OPINION:

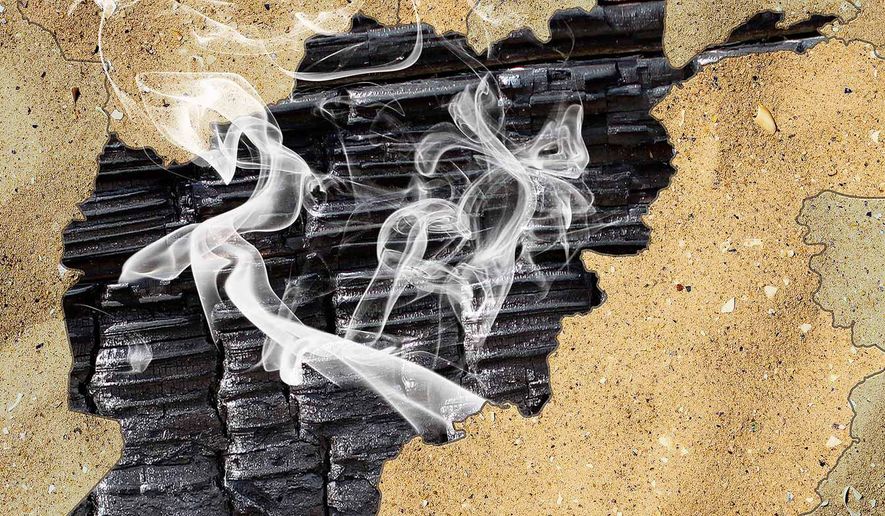

Arecent international study finds that Afghanistan is the world’s most insecure country. What has gone wrong?

After Soviet forces quit Afghanistan in February 1989, and the Mujahedin toppled the Afghan Communist regime in 1992, Washington was in a hurry to forget war-shattered Afghanistan. That policy of neglect and abandonment of a Cold War ally was the harbinger of other policy mistakes which have led to America’s complete failure in Afghanistan.

The success of this Cold War proxy confrontation was historically significant. It accelerated the Soviet Union’s collapse and freed Eastern Europe from Communist rule.

For the Afghans, the war ended in disaster. Once the country was theirs, most resistance leaders morphed into warlords and drug barons. Murder, rape, seizure of public and private property became the hallmark of their rule.

Disgusted with that medieval, ethnic amalgam, Washington didn’t care what transpired in that physically and financially broken country.

Then UNICAL, a Texas-based oil company, got interested in building a gas pipeline from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan and Pakistan to the Indian Ocean and lobbied Washington to help end Afghanistan’s civil war. Unwilling to re-engage with Afghanistan’s feudal leaders, America subcontracted the job to Pakistan. Pakistan’s secret service (ISI) had cooperated with the CIA during Afghanistan’s war of resistance against the Soviet Union. At the war’s end, Islamabad expected to see a Pakistan-friendly regime emerge in Kabul.

When Pakistan separated from India, Afghanistan refused to recognize the Duran Line, the border that had existed between India and Afghanistan and now separates Pakistan from Afghanistan. Hence, Pakistan worried about the possibility of having to fight a two-front war. Pakistan feared that — in the event of a combat with India, with which it has a disagreement over Kashmir — Afghanistan would attack it from the north. When Washington charged it to pacify Afghanistan, Islamabad realized the potential of installing in Kabul a Pakistan-subservient regime and eagerly seized the opportunity.

The Saudis, who fear Iran, were delighted to fund the enterprise, thereby to counterbalance Iran’s aggressive Shia fundamentalism with a Sunni fundamentalist regime on its eastern border.

ISI hired young Afghan men from the refugee camps, training them as fighters and future leaders for Afghanistan. Once the Taliban had overrun the resistance leaders’ chaotic reign, the Taliban’s inability to run the country guaranteed Islamabad full control over the Afghan government.

By then, Osama bin Laden crept around inside Afghanistan. Yet, Washington had had no policy for Taliban-ruled Afghanistan.

American politicians didn’t know that country and didn’t care to get to know it. They listened to the likes of Zalmay Khalilzad and the Karzais who either didn’t know better themselves or fed American policymakers with such nonsense as the Taliban have no support among the people. Give us 200 men, and we will kick them out of the country.

In their values and limited understanding of the outside world, the Taliban represented rural Afghanistan, where 80 percent of Afghans lives. Only, the Talibs (seminary students) had grown up in Pakistani refugee camps and attended Saudi-funded madrassas where they had been indoctrinated with the intolerant Wahhabi school of Islam.

The Taliban brought security to Afghanistan, something the Afghan people craved for. But by implementing strict Wahhabism, they hurled the country that already lived in the Middle Ages to some dark corner of human history for which I can’t find an equivalent.

Then, the tragedy of 9/11 burst into our hearts and minds, and America veered toward revenge. Bombing of Afghanistan began. CIA agents landed in that country’s north, carrying briefcases filled with $100 bills. In Bonn, Germany, an unruly conference was convened to form the post-Taliban government. Mr. Khalilzad was in the midst of it. He had become such a fixture in U.S. deliberations on Afghanistan that the German newspaper Die Frankfurter Allgemeine called him “President Bush’s Afghan.”

The congregation in Bonn was too disruptive for the international delegations to handle. The task of navigating the assembly fell to the Khalilzad-Karzai group. They knew how to control them with promises of American largesse or fury. Hamid Karzai was thrown to the top. The spoils were distributed among men with dirt and blood on their hands.

After Bonn, Messrs. Karzai and Khalilzad oversaw the return of warlords. The rule of law would not enter the Afghan people’s lives and America’s ultimate failure became inevitable.

• Nasir Shansab left his native Afghanistan in 1980 and became a U.S. citizen, advising the White House and Parliament on relations with his home country. Mr. Shansab’s latest book is “Silent Trees.” He maintains homes in suburban Washington, D.C. and Kabul.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.