexican descent in the American Southwest from 1910 to 1920.

Stevenson said he hopes the documentary helps other communities of color think about how they can memorialize historical sites connect to their unique past. But he said African Americans have a distinct history connected to slavery and that should not be ignored.

“This kind of lawlessness affected all kinds of communities of color,” Stevenson said. “But it’s not the same. Lynching starts with enslavement. Black people didn’t come here as immigrants.”

“True Justice” will be available on HBO NOW, HBO GO, and other streaming platforms.

___

Russell Contreras is a member of The Associated Press’ race and ethnicity team. Follow him on Twitter at http://twitter.com/russcontreras .

Please read our comment policy before commenting.