OPINION:

Thanks in part to higher regulatory barriers erected by the Trump administration and Congress, Chinese bids to acquire American companies either in whole or in part — especially those possessing defense-related technology — were down sharply last year.

But many transactions still keep getting approved, and significant opportunities remain for Chinese individuals and entities to buy into the American economy, largely because even administration officials and congressional supporters of tighter limits take an overly narrow view of the threats posed by even the most seemingly innocuous transactions. Nor is it clear whether Washington will seriously monitor whether the conditions attached to many such foreign direct investment approvals are being respected.

American leaders can dramatically reduce these threats and uncertainties, and in one fell swoop — by banning such Chinese direct investment (in hard assets, as opposed to Treasury debt) outright.

U.S. concerns about Chinese investors taking over or even acquiring minority stakes in American businesses and properties have naturally, and rightly, focused on national security. In this vein, it’s especially encouraging that American policy now recognizes that the range of U.S. technologies, industries and holdings that China could exploit to America’s detriment is considerably wider than previously thought.

But ever since China began targeting American assets, the purely economic dangers have been downplayed. In fact, Chinese investments in sectors like consumer goods, and even in capital-intensive manufacturing that seems entirely civilian in nature, have been touted as crucial economic boons. Consequently, politicians around the country have courted the Chinese as valuable new job creators and tax-base pillars.

The problem, though, is that any such investment from China inevitably undermines free market competition — which is supposed to be the key to the nation’s historic success and current prosperity. The reason? Chinese investors benefit from all the interventionist practices (including subsidies) that define the Chinese economic system. As a result, they bring to the American business scene advantages that non-Chinese businesses don’t enjoy. How can this inequitable situation produce the gains — notably, superior product quality and continuing innovation — brought by genuine free market competition?

It’s true that many of these Chinese entities are considered private companies. Yet even leaving aside the accuracy of this label for a country where government’s heavy hand directly influences nearly everything bearing on commercial success, it’s clear that any Chinese investor large enough to mull an overseas footprint has no choice but to advance Beijing’s agenda whenever so ordered.

Nor is there any inherent reason, as claimed by many supporters of foreign direct investment in the United States, that banning Chinese investment will result in banning U.S. hard asset purchases from other countries.

For China can easily be placed into a category all its own — and in ways entirely consistent with international laws against non-discrimination. After all, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has permitted its members, including the United States, to classify China as a non-market economy — that is, one in which the government “has a complete or substantially complete monopoly of its trade and where all domestic prices are fixed by the State.”

China isn’t alone on this U.S. trade list, but the others (except for Vietnam) are such global trade midgets that it’s clear that Washington is unlikely to abuse this right on the foreign investment front. Also noteworthy: The United States has taken several countries out of this category over the years — including Russia, in 2002.

The other leading objections to a China investment ban are no more compelling. If the prospective American recipients of Chinese resources have promising business models, other investors will surely find them. Moreover, although all Chinese investments pose free-market distortion risks, their absolute scale has remained modest. So the U.S. economy can easily do without them.

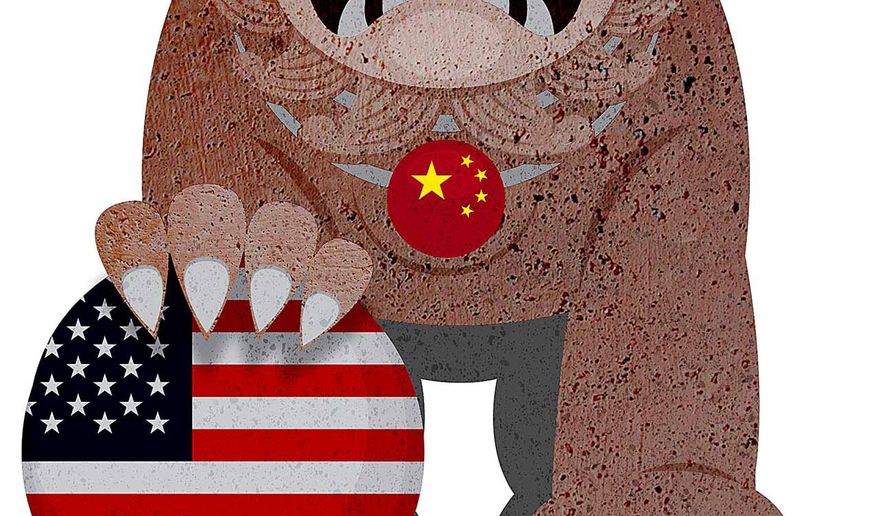

Yes, China could retaliate against American companies if Washington shut out its investors, but Beijing is already making life miserable for many U.S. and other foreign companies operating in the PRC. And the rest face a grim future, as China clearly intends to chew up foreign partners and spit them out once they’re no longer needed.

Moreover, way too much American corporate investment in China has backfired badly against American interests — either decimating domestic U.S. competitors via subsidy-aided exports or transferring defense-related know-how to Chinese partners either voluntarily or under duress. So America could actually reap benefits from a smaller business footprint in China.

The United States faces a clear choice on China investment policy. It can keep tying itself up in knots — and wasting valuable time and resources in the process — trying to figure out case-by-case which Chinese enterprises and individuals are relatively harmless and which are truly dangerous, which are reasonably private and which are not. Or it can keep it simple, stop playing this mug’s game, and ban all investment from the PRC until genuine free market Chinese reform is a reality, not a pipe dream.

• Alan Tonelson, founder of RealityChek, a public policy blog focusing on economics and national security, is the author of “The Race to the Bottom” (Westview Press, 2002).

Please read our comment policy before commenting.