OPINION:

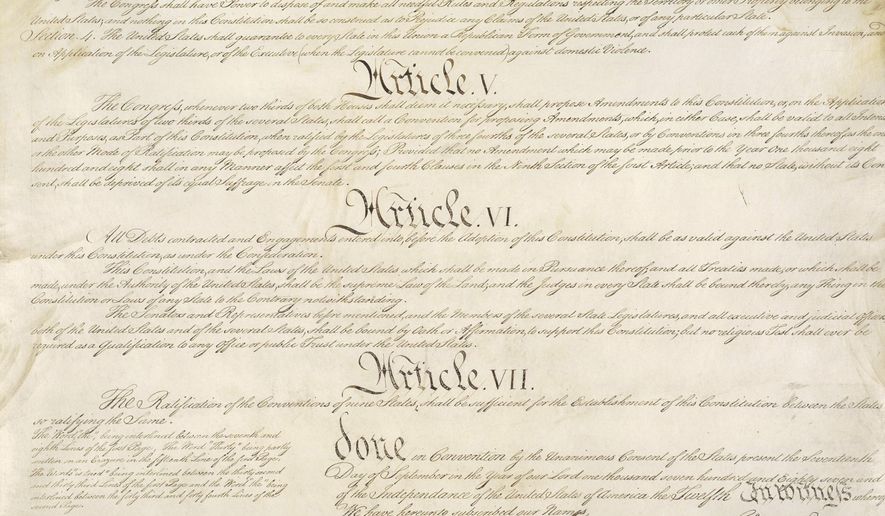

Late last month, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on a challenge to a question that the Commerce Department announced it would add to the 2020 census. The census itself has been mandated by the U.S. Constitution to be taken every 10 years so that representation in the House of Representatives could be fairly apportioned to reflect population changes.

Over the years, the folks who prepare the census developed an appetite for peering into the personal lives of everyone living in America, and Congress — which has the same mentality as the Census bureaucrats — permitted this. So, the Census Bureau began adding personal questions in the census itself.

The First, Fourth and Fifth Amendments constitutionally limit the only question that the census may ask, and the only question the recipient of the census must answer, to how many persons reside in the recipient’s dwelling. Yet, that constitutional question was not good enough for the bureaucrats. In addition to asking about bedrooms and toilets and education, this year, the Census folks were instructed by President Donald Trump to ask the citizenship status of all persons. The Supreme Court ruled that, on the justification offered by the Commerce Department, the question may not be asked.

Here is the backstory.

Though this has taken on serious political overtones, it is simply an issue about the government rejecting personal liberties — again. So, when the Census folks first revealed their intention to ask the citizenship question, two challenges were filed in different federal courts, and each sought to ascertain the reason for the question.

That’s because — even though the Constitution only mandates and only permits one question: “How many persons live here?” — federal law, in defiance of the Constitution, permits ancillary questions if the answers to those questions will assist the mission of the Census Bureau or the broader federal government. Thus, the lawsuits challenging the proposed citizenship question forced the federal government to explain how the answers received from this question would help the government to do its work. Both federal courts enjoined the printing of census forms until the feds explained themselves. When Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross refused to be interrogated at a deposition, a bureaucrat unfamiliar with the secretary’s and the president’s thinking came and testified. He told lawyers for the challengers and the Department of Justice that the feds needed citizenship data to enforce the Voting Rights Act.

All courts that examined that basis for the citizenship question — including the Supreme Court — disbelieved it. The Supreme Court characterized the stated reason as “contrived” and it directed the lower courts to keep their injunctions in place while they sought to determine the true motivations for the question.

When senior officials at the Commerce Department and the DOJ read the Supreme Court decision and examined the relevant law, they instructed the DOJ lawyers who were trying the cases to inform the judges in each case that the government recognized its defeat; the census would proceed without the citizenship question.

Then the president got involved and characterized what DOJ lawyers — his DOJ lawyers — told two federal judges as “fake news.” Then the DOJ pulled these career DOJ lawyers off the cases and sent in new teams of lawyers to try to come up with a lawful and credible reason to justify the citizenship question.

The Department of Justice is in a pickle on this because judges are always skeptical when lawyers — particularly government lawyers who needn’t worry about collecting a fee from a client — are replaced during a case with no rational explanation. It is far more likely that the career DOJ lawyers resigned from the cases — rather than reverse or contradict themselves — than it is that the DOJ brass removed them.

Can new DOJ trial teams salvage the DOJ’s cases? I don’t see how. The Commerce Department alleged that the reason for the census question was to assist in the enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. The Supreme Court declined to accept that explanation because the Voting Rights Act does not apply to three-quarters of the states and there was no request from the DOJ — which enforces the Voting Rights Act — asking for this. Moreover, federal courts uphold a doctrine that prohibits the government in a constitutional challenge from supplying reasons for its behavior as an afterthought — an after-the-fact rationalization. That doctrine will bar the judicial consideration of any reason that has not already been offered to support the citizenship question.

Compounding this is a statement that the president made last weekend; namely, that the citizenship question was being asked for reapportionment purposes. Hold on. That statement directly defies the consistent DOJ arguments that reapportionment has nothing to do with this.

Does the census count only citizens, citizens and lawfully resident noncitizens, or all persons? It counts all persons. Thus, citizenship is irrelevant to its counting mission and to the government’s enforcement of the Voting Rights Act, as noncitizens cannot vote.

Can the president rectify this with an executive order? In a word: No. The judicial injunctions against asking the question would apply to and supersede an executive order.

This mess is yet another example of personal liberty vs. government power. On one side is the right to privacy in the home, expressly guaranteed by the Fourth Amendment, and the right to silence, expressly guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment and by implication in the First Amendment. On the other side is an avaricious government that wants to know all it can about persons in America — whether constitutional or not.

Could a future Commerce Department ask how many guns are kept in the house or who living there goes to Mass on Sunday or if any resident has had an abortion? How much longer will a free people permit these intrusions? How much longer will we be a free people?

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.