OPINION:

While the eyes of the political and media classes were on President Donald Trump as he commemorated the 75th anniversary of D-Day in the United Kingdom and in France last week, and then as we all watched for progress in the tariff war Mr. Trump started with Mexico, the Department of Justice was quietly trying to persuade a federal judge in Chicago to abandon first principles with respect to citizenship and sentencing.

The DOJ filed a motion asking a federal judge to strip the American citizenship of one Iyman Faris. Faris, who was born in Pakistan, has been a naturalized American citizen since 1994. In 2001, he pleaded guilty to conspiring to blow up the Brooklyn Bridge and was sentenced to 20 years in federal prison. His fellow “conspirators” were FBI agents pretending to be foreign and domestic terrorists willing to work with him.

In other words, there was no real conspiracy. Yet, federal prosecutors persuaded Faris and his lawyers that if the surveillance tapes the FBI made of Faris were shown to a jury, they would likely help produce a guilty verdict.

Faris’ case was one of many in the months immediately following the tragedy of 9/11 in which federal agents found vulnerable loners in the United States with Middle Eastern-sounding last names and seduced them into nonexistent plots. Stated differently, the feds created false crimes and then solved them.

If you believe — as Anglo-American jurisprudence taught for 600 years — that crime is harm, then Faris, who caused no harm, is no criminal. He is the victim of similar FBI tactics as those used on candidate Trump in 2015 and 2016.

If you believe that articulating thoughts about committing a crime, thoughts generated by FBI agents who tricked him into believing that they shared those thoughts — as modern-day Anglo-American jurisprudence teaches is criminal — then Faris is guilty of conspiracy to commit acts of terror.

I have argued for years that the government ought not to be in the business of creating crime just to get those it hates and fears off the street. My argument has occasionally received some resonance, but the government continues on this perilous path. Nevertheless, 18 years after Faris’ guilty plea, we are beyond the issue of whether Faris is actually guilty of a crime. We are now confronted with the unthinkable issue of whether he can be punished for a crime that has not yet occurred.

Faris’ 20-year sentence is now nearly complete, since today one ordinarily serves 85 percent of one’s incarceration in the federal system. Yet, the same feds who concocted his so-called crime have now argued to a federal judge that Faris should be stripped of his American citizenship and deported or — worse yet — kept in prison indefinitely, even though he will soon have served his full sentence.

Can the government get away with this?

The short answer: No. The longer answer is that the Trump DOJ, which should be wary of the dangers of false crimes and cutting constitutional corners, has abandoned its professed fidelity to first principles.

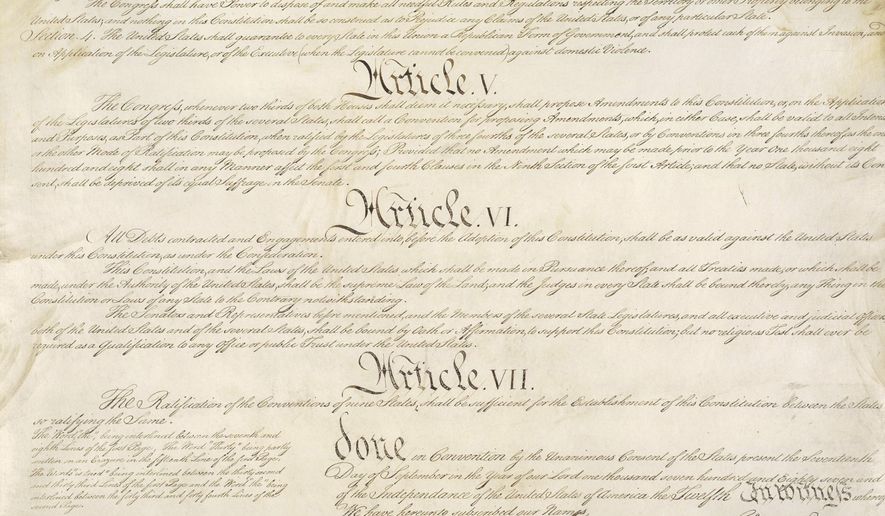

What are those principles? This is virgin and dangerous ground that the Trump administration seeks to walk upon. Under current law, one can only lose naturalized citizenship by either the voluntary, knowing, explicit and intentional renunciation of it or by the government proving the existence of knowing and intentional fraud perpetrated upon the government in order to obtain the citizenship.

These naturalized citizenship first principles were reinforced by the U.S. Supreme Court as recently as 2017, in a case the feds chose not to address when they made their application for stripping Faris of his citizenship or holding him beyond the duration of his sentence.

There is simply no statute that permits the removal of citizenship out of fear of future harm or for behavior that occurred after the citizenship was granted, and the DOJ knows that. Nor is there any statute that permits incarceration beyond the time sentenced once the sentence has been served. Congress could certainly provide by statute for the removal of citizenship and deportation of foreign-born persons convicted of certain crimes, but such provisions could only apply to crimes committed after Congress expressly provided for the punishments as penalties upon conviction.

As well, the government cannot ask a judge to enhance the penalty for a crime after the crime was committed, without violating due process. And the executive branch cannot on its own constitutionally enhance or threaten to enhance a penalty at any time or for any reason.

Under the doctrine of the separation of powers — which is integral to the U.S. Constitution — only Congress can prescribe penalties for violations of federal law, not the executive or judicial branches.

And under basic principles of due process in America, people are not punished because of what the government fears they might do. They may only be constitutionally punished for crimes for which they have lawfully been convicted — once real crimes, but in post-9/11 Orwellian America, regrettably, false crimes as well.

The United States was born as an act of violent political secession from Great Britain. That violence commenced in full after Thomas Jefferson articulated in the Declaration of Independence not only that our rights to due process are natural — he called them “inalienable” — but also that the colonists had had enough of being charged by the Crown for “pretended offenses” that were “foreign to our Constitution.”

The day we move to punish people — citizens or not — because of what the government fears they might do is the day all liberty will be lost. And the day the government punishes not in accordance with the law is the day for abolishing the government.

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.