OPINION:

When Donald Trump was looking for a catchy phrase during his 2016 presidential campaign to address the issue of immigrants entering the United States unlawfully — a line that would resonate with his supporters — he came up with the phrase “build the wall.” The reference, of course, is to what Mr. Trump advertised would be a 30-foot-tall, thousand-mile-long Mexico-financed physical wall along our border with Mexico.

At first, most folks seemed to dismiss this as pie in the sky. Why would the government of a foreign country pay for a wall in the United States built so as to keep its own citizens and residents from entering the United States? The answer: It wouldn’t.

So President Trump changed his argument that Mexico would pay directly for his wall by arguing instead that the $5.7 billion down payment he wants — on a $25 billion to $30 billion project — would indirectly pay for itself in reduced government welfare and law enforcement expenses. The idea of the wall never took hold during the first two years of his presidency, when the Republicans controlled both houses of Congress.

Even Republicans were leery of the cost and the imagery. The federal government is running about $1 trillion a year in the red, and Republicans are looking to offer comfort in their party to Hispanics. Adding to that debt to build a wall that would affront other Hispanics did not rest well with them. Until now.

Now that the Democrats control the House of Representatives, where the idea of a wall is dead on arrival, it is easier for House Republicans to argue in favor of it. Because the Democrats numerically outnumber them, the House Republicans won’t be forced to vote on it. The president is probably kicking himself for not calling in a few favors and addressing the wall before the Democrats took control of the House.

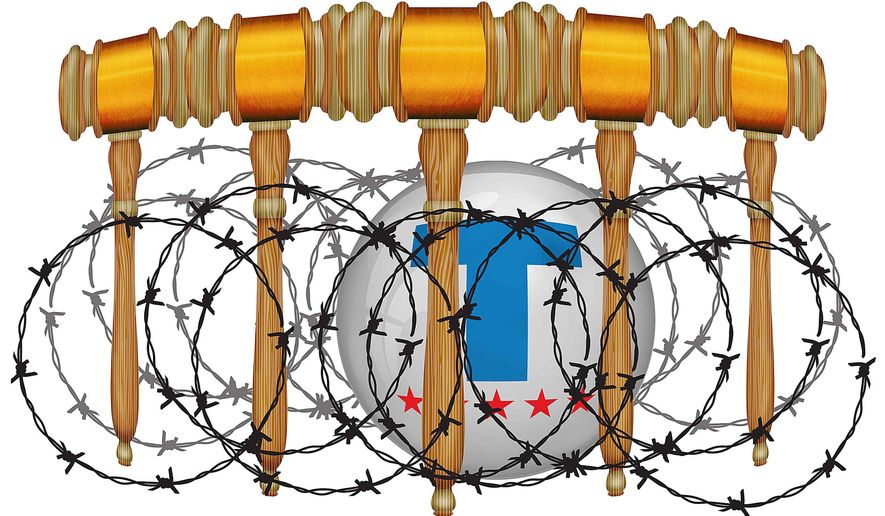

So, faced with intractable opposition in the House and only lukewarm, mainly symbolic support in the Senate, Mr. Trump has threatened to bypass Congress, declare a national state of emergency and build the wall on his own. Can he legally do this? In a word: No.

Here is the back story.

The U.S. Constitution is the supreme law of the land. Everyone who works in government takes a public oath of fidelity to the Constitution; that means to its very words and to the values that those words represent. All federal powers come from the Constitution — and from no other source. The states formed the federal government and limited its powers when they ratified the Constitution. These are all basic truisms of American government, yet we have veered so far from them that they bear repeating.

Now, back to the president’s wall. President Trump has no power to build a wall or a fence or a doghouse on private property without an express or implied congressional authorization to do so. The vast majority of the property in Texas on which he wants to build is private, according to Rep. Will Hurd, Texas Republican, whose district contains a longer stretch of the border than anyone else’s.

Thus, the federal government must use eminent domain, which gives each landowner the right to a trial to challenge the government as to the worth of the property the government wants. Rep. Hurd, a former CIA agent and conservative Republican who opposes the wall, has articulated the views of most of his 800,000 constituents: Not in my backyard.

We know from the plain wording of the Constitution and from history that all expenditures of money from the federal treasury and all federal use of private property must first be approved by Congress. In 1952, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on this when President Harry Truman seized American steel mills during a labor strike and directed the secretary of Commerce to hire folks to operate the mills, pursuant to his own emergency declaration that steel was vital to the war effort in Korea. The court held that only Congress could authorize the seizure or adverse government occupancy of private property and the expenditure of money needed to operate the mills.

Then, in 1976, Congress provided a definition— which, shortly thereafter, the courts refined — of a national emergency: The existence of events truly beyond the ordinary, wherein there is a palpable and immediate threat to lives, safety or property that cannot be addressed by the employment of ordinary government assets or the exercise of ordinary governmental powers. That is hardly the case today with the former Central American caravan in Mexico now settled in and housed by the Mexican government away from the border.

Nevertheless, the 1976 law requires that all ordinary assets — our president prefers the military — be determined useless before a lawful emergency can come into effect. The military useless in an emergency? And if this is such an emergency, why did the president wait until it abated before addressing it?

Perhaps the answer is that his frustration with the Democratic House has reached a boiling point, but that boiling point cannot be a basis for a declaration of a national emergency. A valid emergency declaration streamlines the government to address the emergency, but it cannot authorize anything that the Constitution prohibits, nor can it authorize the president to avoid anything that the Constitution requires.

The president has sworn not only fidelity to the Constitution but also to take care that federal laws be enforced. If he could disregard that oath, if he could ignore those laws, if he could spend money not authorized by Congress, if he could occupy private property not subject to eminent domain against the will of the owners — in short, if he could make the laws, as well as enforce them, then he would not be a president. He’d be a monarch.

• Andrew P. Napolitano, a former judge of the Superior Court of New Jersey, is a regular contributor to The Washington Times. He is the author of nine books on the U.S. Constitution.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.