OPINION:

U.S. foreign policy hands are concerned that President Trump’s withdrawal from Syria is likely to encourage Turkey to prosecute a military campaign against the Kurds. Many fear that abandoning a partner in the campaign against the Islamic State will show that America does not stand by its allies.

Mr. Trump has vowed to protect the Kurds, warning Turkey that he will destroy its economy should it lay siege to them. Hence, Washington and Ankara are trying to work out details of a buffer zone separating Kurdish and Turkish forces.

However, short of a permanent deployment, there is little the United States can do to shelter the Kurds long-term, never mind ensure an independent Kurdish state in northern Syria. That the Kurds will now turn toward other powers — like Iran and Russia — is a natural fact of history and geography, i.e. geopolitics.

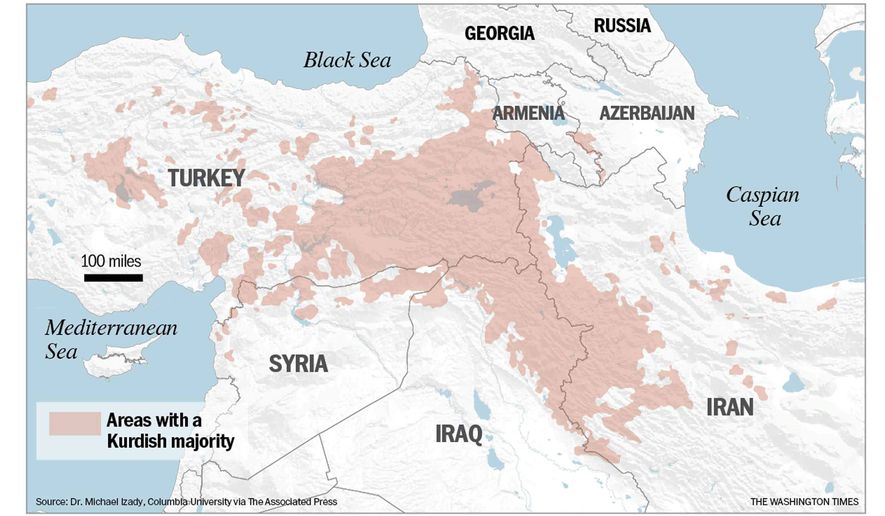

Even analysts and journalists appear to be confused about the Kurds — including the nomenclature used to describe them. The Kurds are a Middle Eastern minority spread out from Syria in the West, through Turkey and Iraq, to Iran in the east, and further divided into various political groupings.

But this is not what the foreign policy establishment is referring to in the Syria debate. Rather, they are talking about a specific Kurdish political institution in northern Syria, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), and its military wing, the People’s Protection Units (YPG). This is the Syrian franchise of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been at war with Turkey for 35 years, and is a U.S.-designated terrorist group inspired by Marxist doctrine.

How the United States came to ally with such an organization in the first place was a function of Barack Obama’s grand strategy for the Middle East — to realign U.S. interests with Iran.

Mr. Obama never wanted to intervene in Syria, fearing that it might jeopardize his blossoming relationship with Iran, patron of Syrian president Bashar Assad. But the White House felt pressured to step in after ISIS murdered American journalists. The trick was to avoid turning the intervention against ISIS into an instrument that would help anti-Assad rebels and Turkey.

“The PKK was the perfect partner for the Obama White House,” says Tony Badran, senior fellow at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies. “Not only were they not interested in pursuing an anti-Assad agenda but they would also create an irritant for Turkey that would distract or even block Ankara from fighting Assad.”

Mr. Obama’s military alliance with the PKK naturally angered then-Prime Minister and now President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. The group presents Ankara with its most vital national security concern, threatening Turkish peace at home, and is hence Mr. Erdogan’s greatest political liability.

Mr. Erdogan initiated a peace process with the PKK as early as 2012, which was stalled in part by the 2014 U.S. intervention. With the White House at its back, the PKK was convinced it had enough leverage to walk away from peace talks to acquire more, by carving out territory in northern Syria — with American support. Mr. Erdogan is a difficult U.S. ally, distrusted by both Democrats and Republicans. However, the idea that Washington should swap out a NATO member and replace it with the PKK is strategically wanton.

In spite of the PKK’s proven military abilities, it is no substitute for a nation-state with an army, an important air base at Incirlik, and naval bases on major waterways. As Mr. Trump’s Syria envoy James Jeffrey recently said, “the United States does not have permanent relationships with substate entities.”

Sympathetic Westerners believe that the PKK in Syria deserves a state. But merit does not factor into geopolitics: You have a state if you can keep it.

A map shows why that is unlikely. The Syrian PKK is land-locked, with Assad regime forces to the west, Sunni Arabs to the south, Turkey to the north, and to its east another Kurdish party in Iraq that is hostile to them, the Kurdistan Democratic Party, a longstanding U.S. ally with Turkish ties.

Kurdish politics are historically shaped by the fact of the two regional powers, Turkey and Iran, from whom they must chose a patron. As a Turkish PKK adviser once put it: “Iran influences the PKK because the PKK is based on the Iranian border. When you fight a party, you have to find support from some other party.”

Unless the PKK comes to its senses and reaches an American-brokered compromise with Turkey that satisfies the latter’s national security interests, it has no choice but to partner with Iran and its axis, which now includes Russia. The United States’ temporary alliance with the PKK only delayed the inevitable.

As it is, the United States empowered the PKK beyond its wildest imagination. By funding, training and arming a substate actor, Washington made the PKK the envy of substate actors the world over. Any of which would welcome the same munificence, even though they know, as the PKK did, that the United States will someday return home, far over the horizon.

Now that Mr. Trump has decided it is time to leave, the PKK, grateful to the United States for having buttressed its negotiating position, would be wise to re-initiate peace talks with Turkey.

• Lee Smith is the author of “The Strong Horse: Power, Politics, and the Clash of Arab Civilizations.”

Please read our comment policy before commenting.